CHAPTER 6

Shared Memory

Shared memory is a small amount of on-chip memory, ranging from 16 kilobytes to 48 kilobytes, depending on the configuration of the kernel. Remember that the term “on-chip” means inside the main processor of the graphics card (the chip is marked B in Figure 3.6).

Shared memory is very fast, approaching register speeds, but only when used optimally. Shared memory is allocated and used per block. All threads within the same thread block share the same allocation of shared memory, and each block allocation of shared memory is not visible to the other blocks running in the grid.

Because of the speed difference between global memory and shared memory, using shared memory is almost always preferred if the operation you’re going to perform permits efficient use of it. In this chapter, we will examine the efficient use of shared memory, but first we need to learn the syntax and API calls for basic shared memory usage.

Static and Dynamic Allocation

Shared memory can be allocated per block in one of two ways: static or dynamic. The static method is less flexible and requires that the amount of shared memory be known at compile time. The dynamic method is slightly more complicated (syntactically), but allows for the amount of shared memory to be specified at runtime.

Statically Allocated Shared Memory

To declare that a variable in a kernel is to be stored in shared memory, use the __shared__ qualifier keyword beside the variable's name in its definition (see Listing 6.1).

__global__ void MyKernel() { __shared__ int i; // Shared int __shared__ float f_array[10]; // 10 shared floats // ... Some other code } |

Listing 6.1: Statically Allocated Shared Memory

Listing 6.1 shows two variables declared as __shared__, an integer called i, and a floating point array called f_array. This shared memory (both the i and the f_array variables) are described as being statically allocated because the amount of shared memory must be constant at compile-time. Here, we are allocating an int and ten floats per block, for a total of 44 bytes of shared memory per block (both int and float are 4 bytes long).

All the threads in a given block will share these variables. Every block launched in a grid will allocate its own copy of these variables. If we launch a grid of 25 blocks, there will be 25 copies of i and 25 copies of f_array in shared memory. If the device does not have enough shared memory to allocate all 25 copies of the requested shared memory, then it cannot execute all the blocks simultaneously. The device executes as many blocks as it can simultaneously, but when there are not enough resources, it schedules some blocks to execute after others. Shared memory is one of the most important resources of the device and careful allocation of shared memory is an important factor for determining occupancy, which is described in Chapter 8.

Dynamically Allocated Shared Memory

The other way to allocate shared memory is to dynamically allocate it. This allows the amount of shared memory per kernel to change from launch to launch. In other words, the amount need not be a compile-time constant. To allocate a dynamic amount of shared memory for a kernel, we need to supply a third argument in the kernel launch configuration from the host. The code in Listing 6.2 shows an example launch configuration with this third parameter.

// Kernel __global__ void SomeKernel() { // The size of the following is set by the host extern __shared__ char sharedbuffer[]; } int main() { // Other code // Host launch configuration SomeKernel<<<10, 23, 32>>>(); // Other code } |

Listing 6.2: Dynamic Shared Memory Allocation

The kernel launch configuration parameters (in the main method) specify to launch the kernel with 10 blocks of 13 threads each. The final parameter is the amount of dynamic shared memory to allocate per block. The parameter is measured in bytes, so the value 32 here would mean that 32 bytes of shared memory should be allocated per block. The 32 bytes can be used for many different purposes—they could be 8 floats, 16 shorts, 32 chars, or any combination of data types that would consume 32 bytes.

The kernel declares the shared array as extern __shared__, which means that the amount of shared memory is dynamic and will be determined by the host in the launch configuration. In the previous example, the shared array is of char type, but it could be any type at all. Also, the 32 bytes of shared memory per block were specified in the launch configuration with a literal constant, but this amount can be a variable.

Using Dynamic Shared Memory as Multiple Data

The launch configuration only allows a single extra value to specify the amount of dynamic shared memory per block. If an algorithm requires multiple arrays of shared memory per block, the programmer must allocate a single store of shared memory and use pointers to access it. In other words, if you need multiple dynamic shared memory arrays, they must be coordinated manually. Listing 6.3 shows an example of using a single block of shared memory for two arrays, one of chars and the other of floats.

__global__ void SomeKernel(int sizeofCharArray) { // Declare a single dynamic store of shared memory per block extern __shared__ char bothBuffers[]; // Make a char* pointer to the first element char* firstArray = &bothBuffers[0]; // Make a float* pointer to some other element float* secondArray = (float*)&bothBuffers[sizeofCharArray]; firstArray[0]++; // Increment first char secondArray[0]++; // Increment first float } |

Listing 6.3: Using Two Dynamic Arrays

In this listing, the same dynamic shared memory allocation (called bothBuffers) is used for both a character array (firstArray) and a floating point array (called secondArray). Obviously, care must be taken not to read and write outside of the bounds of these arrays.

In the listing, the size of the character array is specified and passed as a parameter to the kernel, sizeOfCharArray. Passing offsets and array sizes as parameters to the kernel allows arrays of variable types and sizes. The bothBuffers array used dynamic shared memory, but it could easily be a static allocation, and the sizeOfCharArray parameter could still be used to manually control the sizes of the arrays.

CUDA Cache Config

As mentioned previously, the L1 cache of global memory and shared memory are actually the same physical memory. There is 64k (on all current cards) of this memory, and it can be split up by the programmer to use more L1, more shared memory, or the same amount of both. The L1 is a perfectly normal, automatic cache for global memory. Data is stored in the L1 cache and evicted as the device sees necessary. Shared memory is completely in the programmer's control.

When launching a kernel you can split this 64k of memory into 48k of L1 and 16k of shared memory. You might also use 16k of L1 and 48k of shared memory. On newer cards (700 series onwards) there is another option, which is to split the memory in half—32k of L1 and 32k of shared. To set the configuration of shared memory and L1 for a particular kernel, use the cudaFuncSetCacheConfig function:

cudaFuncSetCacheConfig(kernelName, enum cudaFuncCache);

Where kernelName is the kernel and cudaFuncCache is one of the values from the cudaFuncCache column of Table 6.1.

Table 6.1: cudaFuncCache values

cudaFuncCache | Integer value | Configuration |

|---|---|---|

cudaFuncCachePreferNone | 0 | Default |

cudaFuncCachePreferShared | 1 | 48k of shared, 16k of L1 |

cudaFuncCachePreferL1 | 2 | 16k of shared, 48k of L1 |

cudaFuncCachePreferEqual | 3 | 32k of shared, 32k of L1 |

Note: The cudaFuncCachePreferEqual setting is only available on newer cards—700 series and newer. If this setting is selected for an older card, the default value will be used instead.

Whatever value the programmer uses for the cudaFuncCache setting, it is only a recommendation to NVCC. If NVCC decides that, despite this setting, the kernel needs more shared memory, then it will override the settings and choose the 48k of shared memory setting. This overriding of the programmer’s preference occurs at compile time, not while the program runs.

The following code example demonstrates how to call the cudaFuncSetCacheConfig function.

// Set the cache config for SomeKernel to 48k of L1 cudaFuncSetCacheConfig(SomeKernel, cudaFuncCachePreferL1); // Call the kernel SomeKernel<<<100, 100>>>(); |

Listing 6.4: Setting the Cache Configuration

Parallel Pitfalls and Race Conditions

This section highlights some dangers of sharing resources between concurrent threads. When resources are shared between multiple threads (this includes any shared resources from global memory, shared memory, texture memory etc.) a potential hazard arises that is not present in serial code. Unless care is taken to properly coordinate access to shared resources, multiple threads may race for a resource at precisely the same time. This results in code that is often unpredictable and buggy. The outcome of multiple threads simultaneously altering the value of a resource is unknown (for practical purposes it is not safe to assume any particular value).

To understand how a race condition causes trouble and why it results in unpredictable outcomes, consider how a computer actually operates on variables in memory. Listing 6.5 illustrates a simple kernel with code that purposely causes two race conditions, one in shared memory, and the other in global memory.

|

#include <cuda.h> using namespace std; // Kernel with race conditions __global__ void Racey(int* result) { __shared__ int i; // Race condition 1, shared memory i = threadIdx.x; // Race condition 2, global memory result[0] = i; } int main() { int answer = 0; int* d_answer; cudaMalloc(&d_answer, sizeof(int)); Racey<<<1024, 1024>>>(d_answer); cudaMemcpy(&answer, d_answer, sizeof(int), cudaMemcpyDeviceToHost); cout<<"The result was "<<answer<<endl; return 0; } |

Listing 6.5: Race Conditions

The kernel declares a single shared integer called i. Each thread attempts to set this shared variable to its own threadIdx.x. Each thread in a block has a different threadIdx.x. In theory, all 1024 threads of each block would simultaneously set this shared variable to different values. This is only “in theory” because the scheduler is in charge of the order that blocks actually execute, and depending on the availability of resources, the scheduler may or may not execute all 1024 threads at the same time. Regardless of whether the scheduler actually executes the threads simultaneously, or if some threads execute after others, setting the variable i to 1024 different values is meaningless. This type of activity is not conducive to productive software development. In practice, the actual resulting i will be a single value, but we do not know what.

The next race condition in Listing 6.5 occurs when global memory is set by every thread in the grid concurrently. The parameter result is stored in global memory. The line result[0] = i; is nonsense. For a start, the value of i was set with a race condition in shared memory. In essence, the programmer is no longer in control of these variables. The final value presented by these variables is completely up to the device. The device will schedule threads in some order and actually come up with an answer as shown in Figure 6.2, but it would very foolish to assume that the device will always return 831.

Figure 6.2: Output from Race Conditions

Read-Modify-Write

It may seem that if a shared variable was incremented by multiple threads instead of being set to multiple values as in Listing 6.5, the operation would be safe. After all, it is completely irrelevant what order the threads actually increment. So long as they all do increment, we should end up with the same value. The trouble is that this is still a race condition. To see why, we need to look in a little more detail at the increment instruction. The statement i++ actually does three things (this is applicable to both GPUs and CPUs):

- Read the value of i into a register.

- Increment the value in the register.

- Store the result back to i.

This process is called a read-modify-write operation. Almost all operations which modify memory (both in the host and the device) do so with these three steps. The GPU and indeed the CPU never operate directly on RAM. They are only able to operate on data if it is in a register. This is what the registers are for; they are the variables that a piece of hardware uses for its core calculations. This means the hardware must read the value from RAM first, and write the resulting value when the operation is complete. The trouble is that when more than one thread runs at the same time, they each do the read-modify-write simultaneously, jumbled up in any order, or both. 100 concurrent threads all trying to increment the same shared variable i might look like the following:

- All 100 threads read the value of i into registers.

- All 100 threads increment their register to 1.

- All 100 threads store 1 as the result.

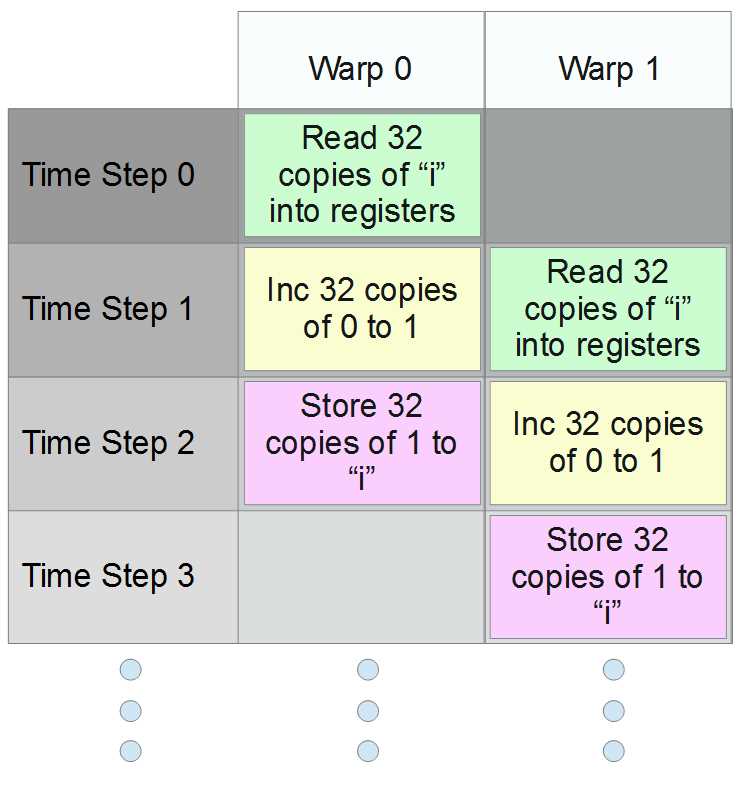

It is tempting to think that we will always get the value 1, but apart from being a very pointless use of 100 threads, this is not even true. The 100 threads may or may not actually operate in step with each other. In CUDA, threads are executed in warps of 32 threads at a time (a warp is a collection of 32 threads with sequential threadIdx values, all from the same block, and all executing simultaneously). Figure 6.3 illustrates 64 threads running concurrently in two warps.

Figure 6.3: CUDA warps attempting to increment concurrently

In Figure 6.3, we see four time steps from 0 to 3 (these might be thought of as individual clock cycles). In the example, threads from the first warp (warp 0) first execute a read. As they increment i, threads from the second warp read the original value of i (which is still 0). The first 32 threads then write their resulting 1 to memory as the second warp increments. Finally, the second warp writes a 1 to memory as well.

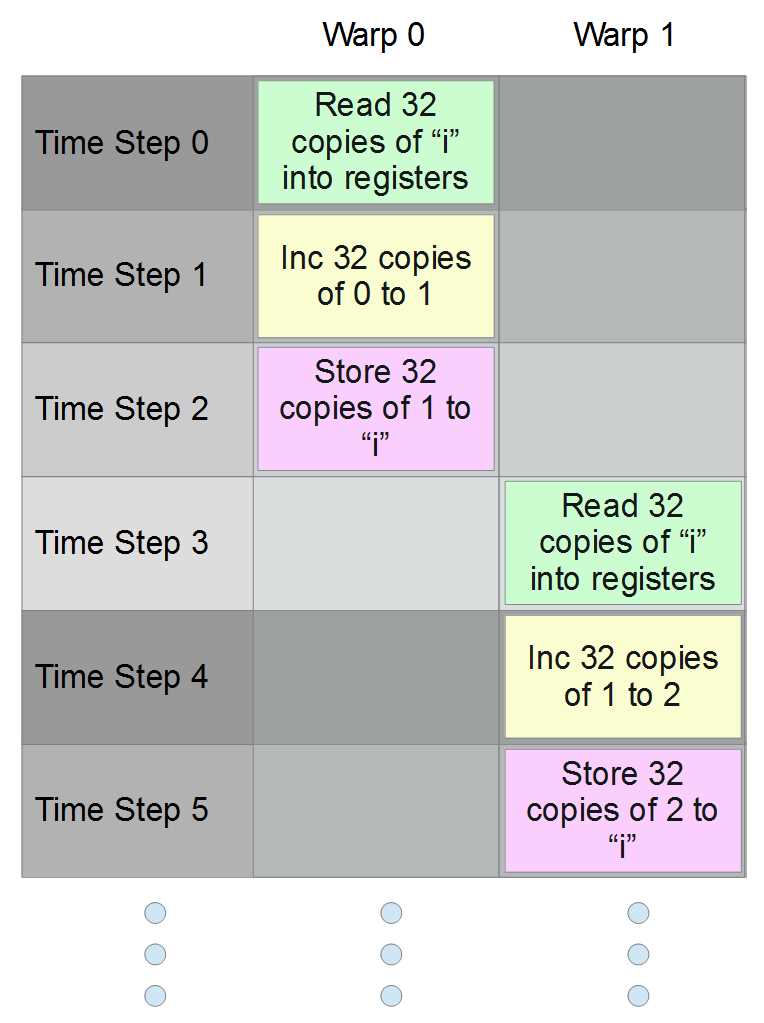

Figure 6.4: Another possible execution order

Figure 6.4 shows another possible way the scheduler might order two warps trying to increment a shared variable. In this example, the first warp completes the read-modify-write and the second warp increments the variable to 2. The scheduler might choose either of these execution orders when scheduling warps and it might choose other possibilities.

There is more than one possible output from the algorithm. Besides, if 32 threads are programmed to increment a variable, the programmer is probably hoping for an end result of 32, which they will almost certainly never get.

Note: There are special primitives for dealing with multiple threads when they share resources. Mutexes and semaphores are the most common. For those interested in these parallel primitives, I strongly recommend reading The Little Book of Semaphores by Robert Downey.

Block-Wide Barrier

A “barrier” in parallel programming is a point in the code where all threads must meet before any are able to proceed. It is a simple but extremely useful synchronization technique, which can be used to eliminate race conditions from code. In CUDA there is a block-wide barrier function, __syncthreads. The function takes no arguments and has no return value. It ensures that all threads of the block are synchronized at the point of the function call prior to proceeding. Using the __syncthreads function, we can ensure that threads do not race for a __shared__ variable. See Listing 6.6.

__global__ void SomeKernel() { // Declare shared variable __shared__ int i; // Set it to 0 i = 0; // Wait until all threads of the block are together __syncthreads(); // Allow one thread access to shared i if(threadIdx.x == 0) i++; // Wait until all threads of the block are together __syncthreads(); // Allow another single thread access to i if(threadIdx.x == 1) i++; } |

Listing 6.6: __syncthreads(), the block-wide barrier function

In the previous listing, __syncthreads is used to ensure that only one thread at a time increments the shared variable i. The initial setting of the variable to 0 by all threads is guaranteed to result in at least one of them successfully setting the value last. The next line contains a call to __syncthreads. The threads will all wait until every thread of the block has executed the i=0 instruction. Once all the threads have paused at the first __syncthreads call, only the thread with threadIdx.x == 0 will fall through the first if statement and find itself at another __syncthreads(). As they wait, the first thread (threadIdx.x == 0) will increment i and then join the other threads of the block waiting at the barrier. The threads will then proceed and the thread with threadIdx.x == 1 will increment i. The code shows that __syncthreads and single thread access to shared resources is a safe operation, and we are guaranteed that by the end of this code, the shared variable i will be incremented to 2.

Note: The __syncthreads() method is only a block-wide barrier. Threads that belong to other blocks will not be blocked. It is not useful for synchronizing access to global resources. Never use __syncthreads in situations where threads of a block branch. If some threads find a __syncthreads() in the code of an if statement while other threads of the same block fall through the if statement, it will produce a deadlock. The waiting threads will pause indefinitely, and will never see their brethren again, most likley causing the program to freeze.

Note: There is no safe way to produce a grid-wide barrier inside a kernel. The device is not designed to allow grid-wide barriers from within its own code. However, the host can cause grid-wide barriers. The function cudaMemcpy causes an implicit grid-wide barrier. The host will wait until the device has completed any executing kernels before the memory is copied. Also, the host function cudaDeviceSynchronize() is designed to explicitly allow the host to wait for the device to finish executing a kernel.

Atomic Instructions

Aside from barriers, threads can be made to safely access resources by using atomic instructions. An atomic instruction is one that performs the read-modify-write in a single, uninterruptable step. If 32 threads perform an atomic increment concurrently, the variable is guaranteed to be incremented 32 times. See Listing 6.7 for an example of using the atomicAdd instruction to increment a global variable.

Note: Atomic instructions are only available on devices with compute capability 1.1 or higher. To compile the code in Listing 6.7, you will need to specify compute_11,sm_11 or higher in the Code Generation option of your project.

|

#include <cuda.h> #include <cuda_runtime.h> using namespace std; __global__ void AtomicAdd(int* result) { // Atomically add 1 to result[0] atomicAdd(&result[0], 1); } int main() { int answer = 0; int* d_answer; // Allocate data and set to 0 cudaMalloc(&d_answer, sizeof(int)); cudaMemset(d_answer, 0, sizeof(int)); // Run 2048 threads AtomicAdd<<<64, 32>>>(d_answer); // Copy result and print to screen cudaMemcpy(&answer, d_answer, sizeof(int), cudaMemcpyDeviceToHost); cout<<"The result was "<<answer<<endl; return 0; } |

Listing 6.7: Atomically incrementing a global variable

The result from Listing 6.7 (the host’s answer variable) is always 2048. Every thread increments the global variable result[0] atomically, guaranteeing that its increment is complete before any other thread is allowed access to result[0]. The kernel was launched with 2048 threads, so the result will be 2048. When a thread begins an atomic read-modify-write of the result[0] variable, all other threads will have to wait until it has finished. The threads will each increment results[0] one at a time.

Atomic instructions are slow but safe. Many common instructions have atomic versions. For a complete list of the atomic instructions available, see the Atomic Functions section of the CUDA C Programming guide: http://docs.nvidia.com/cuda/cuda-c-programming-guide/index.html#atomic-functions.

Note: Devices with compute capability 2.0 and higher are able to perform atomic instructions on shared memory. Older devices (compute capability 1.xx) had atomic instructions for global memory only.

Shared Memory Banks and Conflicts

Now that we have examined some of the common problems in sharing resources between concurrent threads, we can turn our attention back to shared memory, and in particular how to use it efficiently. The device performs all operations (adding, multiplication, Boolean operations, etc.) on data in registers. Shared memory must be read into registers before it is operated on (global, texture, constant, and all other memories must also be read into registers first). Once a calculation is performed in the registers, the results can be stored back into shared memory. Shared memory is organized into words of four bytes each. Any four-byte word could hold a single 32-bit int, a float, half a double, two short ints, and any other possible combinations of 32 bits. Each word belongs to one of 32 banks, which read and write values to and from the registers.

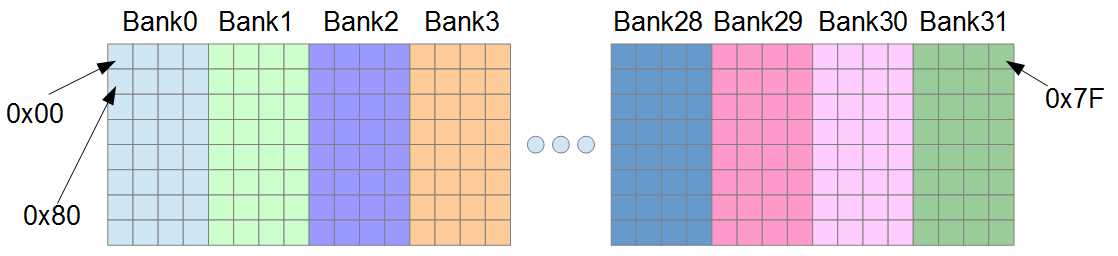

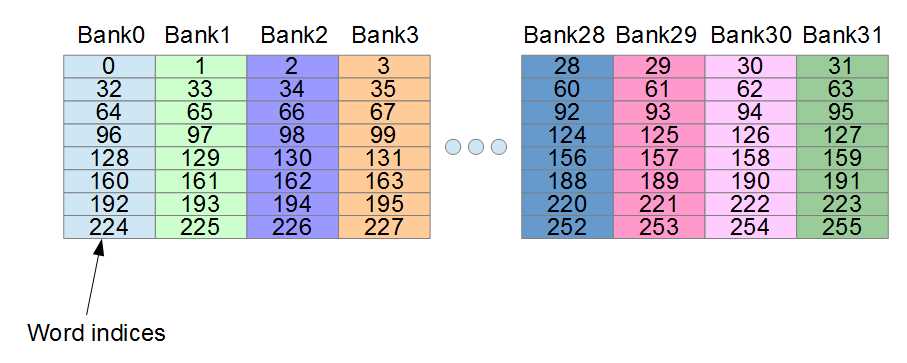

Figure 6.5: Addresses in Shared Memory

Figure 6.5 illustrates some of the addresses in shared memory. Bank0 is responsible for reading and writing the first four bytes of shared memory, and Bank1 reads and writes the next. Bank31 reads and writes bytes with addresses 0x7C to 0x7F, and after this point, the banks repeat. Bytes at addresses 0x80 to 0x83 belong to Bank0 again (they are the second word of Bank0).

Shared memory can be addressed as bytes, but it is also specifically designed to allow very fast addressing of 32-bit words. Imagine that we have an array in shared memory comprised of floats (floats are 32 bits wide or one word each):

__shared__ float arr[256];

Each successive float in the array will belong to a different bank until arr[32], which (like arr[0]) belongs to Bank0. Figure 6.5 illustrates the indices of these words and which banks they belong to.

Figure 6.6: Word indices in shared memory

This is important because each bank can only serve a single word to a warp at once. All 32 banks can simultaneously serve all 32 threads of a warp extremely quickly, but only if a single word is requested from each bank. When a warp requests some pattern of addresses from shared memory, the addresses correspond to any permutation whatsoever of the banks. Some permutations are much faster than others. When more than one word is requested from any single bank by the threads of a warp, it is said to cause a bank conflict. The bank will access the words in serial, meaning first one, and then the other.

Note: Bank conflicts are only a consideration at the warp level; any inter-block access patterns do not cause bank conflicts. There is no bank conflict if block0's warp accesses word0 from Bank0 at the same time that block1 accesses word1 from Bank0.

When all threads of a warp access exactly the same word from shared memory, an operation called broadcast is performed. Shared memory is read once and the value is divvied out to the threads of a warp. Broadcast is very fast—the same as reading from every bank with no conflicts.

On devices of compute capability 2.0 and up, there is an operation similar to a broadcast (but more flexible) called a multicast. Any time more than one thread of a warp accesses exactly the same word from any particular bank, the bank will read shared memory once and give the value to any threads that require it. The multicast is similar to the broadcast, only all 32 threads of the warp need not access the same word. If there are no bank conflicts, a multicast operates at the same speed as a broadcast operation.

Access Patterns

In the previous discussion on bank conflicts, broadcasts and multicasts have important implications for performance coding. There are many access patterns the threads of a warp could potentially request from shared memory. Some are much faster than others. All of the following examples are based on an array of words called arr[].

The following table shows a handful of patterns, the speed one might expect from employing them, and a description of conflicts that may be caused.

Table 6.2: Access Patterns

Access Pattern | Notes |

|---|---|

arr[0] | Fast, this is a broadcast. |

arr[blockIdx.x] | Fast, this is a broadcast. |

arr[threadIdx.x] | Fast, all threads request from different banks. |

arr[threadIdx.x/2] | Fast, this is a multicast. Every 2nd thread reads from the same bank. |

arr[threadIdx+71] | Fast, all threads request from different banks. |

arr[threadIdx.x*2] | Slow, 2-way bank conflict. |

arr[threadIdx.x*3] | Fast, all threads request from different banks. |

arr[threadIdx.x*8] | Very slow, 8-way bank conflict. |

arr[threadIdx.x*128] | Extremely slow, 32-way bank conflict. |

arr[threadIdx.x*129] | Fast, all threads request from different banks. |

Accessing multiples of threadIdx.x is analogous (produces the same address patterns) to accessing structures in an array. For instance, the following structure is exactly four words long.

// 4-word-long structure struct Point4D { float x, y, z, w; }; |

Listing 6.8: Structure of four words in length

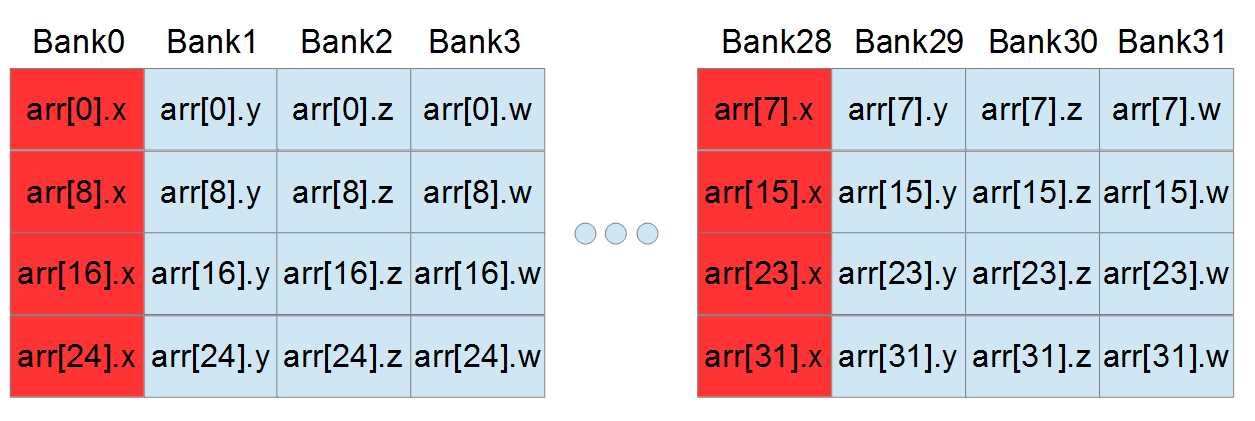

Given an array of instances of this structure in a kernel, and given that the threads are accessing subsequent elements based on their threadIdx.x, we will get a four-way bank conflict from the operation in Listing 6.9.

__shared__ Point4D arr[32]; arr[threadIdx.x].x++; // Four-way bank conflict |

Listing 6.9: Four-Way Bank Conflict

The increment of the x element requires three instructions (read-modify-write) and causes not one, but two four-way bank conflicts. The elements of the array are each four words long. The structures each have their x values four banks apart. Every fourth bank is serving the warp four values and the intermediate banks (Banks 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7 etc.) are not doing anything. See Figure 6.7.

Figure 6.7: Four-way bank conflict from structures

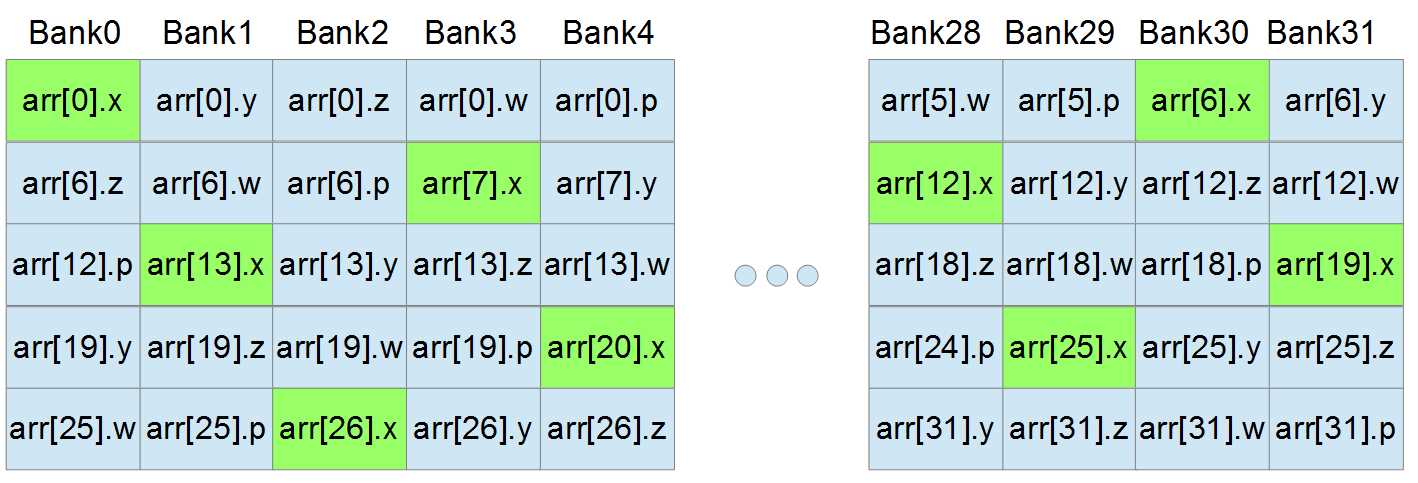

There is a very simple solution to this four-way bank conflict—pad the structure with an extra word, as shown in Listing 6.10.

// 4-word-long structure with extra padding struct Point4D { float x, y, z, w; float padding; }; |

Listing 6.10: Structure padded to offset banks

By adding an extra word, the sizeof(Point4D) has gone from four words to five, but the access pattern from the threads of a warp no longer causes any bank conflicts (at least not when each thread accesses a subsequent element of the array). With exactly the same code as before (Listing 6.9), we now see that, thanks to the extra padding, there are no bank conflicts at all—every thread is requesting a single word from a different bank.

Figure 6.8: Access pattern with padding word

The access pattern in Figure 6.8 looks a lot more complicated than the one from Figure 6.7, but it is much faster because every bank is going to be used exactly once.

Adding padding to offset the requested words and better utilize the 32 banks is often an excellent idea, but not always. It requires enough shared memory to store the extra padding word. The padding word is often completely useless other than to offset the request pattern. There are times when adding padding will be beneficial, and other times when shared memory is too valuable a resource to simply throw away 4 bytes of padding at every thread that wants it.

It is difficult (if not impossible) to entirely invent the best access patterns and padded structures using theory alone. The only way to fine-tune a shared memory access pattern is trial and error. The theory, and even the profiler, can only offer suggestions.

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.