CHAPTER 3

Heap and Priority Queue

Overview

The heap data structure is one that provides two simple behaviors:

- Allow values to be added to the collection.

- Return the minimum or maximum value in the collection, depending on whether it is a “min” or “max” heap.

While these behaviors might seem simplistic at first, this simplistic nature allows the data structure to be implemented very efficiently, both in terms of time and space, while providing a behavior that is commonly needed.

One easy way to think about a heap is as a binary tree that has two simple rules:

- The child values of any node are less than the node’s value.

- The tree will be a complete tree.

Don’t read anything more into rule #1 than it says. The children of any node will be less than, or equal to, their parent. There is nothing about ordering, unlike a binary search tree where ordering is very important.

So what does rule #2 mean? A complete tree is one where every level is as full as possible. The only level that might not be full is the last (deepest) level, and it will be filled from the left to the right.

When these rules are applied recursively through the tree, it should be clear that every node in a heap is itself the parent node of a sub-heap within the heap.

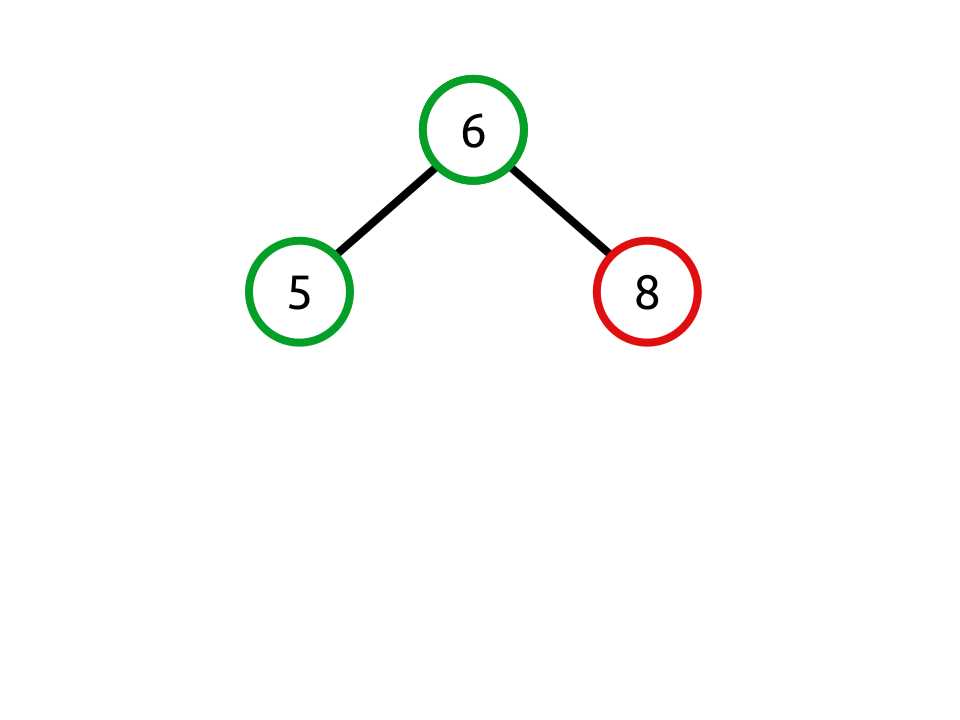

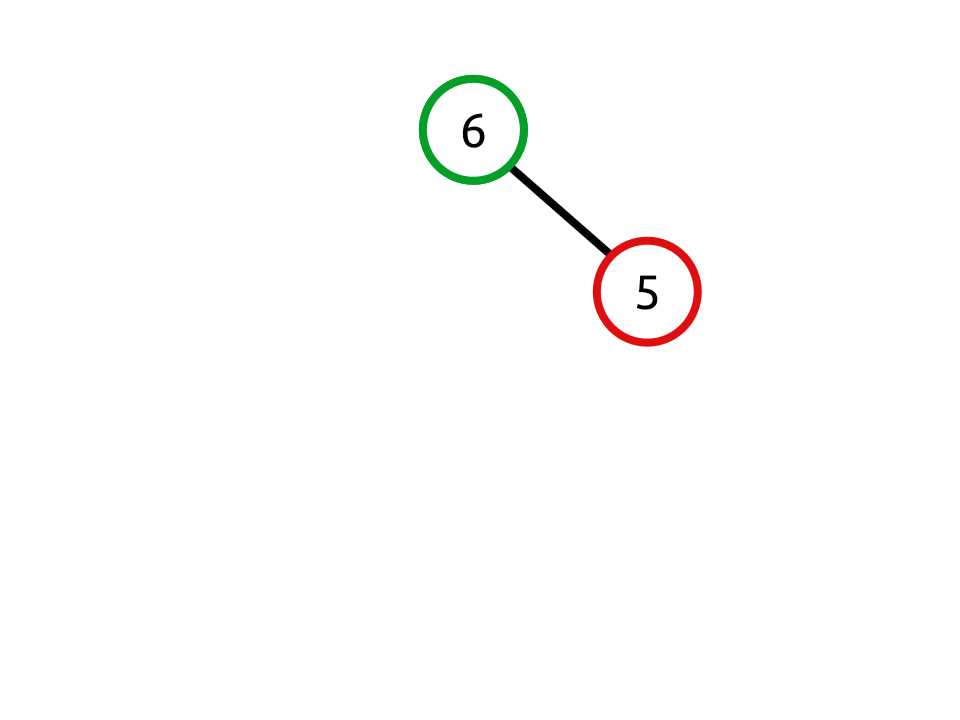

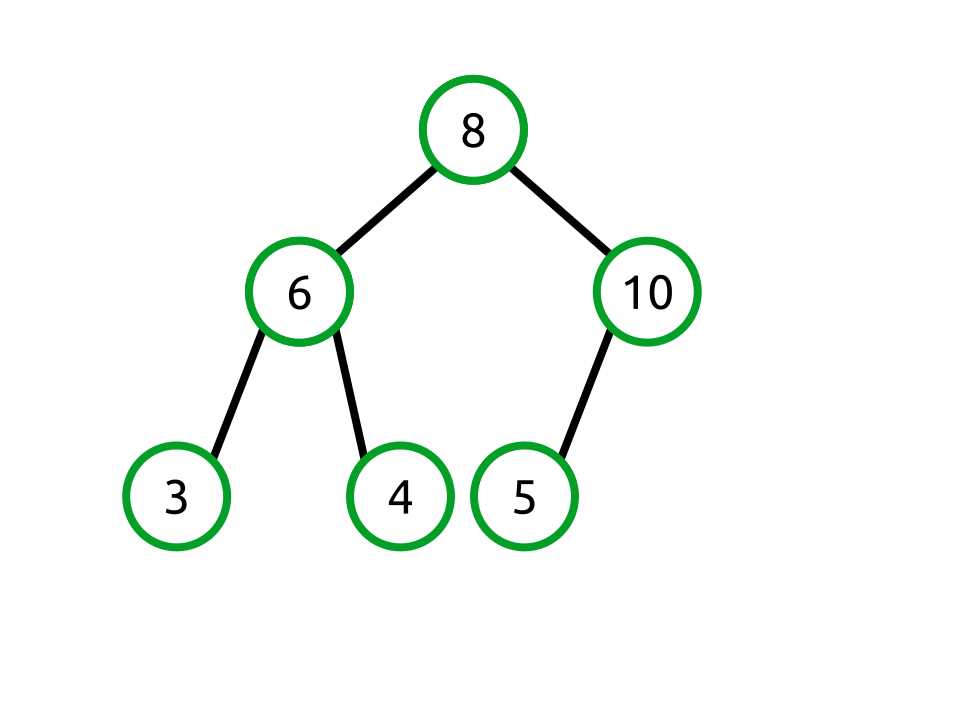

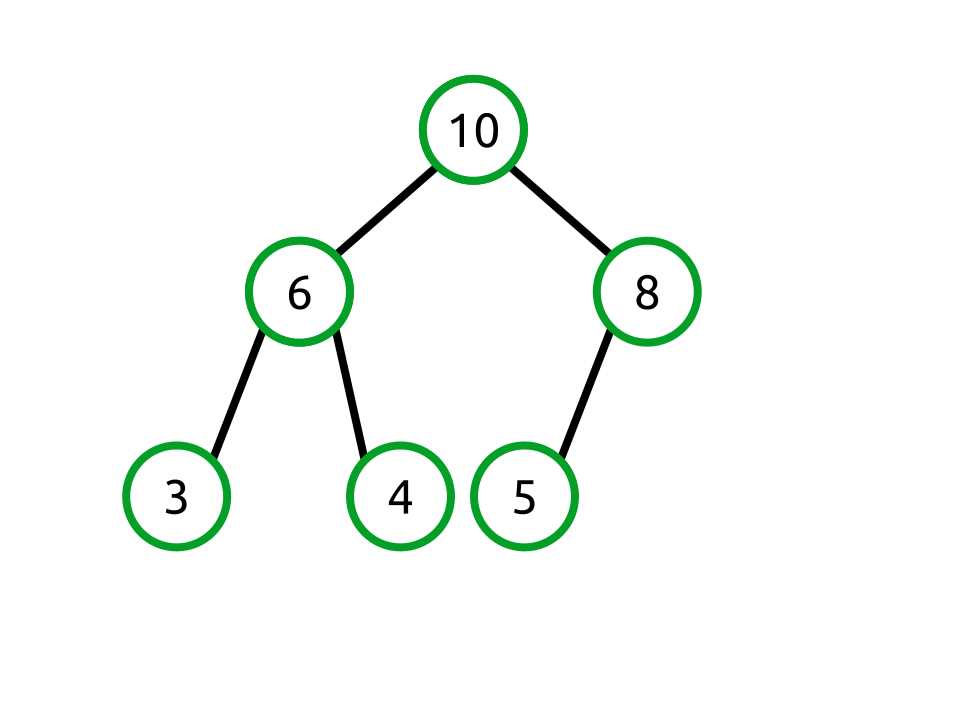

Let’s look at some invalid heap trees:

Figure 16: Invalid because the child value 8 is greater than the parent value 6

Figure 17: Invalid because the child node is filled in on the right, not the left

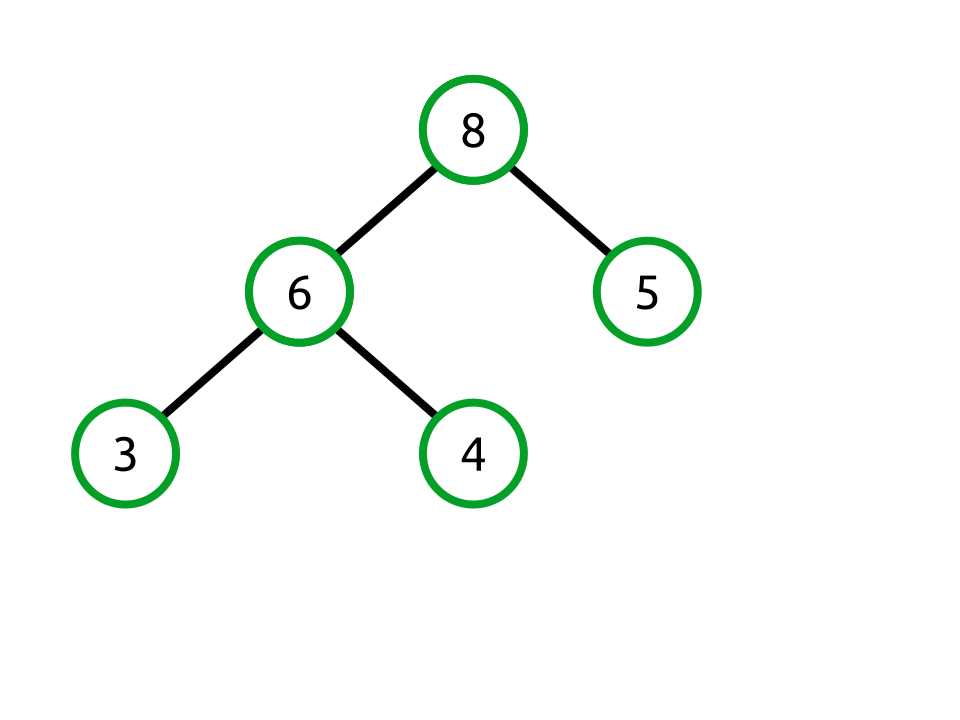

And now a valid heap:

Figure 18: Valid heap in which the property and completeness rules are both followed

Binary Tree as Array

Structural Overview

While heaps conceptually map to trees very easily, in practice they are typically not stored in a tree structure. Rather, the tree structure is projected into an array using a very simple algorithm. Because we are using a complete tree, this becomes a very simple operation.

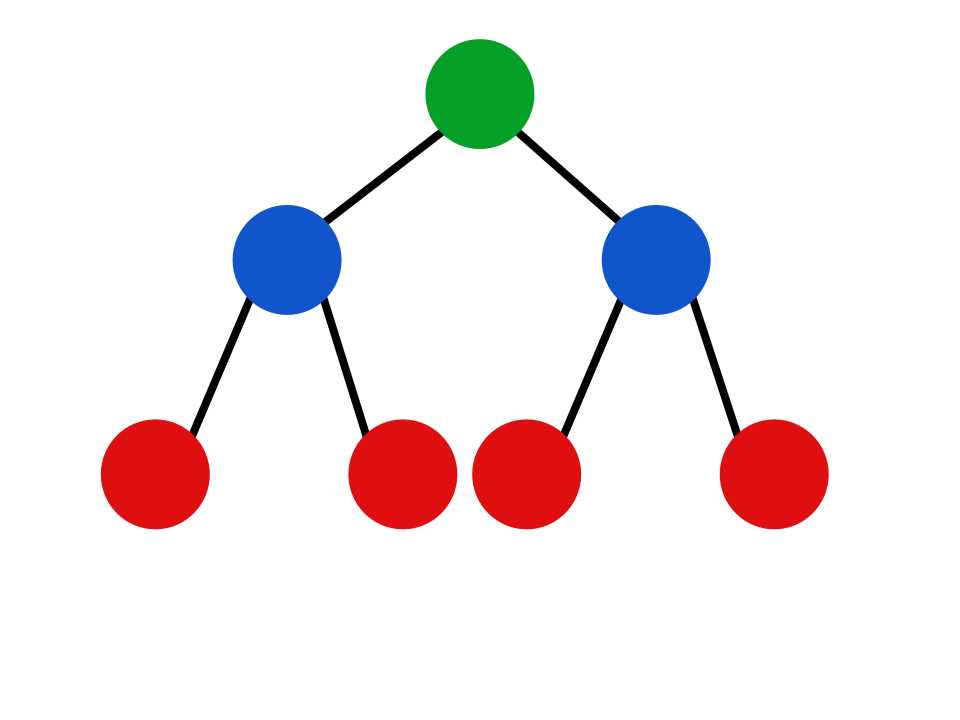

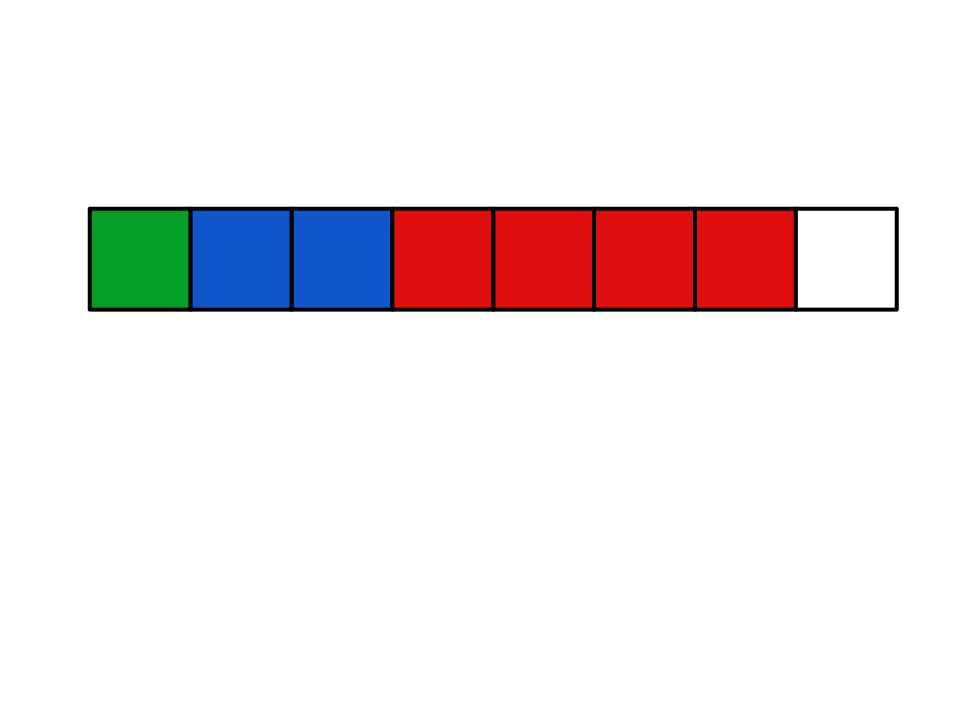

Let’s start by looking at a tree whose nodes are colored based on what level they are in within the tree.

Figure 19: Tree with colors based on level

This is a complete tree with seven nodes across three levels. We fit this level-by-level into an array like so:

Figure 20: The binary tree projected into the array

The root node (level 1) is in the first array index. Its children (the next level) follow. Their children follow. This pattern continues for every level of the tree. Notice there is even an unused array index at the end of the array. This will become important when we want to add more data to the heap.

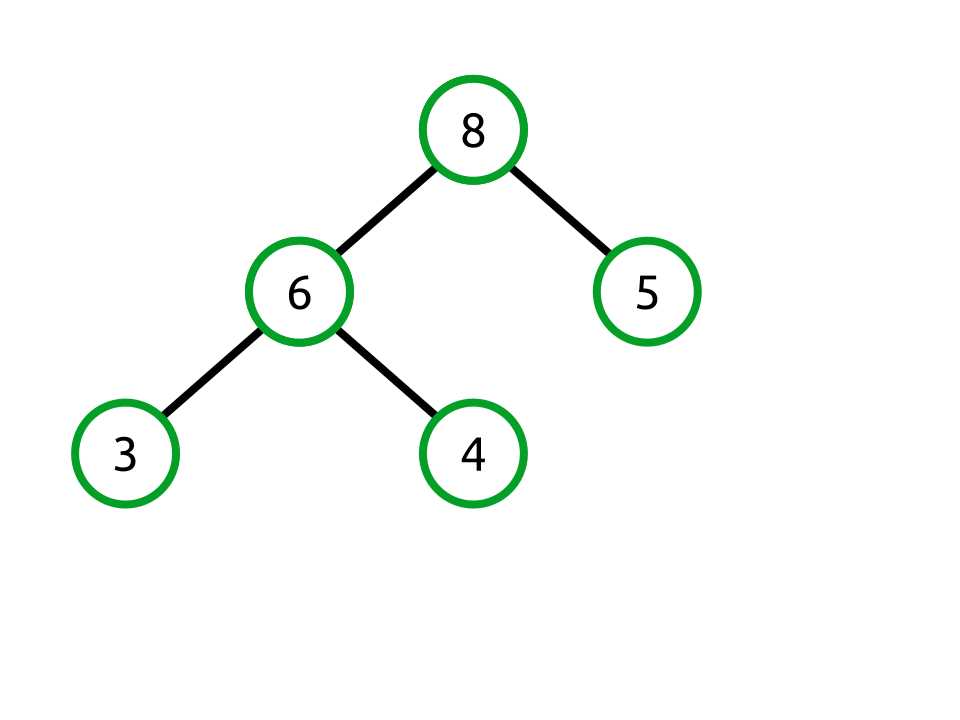

Let’s look at a concrete example where this valid heap maps into an array.

Figure 21: A valid heap as a binary tree

Figure 22: The valid heap tree mapped into an array

Navigating the Array like a Tree

One of the nice benefits of trees is that they are very easy to navigate both in an iterative and recursive fashion. Moving up or down the tree is as simple as navigating to the child nodes or back up to the parent.

If we are going to efficiently use an array to contain our tree data, we need to have equally efficient mechanisms to determine two facts:

- Given an index, what indexes represent its children?

- Given an index, what index represents its parent?

It turns out this is very simple.

The children of any index are:

- Left child index = 2 × <current index> + 1

- Right child index = 2 × <current index> + 2

Let’s prove that works. Recall that the root node is stored in index 0. Using the formula, we see that its left child can be found at index 1 (using the formula 2 × 0 + 1) and its right child at index 2 (2 × 0 + 2).

Finding the parent of any node is simply the inverse of that function:

Parent = (index - 1) / 2

Technically, it is floor((index - 1) / 2). However, C# handles the integer truncation for us.

The Key Point

The critical point to take away from this section is this: the largest value in the heap is always the first item in the array.

Heap Class

The heap class we will be implementing is a max heap, meaning that it returns the maximum value very efficiently. The class is very straightforward. It has a method to add a new value, remove the maximum value, peek at the maximum value, clear the collection, and get the current count of items in the heap.

The heap requires that its generic type argument implements the IComparable<T> interface and has two fields: the backing array and the current count of items in the heap. Two utility methods, Swap and Parent, are shown here as well.

Notice that there are no methods for enumeration or performing other look-up operations such as determining if the heap contains a specific value or directly indexing into the heap. While those methods would not be terribly difficult to add, they are in conflict with what a heap is. A heap is an opaque container that returns the minimum or maximum value.

public class Heap<T> where T: IComparable<T> { T[] _items; int _count; const int DEFAULT_LENGTH = 100; public Heap() : this(DEFAULT_LENGTH) { } public Heap(int length) { _items = new T[length]; _count = 0; } public void Add(T value); public T Peek(); public T RemoveMax(); public int Count { get; } public void Clear(); private int Parent(int index) { return (index - 1) / 2; } private void Swap(int left, int right) { T temp = _items[left]; _items[left] = _items[right]; _items[right] = temp; } } |

Add

Behavior | Adds the provided value to the heap. |

Performance | O(log n) |

Adding a value to the heap has two steps:

- Add the value to the end of the backing array (growing if necessary).

- Swap the value with its parent until the heap property is satisfied.

For example, let’s look at our valid heap from before:

Figure 23: Valid heap

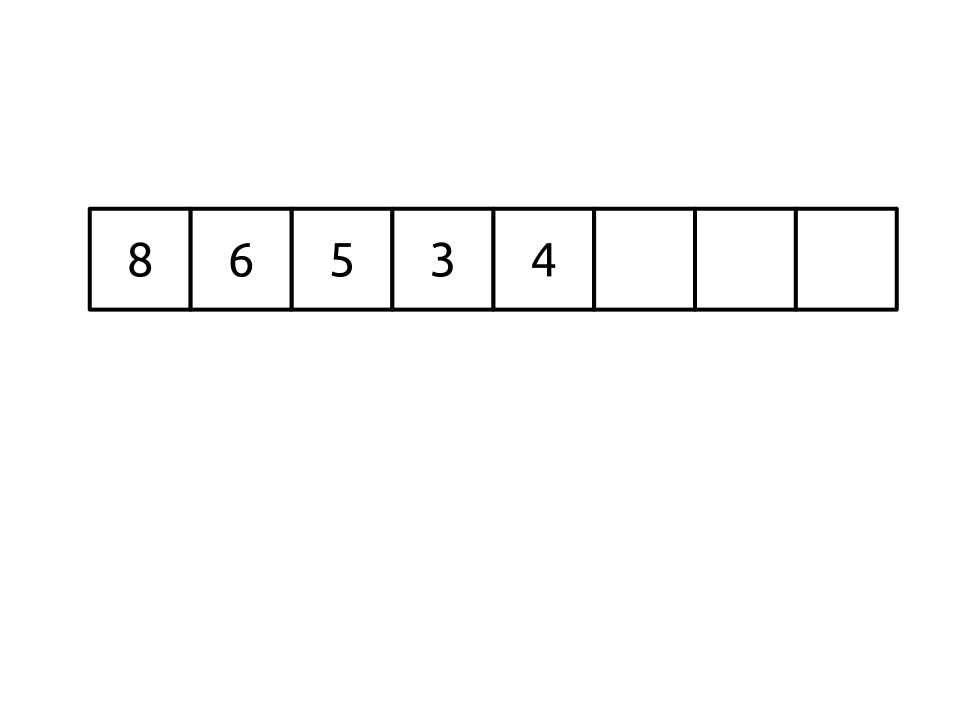

We are going to add the value 10 to the heap. Using the algorithm described, we start by adding the value to end of the backing array. Since we are storing a complete tree in the array, this means we are adding a new node to the leftmost free slot on the last level.

Figure 24: Adding 10 to the valid heap

Our backing array now looks like the following:

[8, 6, 5, 3, 4, 10] |

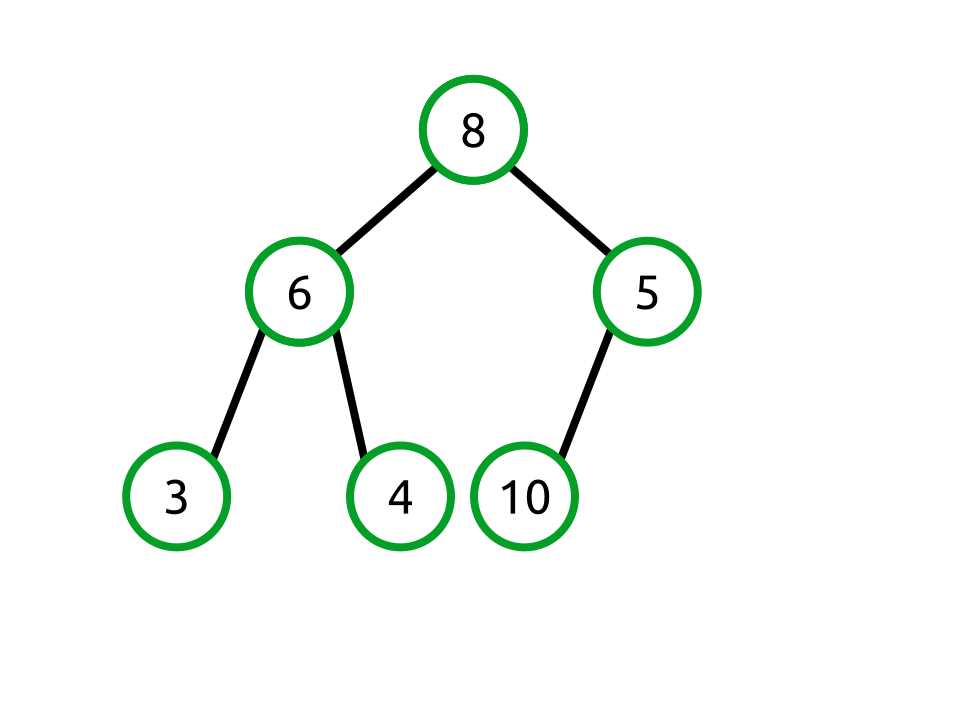

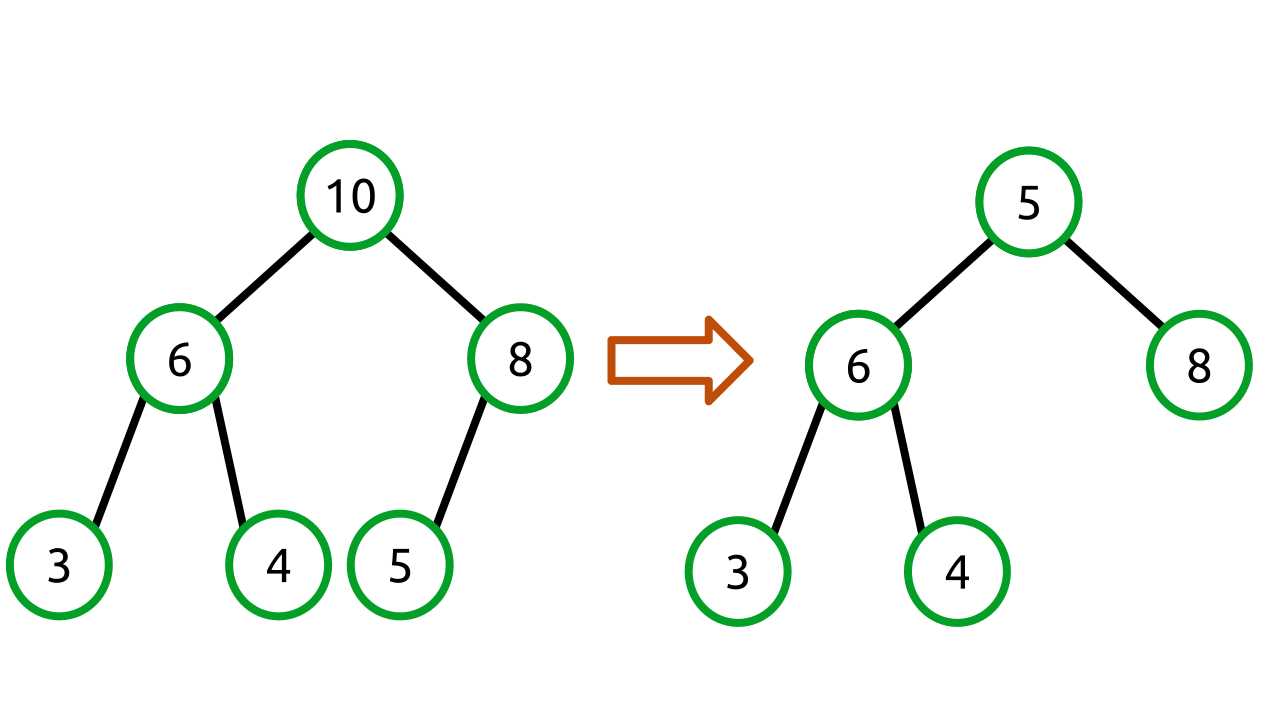

You should notice that this violates the heap property that requires each node’s children to be less than or equal to the parent node’s value. In this case, the value 5 has a child whose value is 10. To fix this, we need to swap the nodes like so:

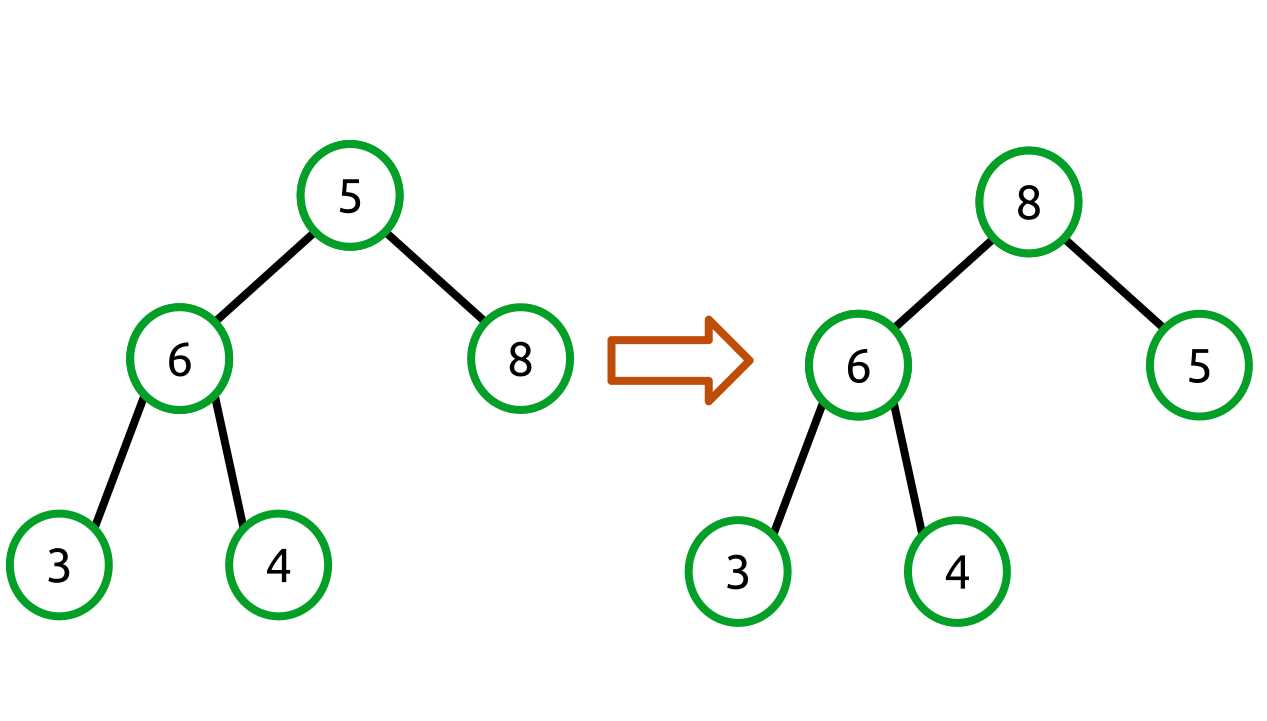

Figure 25: Swapping the 10 and 5 nodes

Our backing array now looks like this:

[8, 6, 10, 3, 4, 5] |

We have now fixed the relationship between 10 and 5, but the parent node of 10 is 8, and that violates the heap property, so we need to swap those as well.

Figure 26: Swapping the 10 and 8 nodes

Our backing array now looks like the following:

[10, 6, 8, 3, 4, 5] |

The tree now satisfies the heap property and is still complete, thus the Add operation is complete.

Notice that as the tree rebalanced, the operation performed in the array was a simple swap of the values at the parent and child indexes.

public void Add(T value) { if (_count >= _items.Length) { GrowBackingArray(); } _items[_count] = value; int index = _count; while (index > 0 && _items[index].CompareTo(_items[Parent(index)]) > 0) { Swap(index, Parent(index)); index = Parent(index); } _count++; } private void GrowBackingArray() { T[] newItems = new T[_items.Length * 2]; for (int i = 0; i < _items.Length; i++) { newItems[i] = _items[i]; } _items = newItems; } |

RemoveMax

Behavior | Removes and returns the largest value in the heap. An exception is thrown if the heap is empty. |

Performance | O(log n) |

RemoveMax works similar to Add, but in the opposite direction. Where Add starts at the bottom of the tree (or the end of the array) and works the value upward to its appropriate location, RemoveMax starts by storing away the largest value in the heap which is in array index 0. This is the value that will be returned to the caller.

Since that value is being removed, the array index 0 is now free. To ensure that our array does not have any gaps, we need to move something into it. What we do is grab the last item in the array and move it forward to index 0. In a tree view it would look like this:

Figure 27: Moving the last array item to index 0

Our backing array changes like so:

[10, 6, 8, 3, 4, 5] => [5, 6, 8, 3, 4] |

As with Add, the tree is not in a valid state. However, unlike Add, the bad node is the root (array index 0) rather than the last node.

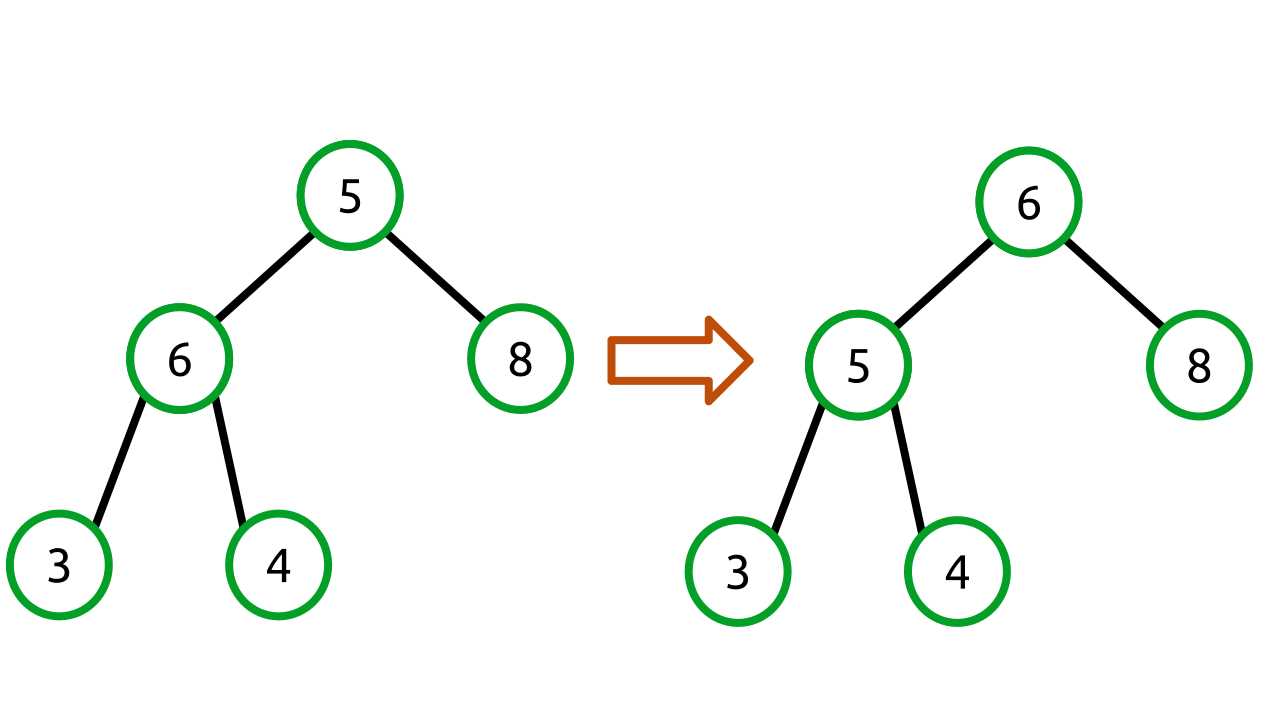

What we need to do is swap the smaller parent node with its children until the heap property is satisfied. This just leaves the question: what child do we swap with? The answer is that we always swap with the largest child. Consider what would happen if we swapped with the lesser child. The tree would switch from one invalid state to another. For example:

Figure 28: Swapping with the lesser value does not create a valid heap

We haven’t solved the problem! Instead, we need to swap with the larger of the two children like so:

Figure 29: Swapping with the largest child creates a valid heap

Our backing array changes like so:

[5, 6, 8, 3, 4] => [8, 6, 5, 3, 4] |

This example required only a single swap for the heap to be valid. In practice though, the swap operation may need to be performed at each level until the heap property is satisfied or until the node is at the last level (possibly back where it started).

public T RemoveMax() { if (Count <= 0) { throw new InvalidOperationException(); } T max = _items[0]; _items[0] = _items[_count - 1]; _count--; int index = 0; while (index < _count) { // Get the left and right child indexes. int left = (2 * index) + 1; int right = (2 * index) + 2; // Make sure we are still within the heap. if (left >= _count) { break; } // To avoid having to swap twice, we swap with the largest value. // E.g., // 5 // 6 8 // // If we swapped with 6 first we'd have // // 6 // 5 8 // // and we'd require another swap to get the desired tree. // // 8 // 6 5 // // So we find the largest child and just do the right thing at the start. int maxChildIndex = IndexOfMaxChild(left, right); if (_items[index].CompareTo(_items[maxChildIndex]) > 0) { // The current item is larger than its children (heap property is satisfied). break; } Swap(index, maxChildIndex); index = maxChildIndex; } return max; } private int IndexOfMaxChild(int left, int right) { // Find the index of the child with the largest value. int maxChildIndex = -1; if (right >= _count) { // No right child. maxChildIndex = left; } else { if (_items[left].CompareTo(_items[right]) > 0) { maxChildIndex = left; } else { maxChildIndex = right; } } return maxChildIndex; } |

Peek

Behavior | Returns the maximum value in the heap or throws an exception if the heap is empty. |

Performance | O(1) |

public T Peek() { if (Count > 0) { return _items[0]; } throw new InvalidOperationException(); } |

Count

Behavior | Returns the number of items in the heap. |

Performance | O(1) |

public int Count { get { return _count; } } |

Clear

Behavior | Removes all the items from the heap. |

Performance | O(1) |

Clear sets the count to 0 and allocates a new default-length array. The array allocation is done to ensure that the garbage collector has a chance to free any objects that were referenced by the heap before Clear was called.

public void Clear() { _count = 0; _items = new T[DEFAULT_LENGTH]; } |

Priority Queue

A priority queue is a cross between a queue and heap. It looks and feels like a queue—items can be enqueued and dequeued. However, the value that is returned is the highest priority item.

Priority queues are commonly used in scenarios where many items are being processed, some of which are more important than others.

Network routing is an example I think we can all relate to. Not all network traffic is equal. Some data, such as real-time voice communications, requires a high quality of service while other data, such as background file transfers for a network backup program, require a lower quality of service.

If my computer is sending packets for both a VoIP phone connection and transferring pictures of my vacation to Facebook, it is very likely that I want the voice connection to take priority over the picture transfer. I probably won’t notice if the picture transfer takes a little longer, but you can be sure I will notice if my voice call quality is poor.

In this example, the network stack might provide a mechanism that allows the network traffic to declare some priority property for itself which determines how time-sensitive the data is. The network stack might use a priority queue internally to make this happen. This is obviously a trivialization of a complex topic, but the point should be clear: some data sets are more important than others.

Priority Queue Class

The priority queue class is a very thin wrapper over a heap. All it really does is wrap the Add and RemoveMax methods with Enqueue and Dequeue, respectively.

public class PriorityQueue<T> where T: IComparable<T> { Heap<T> _heap = new Heap<T>(); public void Enqueue(T value) { _heap.Add(value); } public T Dequeue() { return _heap.RemoveMax(); } public void Clear() { _heap.Clear(); } public int Count { get { return _heap.Count; } } } |

Usage Example

This example creates a simple application where messages are queued with these:

- A priority from 0 (lowest) to 3 (highest).

- The age of the message.

- The message itself (a string).

A priority queue is used to ensure that messages are processed in order of priority. Multiple messages within a given priority are processed from oldest to newest.

The Data class has the three properties noted in the previous list, a ToString method to print the properties in a structured manner, and an IComparable<Data>.CompareTo method that performs a comparison by Priority and Age.

class Data : IComparable<Data> { readonly DateTime _creationTime; public Data(string message, int priority) { _creationTime = DateTime.UtcNow; Message = message; Priority = priority; } public string Message { get; private set; } public int Priority { get; private set; } public TimeSpan Age { get { return DateTime.UtcNow.Subtract(_creationTime); } } public int CompareTo(Data other) { int pri = Priority.CompareTo(other.Priority); if (pri == 0) { pri = Age.CompareTo(other.Age); } return pri; } public override string ToString() { return string.Format("[{0} : {1}] {2}", Priority, Age.Milliseconds, Message); } } |

Next, there is a simple class that adds 1000 random-priority messages to the queue with a short, 0–3 millisecond delay between messages to ensure that ordering can be demonstrated both by priority and time.

The application then prints out the messages in priority and age order to demonstrate how the priority queue can be used.

static void PriorityQueueSample() { PriorityQueue<Data> queue = new PriorityQueue<Data>(); queue = new PriorityQueue<Data>(); Random rng = new Random(); for (int i = 0; i < 1000; i++) { int priority = rng.Next() % 3; queue.Enqueue(new Data(string.Format("This is message: {0}", i), priority)); Thread.Sleep(priority); } while (queue.Count > 0) { Console.WriteLine(queue.Dequeue().ToString()); } } |

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.