CHAPTER 5

.NET MAUI Common Controls

.NET MAUI ships with a rich set of common controls that you can use to build cross-platform user interfaces easily, and without the need for the complexity of platform-specific features. As you can imagine, the benefit of these common controls is that they run on Android, iOS, Mac Catalyst, Tizen, and Windows from the same codebase.

In this chapter, you’ll learn about common controls, their properties, and their events. Other controls will be introduced in Chapter 7, especially controls whose purpose is displaying lists of data.

Using the companion code

In order to follow the examples in this chapter, either create a brand-new .NET MAUI solution (the name is up to you) or open the solution in the Chapter5_CommonControls folder of the companion code repository.

If you choose the first option, every time a new control is discussed, just clean the content of the root ContentPage object in the XAML file and remove any C# code specific to a single control. As an alternative, you can add a new item of type .NET MAUI ContentPage to the project and make your edits here.

If you instead want to use the companion solution directly, every time a view is discussed, uncomment the related code in the MainPage.xaml file (and in its code-behind where necessary).

Understanding the concept of view

In .NET MAUI, a view is the building block of any mobile application. A view represents what you would call a widget in Android, a view in iOS, and a control in Windows. Views derive from the Microsoft.Maui.Controls.View class.

The MAUI documentation groups layouts, views, and pages under the name of controls, so from the terminology perspective of MAUI, you need to remember this:

· A control can be a layout, page, or view.

· A layout is a container for other visual elements.

· A view is a component that allows interaction with the device and system features.

· Pages represent the organizational hierarchy of the application.

Layouts are views themselves and derive from Layout, an intermediate object in the hierarchy that derives from View and includes a Children property, allowing you to add multiple visual elements to the layout itself. From now on, I will be using view and control interchangeably, but remember that documentation and tutorials often refer to views.

Views’ common properties

Views share several properties that are important for you to know in advance. These are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4: Views’ common properties

Property | Description |

|---|---|

HorizontalOptions | Same as Table 2. |

VerticalOptions | Same as Table 2. |

HeightRequest | Of type double, gets or sets the height of a view. |

WidthRequest | Of type double, gets or sets the width of a view. |

IsVisible | Of type bool, determines whether a control is visible on the user interface. |

IsEnabled | Of type bool, allows enabling or disabling a control, keeping it visible on the UI. |

GestureRecognizers | A collection of GestureRecognizer objects that enable touch gestures on controls that do not directly support touch. These will be discussed later in this chapter. |

Tip: Controls also expose the Margin property described in Table 3.

If you wish to change the width or height of a view, remember that you need the WidthRequest and HeightRequest properties, instead of Height and Width, which are read-only and return the current height and width.

Introducing common views

This section provides a high-level overview of .NET MAUI’s common views and their most utilized properties. Remember to add the official documentation about the user interface to your bookmarks for a more detailed reference.

User input with the Button

The Button control is certainly one of the most-used controls in every user interface. You already saw a couple examples of the Button previously, but here is a quick summary. This control exposes the properties summarized in Table 5, and you declare it like this:

<Button x:Name="Button1" Text="Tap here" TextColor="Orange" BorderColor="Red"

BorderWidth="2" CornerRadius="2" Clicked="Button1_Clicked"/>

Table 5: Button properties

Property | Description |

|---|---|

Text | The text in the button. |

TextColor | The color of the text in the button. |

BorderColor | Draws a colored border around the button. |

BorderWidth | The width of the border around the button. |

CornerRadius | The radius of the edges around the button. |

ImageSource | An optional image to be set near the text. |

Notice how you can specify a name with x:Name so that you can interact with the button in C#, which is the case when you set the Clicked event with a handler. This control also exposes the FontSize, FontFamily, and FontAttributes properties, whose behavior is discussed in the next section about text.

Introducing the ImageButton

.NET MAUI gives you the option to use the ImageButton view when you want to display an image instead of text. Its difference from the Button is that this one can display both text and a small icon by assigning both the Text and ImageSource properties. The ImageButton can only show an image.

Working with text: Label, Entry, and Editor

Displaying text and requesting input from the user in the form of text is extremely common in mobile apps. .NET MAUI, like Xamarin.Forms, offers the Label control to display read-only text, and the Entry and Editor controls to receive text. The Label control has some useful properties, as shown in the following XAML:

<Label Text="Displaying some text" LineBreakMode="WordWrap"

TextColor="Blue" HorizontalTextAlignment="Center"

VerticalTextAlignment="Center"/>

LineBreakMode allows you to truncate or wrap a long string, and can be assigned a value from the LineBreakMode enumeration. For example, WordWrap splits a long string into multiple lines proportionate to the available space. If not specified, NoWrap is the default.

HorizontalAlignment and VerticalAlignment specify the horizontal and vertical alignment for the text. The Entry control instead allows you to enter a single line of text, and you declare it as follows:

<Entry x:Name="Entry1" Placeholder="Enter some text..."

TextColor="Green" Keyboard="Chat" Completed="Entry1_Completed"/>

The Placeholder property lets you display specific text in the entry until the user types something. It is useful for explaining the purpose of the text box. When the user taps the Entry, the on-screen keyboard is displayed.

The appearance of the keyboard can be controlled via the Keyboard property, which allows you to display the most appropriate keys, depending on the Entry’s purpose. Supported values are Chat, Email, Numeric, Telephone, and Number. If Keyboard is not assigned, Default is assumed.

Additionally, Entry exposes the MaxLength property that allows you to set the max length of the text the user can enter. This control also exposes two events: Completed, which is fired when the users finalize the text by tapping the Return key, and TextChanged, which is fired at every keystroke.

You provide event handlers the usual way, as follows:

private void Entry1_Completed(object sender, EventArgs e)

{

// Entry1.Text contains the full text

}

Entry also provides the IsPassword property to mask the Entry’s content, which you use when the user must enter a password. Another very useful property is ReturnType, whose value is of type ReturnType enumeration, which allows you to specify the text to be displayed in the Enter key of the keyboard. Possible values are Done, Go, Next, Search, Send, and Default (which sets the default text for each platform).

The combination of the Label and Entry controls is visible in Figure 30.

Figure 30: Label and Entry controls

The Editor control is very similar to Entry in terms of behavior, events, and properties, but it allows for entering multiple lines of text. For example, if you place the editor inside a layout, you can set its HorizontalOptions and VerticalOptions properties with Fill so that it will take all the available space in the parent. Both the Entry and Editor views expose the IsSpellCheckedEnabled property, which enables spell check over the entered text.

Formatted strings and bindable spans

The Label control exposes the FormattedText property, which can be used to implement more sophisticated string formatting. This property is of type FormattedString, an object that is populated with a collection of Span objects, each representing a part of the formatted string. The following snippet provides an example:

<Label

HorizontalOptions="Center"

VerticalOptions="Center">

<Label.FormattedText>

<FormattedString>

<FormattedString.Spans>

<Span FontSize="Large" FontAttributes="Bold"

TextColor="Red"

Text=".NET MAUI Succinctly" />

<Span FontSize="Medium" FontAttributes="Italic"

TextColor="Black" Text="3rd edition" />

<Span FontSize="Small" FontAttributes="Bold"

TextColor="Blue"

Text="by Alessandro Del Sole" />

</FormattedString.Spans>

</FormattedString>

</Label.FormattedText>

</Label>

You can basically use Span objects to format specific paragraphs or sentences by setting most of the properties already exposed by the Label control, such as Text, Font, FontFamily, FontSize, FontAttributes, TextColor, and BackgroundColor.

Tip: In Xamarin.Forms, coloring text in a Span was accomplished via the ForegroundColor property.

Managing fonts

Controls that display some text (including the Button) or wait for user input through the keyboard also expose some properties related to fonts, such as FontFamily, FontAttributes, and FontSize.

FontFamily specifies the name of the font you want to use. FontAttributes displays text as Italic or Bold and, if not specified, None is assumed. With FontSize, you can specify the font size with either a numeric value or with a so-called named size, based on the Body, Caption, Header, SubTitle, Title, Micro, Small, Medium, and Large values from the NamedSize enumeration.

With this enumeration, .NET MAUI chooses the appropriate size for the current platform. For instance, the following two options are allowed to set the font size:

<Label Text="Some text" FontSize="72"/>

<Label Text="Some text" FontSize="Large"/>

Unless you are writing an app for a single platform, it is recommended that you avoid using numeric values—use the named size instead. You can also manage the spacing between individual characters in a string by setting the CharacterSpacing property, of type double, whose default value is zero.

Another useful property is TextTransform, which you can use to automatically convert a string into uppercase or lowercase. Allowed values are Uppercase, Lowercase, Default, and None. By default, strings are not transformed. It is also possible to apply underline and strikethrough decorations to a string by assigning the TextDecorations property with Underline and Strikethrough (the default is None).

Using custom fonts

A common requirement with modern apps is to use custom fonts. These can be available through official design channels, such as Google Material, or produced by professional designers. .NET MAUI supports both .ttf and .otf file formats.

In order to use custom fonts, follow these steps:

- Add the .ttf or .otf files into the Resources\Fonts subfolder of the project.

- Set the Build Action property of each file to MauiFont.

- Assign the FontFamily property of your view with the name of the font as follows:

<Label Text="Some text" FontFamily="MyFont.ttf"/>

- Register the font with the app. This is accomplished in the MauiProgram.cs file. When you create a new project, two fonts are also registered so you have the following reference:

var builder = MauiApp.CreateBuilder();

builder

.UseMauiApp<App>()

.ConfigureFonts(fonts =>

{

fonts.AddFont("OpenSans-Regular.ttf", "OpenSansRegular");

fonts.AddFont("OpenSans-Semibold.ttf", "OpenSansSemibold");

});

In summary, for each custom font, you invoke the AddFont method, passing the file name and the friendly name. This method works over an IFontCollection object returned by the ConfigureFonts extension method, and is assigned to the instance of the MauiAppBuilder class, an object that represents the running instance of the app.

If you worked with custom fonts in Xamarin.Forms, you know how simpler the MAUI approach is, because you only need to copy font files to one folder and assign properties just once.

Working with dates and time: DatePicker and TimePicker

Another common requirement in mobile apps is working with dates and time: .NET MAUI provides the DatePicker and TimePicker views for that. On each platform, these are rendered with the corresponding date and time selectors.

DatePicker exposes the Date, MinimumDate, and MaximumDate properties that represent the selected or current date, the minimum date, and the maximum date, respectively, all of type DateTime. It exposes an event called DateSelected, which is raised when the user selects a date. You can handle this to retrieve the value of the Date property. The view can be declared as follows:

<DatePicker x:Name="DatePicker1" MinimumDate="07/17/2021"

MaximumDate="06/30/2022"

DateSelected="DatePicker1_DateSelected"/>

Tip: Properties of type DateTime are immediately validated in the XAML editor. If you enter an invalid date, a red squiggle will appear under the date.

Then in the code-behind, you can retrieve the selected date like this:

private void DatePicker1_DateSelected(object sender, DateChangedEventArgs e)

{

DateTime selectedDate = e.NewDate;

}

The DateChangedEventArgs object stores the selected date in the NewDate property and the previous date in the OldDate property. Figure 31 shows the DatePicker in action.

Figure 31: The DatePicker in action

The TimePicker exposes a property called Time, of type TimeSpan, but it does not expose a specific event for time selection, so you need to use the PropertyChanged event. In terms of XAML, you declare a TimePicker like this:

<TimePicker x:Name="TimePicker1"

PropertyChanged="TimePicker1_PropertyChanged"/>

Then, in the code-behind, you need to detect changes on the Time property as follows:

private void TimePicker1_PropertyChanged(object sender,

System.ComponentModel.PropertyChangedEventArgs e)

{

if (e.PropertyName == TimePicker.TimeProperty.PropertyName)

{

TimeSpan selectedTime = TimePicker1.Time;

}

}

TimeProperty is a dependency property, a concept that will be discussed in Chapter 7. Figure 32 shows the TimePicker in action.

Figure 32: The TimePicker in action

Tip: You can also assign a date or time to pickers in the C# code-behind. For example, one can be assigned in the constructor of the page that declares them.

Displaying HTML contents with WebView

The WebView control allows for displaying HTML content, including webpages and static HTML markup. This control exposes the Navigating and Navigated events that are raised when navigation starts and completes, respectively.

The real power is in its Source property, of type WebViewSource, which can be assigned with a variety of content, such as URIs or strings containing HTML markup. For example, the following XAML opens the specified website:

<WebView x:Name="WebView1" Source="https://www.microsoft.com"/>

The following example shows how you can assign the Source property with a string:

WebView1.Source = "<div><h1>Header</h1></div>";

For dynamic sizing, a better option is enclosing the WebView inside a Grid layout. If you instead use one of the stack layouts, you need to supply height and width explicitly. Figure 33 shows how the WebView appears.

Figure 33: Displaying HTML content with WebView

If the webpage you display allows you to browse other pages, you can leverage the built-in GoBack and GoForward methods, together with the CanGoBack and CanGoForward Boolean properties, to programmatically control navigation between webpages.

Tips about the BlazorWebView

.NET MAUI exposes a useful control called BlazorWebView, which allows for hosting Blazor applications inside a MAUI project. In addition, Visual Studio 2022 includes a project template called .NET MAUI Blazor App that generates a project ready to host Blazor contents.

Using this control assumes you have built applications with Blazor, which cannot be taken for granted in this book. For this reason, here you are informed about the existence of this view, and you can refer to the Microsoft documentation for further information.

Implementing value selection

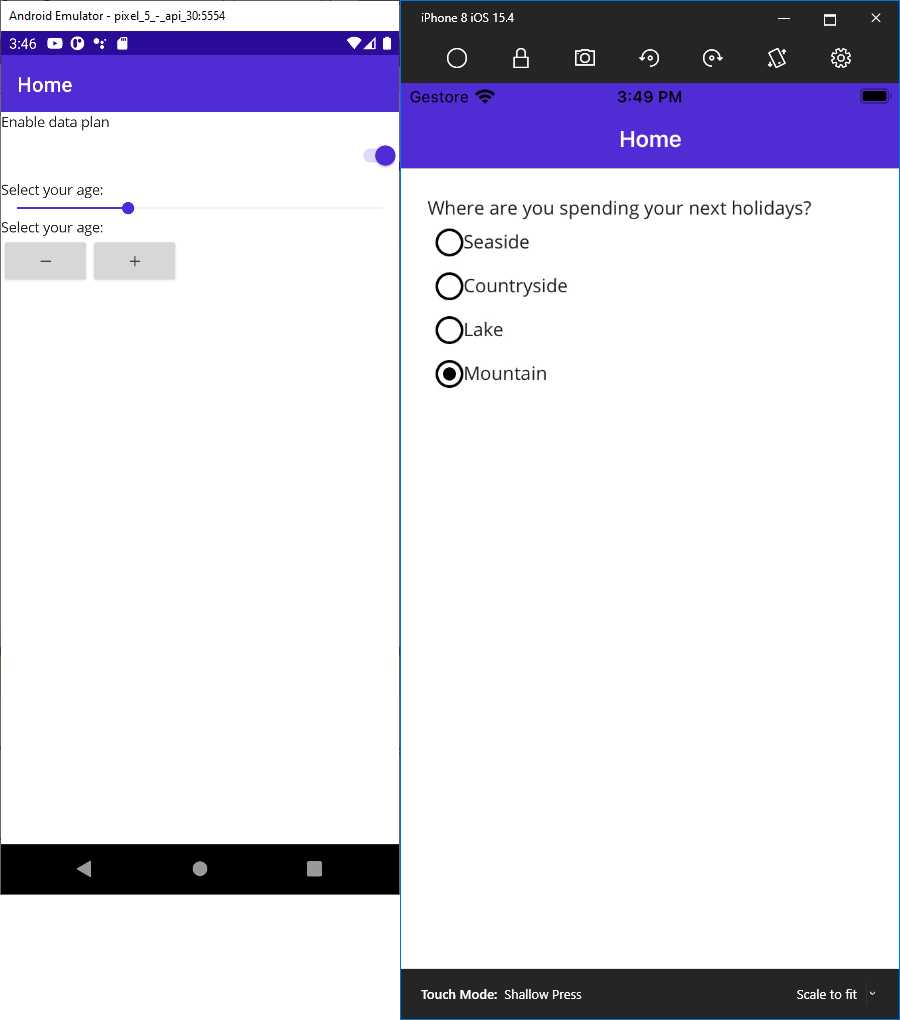

.NET MAUI offers a number of controls for user input based on selecting values. More specifically, the views provided for this purpose are the Switch, CheckBox, RadioButton, Slider, and Stepper, discussed in the next paragraphs.

On/off value selection with the Switch

The first of them is Switch, which provides a toggled value and is useful for selecting values such as true or false, on or off, and enabled or disabled. It exposes the IsToggled property, which turns the switch on when true, and the Toggled event, which is raised when the user changes the switch position.

This control has no built-in label, so you need to use it in conjunction with a Label as follows:

<StackLayout Orientation="Horizontal">

<Label Text="Enable data plan"/>

<Switch x:Name="Switch1" IsToggled="True" Toggled="Switch1_Toggled"

Margin="5,0,0,0"/>

</StackLayout>

The Toggled event stores the new value in the ToggledEventArgs object that you use as follows:

private void Switch1_Toggled(object sender, ToggledEventArgs e)

{

bool isToggled = e.Value;

}

You can also change the color for the selector when it’s turned on, assigning the OnColor property with the color of your choice.

True/false selection with the CheckBox

The CheckBox is a special view that allows for selecting a true or false value via a flag. The following code demonstrates how to implement a CheckBox:

<CheckBox x:Name="CheckBox1" IsChecked="True"

CheckedChanged="CheckBox1_CheckedChanged"/>

The IsChecked property represents the true or false selection. The CheckedChanged event is fired when the user changes the value of the control. The selected value is sent via an instance of the CheckedChangedEventArgs class as follows:

private void CheckBox1_CheckedChanged(object sender, CheckedChangedEventArgs e)

{

bool selectedValue = e.Value;

}

The CheckBox is really effective on desktop systems, whereas on mobile applications a better choice in terms of user experience could be the Switch. Your graphic designer will help you choose the best view to fit your requirements.

Numeric value selection with the Slider

Slider allows the selection of a value from a linear range. It exposes the Value, Minimum, and Maximum properties, all of type double, which represent the current value, minimum value, and maximum value. Like Switch, it does not have a built-in label, so you can use it together with a Label as follows:

<StackLayout Orientation="Horizontal">

<Label Text="Select your age: "/>

<Slider x:Name="Slider1" Maximum="99" Minimum="13" Value="30"

ValueChanged="Slider1_ValueChanged"/>

</StackLayout>

The ValueChanged event is raised when the user moves the selector on the Slider, and the new value is sent to the NewValue property of the ValueChangedEventArgs object you get in the event handler.

Progressive selection with the Stepper

The last control is the Stepper, which allows the supply of discrete values with a specified increment. It also allows the specification of minimum and maximum values. You use the Value, Increment, Minimum, and Maximum properties of type double as follows:

<StackLayout Orientation="Horizontal">

<Label Text="Select your age: "/>

<Stepper x:Name="Stepper1" Increment="1" Maximum="85" Minimum="13"

Value="30" ValueChanged="Stepper1_ValueChanged"/>

<Label x:Name="StepperValue"/>

</StackLayout>

Notice that both Stepper and Slider only provide a way to increment and decrement a value, so it is your responsibility to display the current value, for example, with a Label that you can handle through the ValueChanged event. The following code demonstrates how to accomplish this with the Stepper:

private void Stepper1_ValueChanged(object sender, ValueChangedEventArgs e)

{

StepperValue.Text = e.NewValue.ToString();

}

Figure 34 shows all the aforementioned views.

Figure 34: A summary view of the Switch, Slider, and Stepper controls

Item selection with the RadioButton

The RadioButton control allows for implementing mutually exclusive item selection. This means that if you have multiple options, only one will be accepted. Consider the following example:

<VerticalStackLayout>

<Label Text="Where are you spending your next holidays?"/>

<RadioButton Content="Seaside" GroupName="HolidayOptions" />

<RadioButton Content="Countryside" GroupName="HolidayOptions"/>

<RadioButton Content="Lake" GroupName="HolidayOptions"/>

<RadioButton Content="Mountain" GroupName="HolidayOptions"/>

</VerticalStackLayout>

This allows for selecting one of the proposed values. The Content property is of type IView, which means that you are not limited to displaying strings, but you can display complex visual hierarchies (for example, images and text).

The GroupName property is not mandatory, but it is necessary to make radio buttons mutually exclusive to one another. All the buttons to which the property is assigned will be considered part of the same group. There is a simpler syntax based on attached properties that works as shown in the following code:

<VerticalStackLayout RadioButtonGroup.GroupName="HolidayOptions">

<Label Text="Where are you spending your next holidays?"/>

<RadioButton Content="Seaside" />

<RadioButton Content="Countryside" />

<RadioButton Content="Lake" />

<RadioButton Content="Mountain" />

</VerticalStackLayout>

If you specify the RadioButtonGroup.GroupName attached property at the layout level, all the nested RadioButton controls will be considered part of the same group. Figure 35 shows the result of this code.

Figure 35: Item selection with RadioButton views

In the following code, you can see how to provide a complex object as the content:

<VerticalStackLayout Margin="20"

RadioButtonGroup.GroupName="HolidayOptions">

<Label Text="Where are you spending your next holidays?"/>

<RadioButton Value="seaside">

<RadioButton.Content>

<HorizontalStackLayout>

<Image Source="seaside.jpg"/>

<Label Text="Seaside" />

</HorizontalStackLayout>

</RadioButton.Content>

</RadioButton>

…

</VerticalStackLayout>

Especially with data-binding scenarios (such as those you will learn about in Chapter 7), it is good to assign a value to the control instead of relying on the displayed content. You can accomplish this by assigning the Value property. To handle user interactions, the RadioButton exposes the CheckedChanged event, which is fired when the status changes, and that you handle as follows:

void RadioButton_CheckedChanged(object sender, CheckedChangedEventArgs e)

{

// Perform required operation

}

Put succinctly, the Value property, of type bool, is true when the RadioButton is selected and false when it is unselected. The same value is also stored inside the IsChecked property. The latter can be used to both read and programmatically set the value for each RadioButton.

Tip: The RadioButton supports control template redefinition and visual states. This is out of scope here, but you can find further information in the documentation.

Introducing the SearchBar

The SearchBar is a very useful view. It shows a native search box with a search icon that users can tap. This view exposes the SearchButtonPressed event. You can handle this event to retrieve the text the user typed in the box, and then perform your search logic; for example, by executing a LINQ query against an in-memory collection or filtering data from the table of a local database.

It also exposes the TextChanged event, which is raised at every keystroke, and the Placeholder property, which allows you to specify placeholder text like the same-named property of the Entry control. You declare it as follows:

<SearchBar x:Name="SearchBar1" Placeholder="Enter your search key..."

SearchButtonPressed="SearchBar1_SearchButtonPressed"/>

Figure 36 shows an example.

Figure 36: The SearchBar view

The SearchBar can be a good companion because you can use it to filter a list of items based on the search key the user entered, which is one of the topics discussed in Chapter 7.

Long-running operations: ActivityIndicator and ProgressBar

In some situations, your app might need to perform potentially long-running operations, such as downloading content from the internet or loading data from a local database. In such situations, it is a best practice to inform the user that an operation is in progress.

This can be accomplished with two views: the ActivityIndicator and the ProgressBar. The latter exposes a property called Progress, of type double, and a ProgressColor property, of type Color, that allows you to change the color of the progress indicator. This control is not used very often because it implies you are able to calculate the amount of time or data needed to complete an operation.

The ActivityIndicator shows a simple animated indicator that is displayed while an operation is running, without the need to calculate its progress. It is enabled by setting its IsRunning property to true. You might want to make it visible only when running, which is done by assigning IsVisible with true. You typically declare it in XAML as follows:

<ActivityIndicator x:Name="ActivityIndicator1" />

Then, in the code-behind, you can control it as follows:

// Starting the operation...

ActivityIndicator1.IsVisible = true;

ActivityIndicator1.IsRunning = true;

// Executing the operation...

// Operation completed

ActivityIndicator1.IsRunning = false;

ActivityIndicator1.IsVisible = false;

As a personal suggestion, I recommend you always set both IsVisible and IsRunning. This will help you keep consistent behavior across platforms. Figure 37 shows an example.

Figure 37: The ActivityIndicator shows that an operation is in progress

Tip: Page objects, such as the ContentPage, expose a property called IsBusy that enables an activity indicator when assigned with true. Depending on your scenario, you might also consider this option.

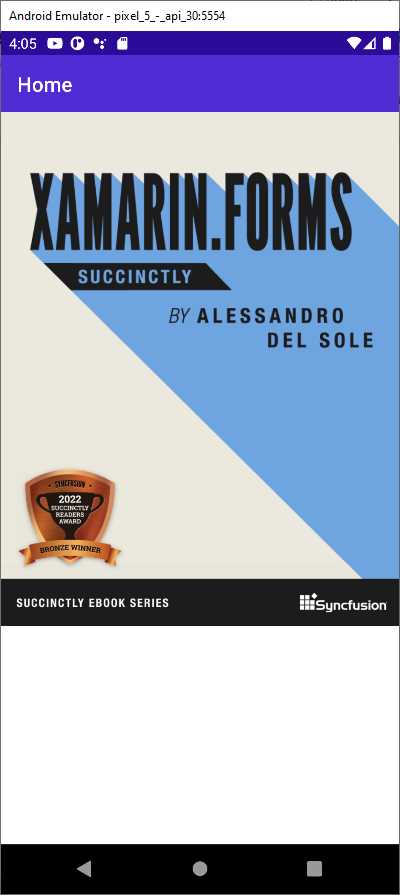

Working with images

Using images is crucial in mobile apps since they both enrich the look and feel of the user interface and enable apps to support multimedia content. .NET MAUI provides the Image control to display images from the internet, local files, and embedded resources.

Displaying images is really simple, but understanding how you load and size images is more complex, especially if you have no previous experience with XAML and dynamic user interfaces. You declare an Image as follows:

<Image Source="https://cdn.syncfusion.com/content/images/downloads/ebook/ebook-cover/2018-bronze-xamarin-forms-succinctly.png" Aspect="AspectFit"/>

As you can see, you assign the Source property with the image path, which can be a URL or the name of a local file or resource. A convenient place to include your local images is the Resources\Images subfolder.

Source can be assigned either in XAML or in code-behind. You will assign this property in C# code when you need to assign the property at runtime. This property is of type ImageSource and, while XAML has a type converter for it, in C# you need to use specific methods depending on the image source. FromFile requires a file path that can be resolved on each platform, FromUri requires a System.Uri object, and FromResource allows you to specify an image in the embedded app resources.

Note: The official documentation provides further explanations about images as embedded resources.

The Aspect property determines how to size and stretch an image within the bounds it is being displayed in. It requires a value from the Aspect enumeration:

· Fill: Stretches the image to fill the display area completely and exactly. This may result in the image being distorted.

· AspectFill: Clips the image so that it fills the display area while preserving the aspect ratio.

· AspectFit: Letterboxes the image (if required) so that the entire image fits into the display area, with blank space added to the top, bottom, or sides, depending on whether the image is wide or tall.

You can also set the WidthRequest and HeightRequest properties to adjust the size of the Image control. Figure 38 shows an example.

Figure 38: Displaying images with the Image view

The supported image formats are .jpg, .png, .gif, .bmp, .tif, and .svg.

Displaying animated GIFs

It is also possible to display animated GIFs. These can be displayed from local storage or streamed online. When an animated .gif file is loaded, you need to explicitly assign the IsAnimationPlaying property with true.

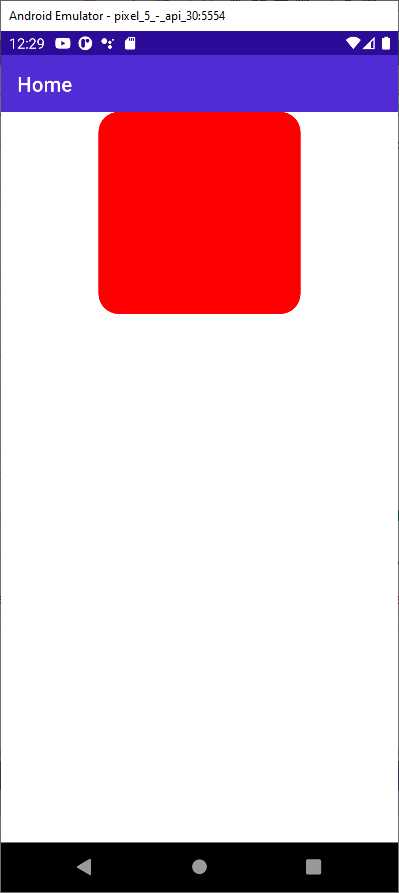

Displaying solid colors with the BoxView

The BoxView is a view that displays a rectangle or square filled with a solid color. It is very easy to use, as demonstrated in the following line:

<BoxView Color="Red" CornerRadius="20" WidthRequest="200" HeightRequest="200"

HorizontalOptions="Center"/>

The size and position changes depending on the parent container. You can optionally assign the CornerRadius property if you want to add round corners. Figure 39 shows an example.

Figure 39: Displaying a BoxView

Introducing gesture recognizers

Views such as Image and Label do not include support for touch gestures natively, but sometimes you might want to allow users to tap a picture or text to perform an action, such as navigating to a page or website. The Microsoft.Maui.Controls namespace has classes that allow you to leverage gesture recognizers to add touch support to views that do not include it out of the box.

Note: The documentation for gesture recognizers can be found here.

Views expose a collection called GestureRecognizers, of type IList<GestureRecognizer>. Supported gesture recognizers are:

· TapGestureRecognizer: Allows recognition of taps.

· PinchGestureRecognizers: Allows recognition of the pinch-to-zoom gesture.

· PanGestureRecognizers: Enables dragging of objects with the pan gesture.

For example, the following XAML demonstrates how to add a TapGestureRecognizer to an Image control:

<Image Source="https://www.xamarin.com/content/images/pages/branding/assets/xamarin-logo.png" Aspect="AspectFit">

<Image.GestureRecognizers>

<TapGestureRecognizer x:Name="ImageTap"

NumberOfTapsRequired="1" Tapped="ImageTap_Tapped"/>

</Image.GestureRecognizers>

</Image>

You can assign the NumberOfTapsRequired property (self-explanatory) and the Tapped event with a handler that will be invoked when the user taps the image. It will look like this:

private void ImageTap_Tapped(object sender, EventArgs e)

{

// Do your stuff here...

}

Gesture recognizers give you great flexibility and allow you to improve the user experience in your mobile apps by adding touch support where required.

Displaying alerts

All platforms can show pop-up alerts with informative messages or receive user input with common choices such as OK or Cancel. Pages in .NET MAUI provide an asynchronous method called DisplayAlert, which is very easy to use.

For example, suppose you want to display a message when the user taps a button. The following code demonstrates how to accomplish this:

private async void Button1_Clicked(object sender, EventArgs e)

{

await DisplayAlert("Title", "This is an informational pop-up", "OK");

}

As an asynchronous method, you call DisplayAlert with the await operator, marking the containing method as async. The first argument is the pop-up title, the second argument is the text message, and the third argument is the text you want to display in the only button that appears. Actually, DisplayAlert has an overload that can wait for the user input and return true or false depending on whether the user selected the OK option or the Cancel option:

bool result =

await DisplayAlert("Title", "Do you wish to continue?", "OK", "Cancel");

You are free to write whatever text you like for the OK and Cancel options, and IntelliSense helps you understand the order of these options in the parameter list. If the user selects OK, DisplayAlert returns true. Figure 40 shows an example of the alert.

Figure 40: Displaying alerts

Displaying action sheets

An action sheet is a more sophisticated list of options that you can show inside a system alert and let the user make their choice. An action sheet is displayed via the DisplayActionSheet asynchronous method, like in the following example:

string result =

await DisplayActionSheet("Select the destination", "Cancel",

"Delete file", "Microsoft OneDrive", "Google Drive",

"Apple iCloud", "Local device");

The preceding code simulates a list of potential targets for a file that is being created or copied. The first argument for the method is the alert title. The second argument is the string for the Cancel button. The third argument is known as the destruction option and allows for providing a command that represents a destructive action (in this case the file deletion).

This is an optional argument and can be assigned with null if you do not need a destruction option. Then you can specify as many options as you like, all of type string. The result of the method call is a string containing the text of the option that the user selected from the action sheet. Figure 41 shows how the sample action sheet looks.

Figure 41: Displaying action sheets

Displaying action prompts

Sometimes you might need a quick and easy way to accept user input without implementing sophisticated visual elements. In this case, you can use a so-called action prompt. In its simplest form, you declare an action prompt as follows:

string promptResult =

await DisplayPromptAsync("Welcome question",

"Where did you hear about us from?");

The result is represented in Figure 42.

Figure 42: Displaying action prompts

The result of the method is a string. You can further customize the action prompt by specifying the text for the OK button (third argument), the Cancel button (fourth argument), the placeholder (fifth argument), the maximum length for the input text (sixth argument), the keyboard type (seventh argument), and an initial value (eighth argument).

The keyboard type is of type Keyboard, and you can specify the same values used with the Entry view.

Introducing the Visual State Manager

With the Visual State Manager, you can make changes to the user interface based on a view’s state, such as Normal, Focused, or Disabled, all with declarative code. For example, you can use the Visual State Manager to change the color of a view depending on its state.

The following code snippet demonstrates how you can change the background color of an Entry view based on its state:

<Entry>

<VisualStateManager.VisualStateGroups>

<VisualStateGroup x:Name="CommonStates">

<VisualState x:Name="Normal">

<VisualState.Setters>

<Setter Property="BackgroundColor" Value="White" />

</VisualState.Setters>

</VisualState>

<VisualState x:Name="Focused">

<VisualState.Setters>

<Setter Property="BackgroundColor"

Value="LightGray" />

</VisualState.Setters>

</VisualState>

<VisualState x:Name="Disabled">

<VisualState.Setters>

<Setter Property="BackgroundColor" Value="Gray" />

</VisualState.Setters>

</VisualState>

</VisualStateGroup>

</VisualStateManager.VisualStateGroups>

</Entry>

With this markup, the Entry will automatically change its background color when its state changes. In this case, you will need to set the Entry’s IsEnabled property as False in order to disable the view and trigger the Disabled state.

States must be grouped into objects called VisualStateGroup. Each state is represented by the VisualState object, where you add Setter specifications as you would do with styles, therefore providing the name of the property you want to change and its value.

Of course, you can specify multiple property setters. .NET MAUI, as well as all the other platforms based on XAML, defines a set of states called common states, such as Normal, Focused, and Disabled (see the VisualStateGroup with the CommonState name in the preceding code); these states are common to each view.

Other states might be available only to specific views and not to other views. The Visual State Manager provides an elegant and clean way to control the user interface behavior, all in your XAML code.

Chapter summary

This chapter introduced the concepts of view and common views in .NET MAUI, the building blocks for any user interface in your mobile apps. You have seen how to obtain user input with the Button, Entry, Editor, and SearchBar controls, how to display information with the Label, and how to use it in conjunction with other input views, such as Slider, Stepper, CheckBox, RadioButton, and Switch.

You have seen the DatePicker and TimePicker views and how they allow you to work with dates and time. You have learned how to display images with the Image view and videos with the MediaElement. You have seen how the WebView is used to show HTML content and how to inform users of the progress of long-running operations with ActivityIndicator and ProgressBar.

You have also learned how to add gesture support to views that do not include it out of the box, how to display alerts for informational purposes, and how to provide choices to users. Finally, you have seen how the Visual State Manager allows changing the user interface behavior based on a view’s state with declarative code.

Now you have all you need to build high-quality user interfaces with layouts and views, but you have only seen how to use these building blocks in a single page. Most mobile apps are made of multiple pages. The next chapter explains all the available page types in MAUI and the navigation infrastructure.

- An ever-growing .NET MAUI control suite with rich feature sets.

- DataGrid, Charts, ListView, Scheduler, and more.

- Active community and dedicated support.

- Phone, tablet, and desktop support.