CHAPTER 10

CUDA Libraries

The CUDA toolkit comes with a powerful collection of libraries, meaning you do not need to code your own versions to satisfy many common problems. In this chapter we will examine two of these libraries in detail. Even if your only interest is to learn efficient code, it's worth getting to know the other libraries.

Libraries: Brief Description

The following list briefly describes some of the libraries that are installed with the CUDA toolkit. These libraries are all of a very high quality, and are optimized, well tested, and generally very simple to use. These libraries are actively updated, and each new version of the CUDA toolkit usually includes newer versions of each of these libraries.

CUFFT—CUDA Fast Fourier Transform. This is a CUDA-accelerated implementation of the fast Fourier transform algorithm, which is extremely important in countless fields of study.

CUBLAS—CUDA Basic Linear Algebra Subprograms. This is a CUDA implementation of the popular BLAS library.

CUSPARSE—This library contains CUDA-accelerated algorithms for working with sparse and dense vectors and matrices.

NPP—NVIDIA Performance Primitives. This library presently contains implementations of several algorithms for working with video and image data and some signal processing functions. It is designed to closely resemble the Intel Integrated Performance Primitives library, but it is not currently a complete implementation.

CURAND—CUDA Random Number Generation. This library contains implementations of many strong and efficient random number generators, which are accelerated by CUDA. We will look at the CURAND library in some detail in examples later in this chapter.

Thrust—Thrust is a template library using parallel algorithms and data structures. It is designed as a CUDA-accelerated implementation of the Standard Template Library (STL), which is familiar to most C++ programmers. We will look at Thrust in some detail later in this chapter.

Others—There are countless libraries available online, and the collection is constantly expanding and being updated. For additional libraries, check out https://developer.nvidia.com/gpu-accelerated-libraries. The NVIDIA website does not offer an exhaustive list but libraries mentioned on the website tend to be of a very high quality.

We will now examine two of the previously mentioned libraries with a little more detail: CURAND and Thrust. The implementation and use of the other libraries (either those mentioned in the previous list or any of the countless libraries) is often similar to CURAND and/or Thrust. The following sections are intended to be a general introduction to using CUDA accelerated libraries with CURAND and Thrust as examples.

CUDA Random Number Generation Library (CURAND)

CURAND is a CUDA-accelerated collection of pseudo-random number generators. It includes a multitude of different generators, most of which generate extremely high quality random numbers, the sequences of which have very long periods. The library is useful for two reasons: it is able to generate sets of random numbers very quickly because it is CUDA accelerated, but also it contains special generators that are designed to generate random numbers on the fly in device code.

Host and Device APIs

The beauty of the CURAND library is that it is not only useful for quickly generating blocks of random numbers for consumption by the device (or the host), but it can also generate numbers in kernel code. There are two APIs included; one (the host API) is designed to generate random numbers with the host and store the resulting sequence in global memory (or system memory). The host can then call a kernel, passing the block of random numbers as a parameter for consumption by the device, or the block of random numbers can be consumed by the host. The other API (the kernel or device API) is designed to generate random numbers on the fly within kernels for immediate consumption by CUDA threads.

To use the CURAND library functions you must include the curand.h header in your project and link to the curand.lib library file in your project's properties. To include the various header and libraries in your project, look in the same folders as you did previously, and find curand.h and curand.lib. If they are there and you set your paths up correctly at the beginning of the book, then you should be able to just #include the headers where needed, and add the .lib to your linker list as you did with cudart.lib.

The curand.h header is the header for the host API. Additionally, you can include the curand_kernel.h header to use the device API, which we will examine shortly.

Host API

The host API can be used to generate blocks of random numbers in the device's global memory or in system memory. The following code listing (Listing 10.1) generates two blocks of random numbers using the host API: one in global memory and one in system memory. The host API can be used without the CUDA build customization and in a standard .cpp, instead of .cu files. The following code (Listing 10.1) was created as a new project. This section is not meant as a continuation of what we have previously coded, but is a completely new example project.

|

#include <iostream> #include <ctime> // For seeding with time(NULL) #include <cuda.h> #include <curand.h> // CURAND host API header using namespace std; int main() { // Count of numbers to generate const int count = 20; // Device generator stores in device global memory curandGenerator_t deviceGenerator; // Host generators store in system RAM curandGenerator_t hostGenerator; // Define device pointer for storing deviceGenerator results float *d_deviceOutput; // Define host arrays for storing hostGenerator's results float h_deviceOutput[count], hostOutput[count]; // Allocate memory on device for deviceGenerator cudaMalloc(&d_deviceOutput, sizeof(float)*count); // Initialize the two generators curandCreateGenerator(&deviceGenerator, CURAND_RNG_PSEUDO_DEFAULT); curandCreateGeneratorHost(&hostGenerator, CURAND_RNG_PSEUDO_DEFAULT); // Set the seed for both generators to 0. Using the same seed will // cause both generators create exactly the same sequence. curandSetPseudoRandomGeneratorSeed(deviceGenerator, 0); curandSetPseudoRandomGeneratorSeed(hostGenerator, 0); // If you would like the generators to use an unpredictable seed and // create different sequences, you can use time(NULL) as the seed. // Alter the value in some way (I've multiplied my hostGenerators by 10 // in the following) otherwise time(NULL) will be exactly the same when // you seed them. // curandSetPseudoRandomGeneratorSeed(deviceGenerator, time(NULL)); // curandSetPseudoRandomGeneratorSeed(hostGenerator, time(NULL)*10); // Generate a random block of uniform floats with both generators: // The deviceGenerator outputs to global memory: curandGenerateUniform(deviceGenerator, d_deviceOutput, count); // The hostGenerator's output is in system RAM curandGenerateUniform(hostGenerator, hostOutput, count); // Copy the device results to the host cudaMemcpy(h_deviceOutput, d_deviceOutput, sizeof(float)*count, cudaMemcpyDeviceToHost); // Free device and CURAND resources cudaFree(d_deviceOutput); curandDestroyGenerator(deviceGenerator); curandDestroyGenerator(hostGenerator); // Print out the generator sequences for comparison for(int i = 0; i < count; i++) { cout<<i<<". Device generated "<<h_deviceOutput[i]<< " Host generated "<<hostOutput[i]<<endl; } return 0; } |

Listing 10.1: CURAND Host API

Listing 10.1 generates two blocks of 20 random, floating point values. There are two types of generators in Listing 10.1: host and device (not to be confused with the two APIs). Both of these generators belong to the host API, and the device API generates its values inside kernels. The difference between the two generators is that the host generator (hostGenerator) stores the resulting sequence in system RAM, while the device generator (deviceGenerator) stores the sequence in global memory. The two generators in the previous listing should generate exactly the same values for their blocks of random floats, because they use the same seed. In fact, every time the program is executed, the generators will generate exactly the same sequences of numbers. If you comment out the lines that seed the generators to 0, and uncomment the lines that seed to time(NULL), you should find that the generators generate different numbers from each other, and different values each time the program is executed.

Note: You need not include the cuda.h header because the CUDA API is already included in the curand.h header. Likewise, the time(NULL) function can be called without the inclusion of the ctime header. These headers were included for clarity.

To generate random numbers with the CURAND library, you first need to create generator handles.

You can create a host generator with curandCreateGeneratorHost or a device generator with curandCreateGenerator. The first parameter to each of these functions is a curandGenerator_t, which will be passed to subsequent CURAND function calls as a generator handle.

The second parameter is the type of random number generator to use. There are many different algorithms for generating random numbers with computers, and the list of random generators changes with each generation of this library. To see the full list of algorithms included in the version of the CURAND library you have installed, right-click on the CURAND_RNG_PSEUDO_DEFAULT identifier and select Go to definition from the context menu in Visual Studio, or search for the file CURAND.h and examine its contents.

The d_deviceOutput pointer is a device pointer to data in the device’s global memory. After the sequence is generated, this pointer could be passed to a kernel for consumption. In Listing 10.1, it is copied back to the host and printed to the screen to be compared with the host’s generated values.

Tip: When using the host API for consumption by the device, it is best to generate the numbers as infrequently as possible. The numbers should be generated once prior to a kernel call. It would be very slow to jump back and forth between the host and device while the host generates new numbers in the middle of an algorithm.

Uniformly Distributed Generation

A uniformly distributed random float is one that lies between 0.0f and 1.0f. In theory, every possible value between these points is as likely as any other to be generated in the sequence. In reality there are an infinite number of real values between any two real numbers, but in computing there are around 224 different floats between 0.0f and 1.0f.

Tip: Random numbers in any range can be created from a set of random normalized numbers (such as those generated by curandGenerateUniform). For instance, to convert the sequences from Listing 10.1 into random floats between 100.0f and 150.0f, you could multiply each by 50.0f (the difference between the lowest value and the highest, 150.0f–100.0f) and add 100.0f. Be aware that the curandGenerateUniform function generates from 0.0f to 1.0f, but 0.0f is not included, and 1.0f is.

Normally Distributed Generation

Sometimes we need to generate numbers with a normal distribution. This means the values most likely to be generated will be those closest to the mean. Numbers further away from the mean have a decreasing likelihood of being generated, and the frequency of numbers when plotted will look like the familiar bell curve of a normal distribution.

In a normal distribution any number is possible, but the chances of generating numbers far from the mean (in standard scores) becomes very small very quickly. Use the curandGenerateNormal function to generate numbers based on a normal curve. The function requires a mean and a standard deviation value to describe the fall off and magnitude of the curve from which to generate numbers. For instance, replace the call to curandGenerateUniform in the previous code with a call to curandGenerateNormal based on the standard normal curve (this a normal curve with mean 0.0f and standard deviation of 1.0f) as per Listing 10.2.

// Generate a random block of floats from normal curves curandGenerateNormal(deviceGenerator, d_deviceOutput, count, 0.0f, 1.0f); curandGenerateNormal(hostGenerator, hostOutput, count, 0.0f, 1.0f); |

Listing 10.2: Generating numbers from normal curves

You will see that the numbers generated tend towards 0.0f (the mean of our normal curve and 4th parameter of the curandGenerateNormal function), but that several are 1.0f or more away from this mean. Most (theoretically 68.2 percent) of the numbers generated will be within -1.0f and 1.0f because we supplied 1.0f as our standard deviation (the 5th parameter of the curandGenerateNormal function) and 0.0f is the middle of -1.0 and 1.0. Using the values 0.0f for the mean and 1.0f for the standard deviation means the number will be generated from a standard normal curve.

Device API

The device API allows for the generation of random values within a kernel, without leaving the device. The device API is a little more complicated than the host API because it needs to set up and maintain the states of multiple generators (one for each thread). Include the curand_kernel.h header in your project files to use the device API and, as with the host API, link to the curand.lib library in your project's properties. The generation occurs within kernels, so (unlike the host API) you will need to use the CUDA Build Customization to launch kernels and store the code in a .cu file. Examine the code in Listing 10.3, in particular the InitRandGenerator and Generate kernels. Again, this code is intended as a new project; it does not build on anything we have previously coded.

|

#include <iostream> #include <cuda.h> #include <curand_kernel.h> #include <device_launch_parameters.h> using namespace std; // Kernel to init random generator states __global__ void InitRandGenerator(curandStateMRG32k3a *state) { int id = threadIdx.x + blockIdx.x * blockDim.x; // Init the seed for this thread curand_init(0, id, 0, &state[id]); } // Generate random numbers using the device API __global__ void Generate(unsigned int *result, int count, curandStateMRG32k3a *state) { int idx = threadIdx.x + blockIdx.x * blockDim.x; // Make a local copy of the state curandStateMRG32k3a localState = state[idx]; // Generate one number per thread if(idx < count) { // The numbers generated will be integers between 0 and 100 result[idx] = (unsigned int) curand(&localState)%100; } } int main() { // How many numbers to generate const int count = 100; // Declare the arrays to hold the results unsigned int* h_a = new unsigned int[count]; unsigned int* d_a; cudaMalloc(&d_a, sizeof(unsigned int)*count); // Declare the array to hold the state of the generator curandStateMRG32k3a *generatorState; cudaMalloc(&generatorState, sizeof(curandStateMRG32k3a) * count); // Call an init kernel to set up the state InitRandGenerator<<<(count/64)+1, 64>>>(generatorState); // Call a kernel to generate the random numbers Generate<<<(count/64)+1, 64>>>(d_a, count, generatorState); // Copy the results back to the host cudaMemcpy(h_a, d_a, sizeof(unsigned int)*count, cudaMemcpyDeviceToHost); // Print the results to the screen for(int i = 0; i < count; i++) cout<<i<<". "<<h_a[i]<<endl; // Free resources cudaFree(d_a); cudaFree(generatorState); delete[] h_a; return 0; } |

Listing 10.3: CURAND Device API

Listing 10.3 generates 100 random unsigned ints using the CURAND device API. It stores the numbers in global memory before copying them to the host and printing them out. The important thing to remember here is that the generated numbers can be consumed immediately in the kernel’s code; I have copied them back purely for purposes of demonstration.

An area of device memory needs to be allocated to hold the state of the generator; this can be done using cudaMalloc. I selected the curandStateMRG32k3a state, which will use a multiple recursive generator algorithm (this is the CUDA version of the MRG32k3a algorithm available in the Intel MKL Vector Statistical Library).

The seed and current position of the numbers generated so far for each thread must be known prior to generating subsequent random numbers. This state maintains this information.

Each thread sets up its own seed based on the threadIdx by calling the curand_init device function (in the InitRandGenerator kernel).

Since threadIdx.x is calculated to be unique within this grid, each thread will generate a different seed. Once the state has been seeded, the threads can generate a random number by calling curand. The curand function returns the next sequence of 32 bits from the state for each thread. We can take the remainder after division with the modulus operator to get a number within a certain range (in Listing 10.3 the numbers will range from 0 to 99 because of the %100).

The line curandStateMRG32k3a localState = state[idx]; creates a local copy of the state for each thread. It makes no difference to the performance of Listing 10.3, but if your kernel generates many numbers per thread, it will be quicker to use a local copy. Creating a local copy means that we do not need to use array subscripts, which are slower.

Tip: Creating generators is a slow process and they should, if possible, be created once and reused to avoid the overhead of setting up the states each time.

Thrust

The second library we will look at in detail is the Thrust library. The Thrust library is a CUDA-accelerated version of the Standard Template Library (STL) for C++. The library provides data types and common algorithms optimized with CUDA.

Tip: Many of the identifiers included in the Thrust library have the same names as those from the STL. When mixing Thrust and STL code it may be helpful to avoid using the using directive to include the entire namespaces. Instead, qualify references fully. For instance, use std::sort and thrust::sort.

There are two different types of basic vectors included in the Thrust library: host_vector and the device_vector. Host vectors are stored in system memory and controlled by the host, while device vectors are stored in device memory and controlled by the device.

The Thrust headers are located in the thrust subdirectory of the main CUDA toolkit headers directory. To use host or device vectors in your code, include the appropriate header, thrust\host_vector.h or thrust\device_vector.h.

Thrust does not have its own library (i.e. there is no thrust.lib like there was for CURAND). But it does use the standard CUDA Runtime library, so make sure your project links to CUDART.lib before using Thrust.

Basic Vector Manipulations

To define a Thrust vector, use thrust::host_vector<type> or thrust::device_vector<type> where type is the data type for the vector. There are various constructors you can use to initialize the vectors, including defining the size and initial values for each of the elements in the vector. Listing 10.4 shows some basic examples of defining vectors, accessing elements, and copying data to and from the various vector library types.

|

#include <iostream> #include <thrust\host_vector.h> #include <thrust\device_vector.h> #include <vector> // STL vector header int main() { // Defining vectors // STL vector, 100 ints set to 18 std::vector<int> stdV(100, 18); // Host vector of 100 floats thrust::host_vector<float> h(100); // Host vector, 100 ints set to 67 thrust::host_vector<int> hi(100, 67); // Empty device vector of doubles thrust::device_vector<double> dbv; // Device vector, 100 ints set to 0 thrust::device_vector<int> di(100, 0); // // Adding and removing elements // // Print initial element count for h std::cout<<"H contains "<<h.size()<<" elements"<<std::endl; // Remove last element h.pop_back(); std::cout<<"H contains "<<h.size()<<" elements"<<std::endl; // Adding and removing elements from device vector is the same dbv.push_back(0.5); std::cout<<"Final elements of dbv is "<<dbv.back()<<std::endl; dbv.pop_back(); // // Copying data between vectors // // Print out the first element of h std::cout<<"First element of hi is "<<hi[0]<<std::endl; // Copying host vector to device vector di = hi; std::cout<<"First element of di is "<<di[0]<<std::endl; // Copy from STD vector to device vector di = stdV; std::cout<<"First element of di is "<<di[0]<<std::endl; return 0; } |

Listing 10.4: Basic Vector Manipulations

Listing 10.4 shows that vectors can be copied from host to device and even STL vectors using the equal operator, =. Copying to or from a device vector uses cudaMalloc behind the scenes. Bear this in mind when coding with Thrust, or code can drop dramatically in performance, especially when performing many small copies.

Elements can be accessed using the array subscript operators [ ]. The standard STL vector manipulations like push_back, pop_back, and back (and many others) are all available for Thrust vectors. Vectors local to a function, device and host, are disposed of automatically when the function returns.

Sorting with Thrust

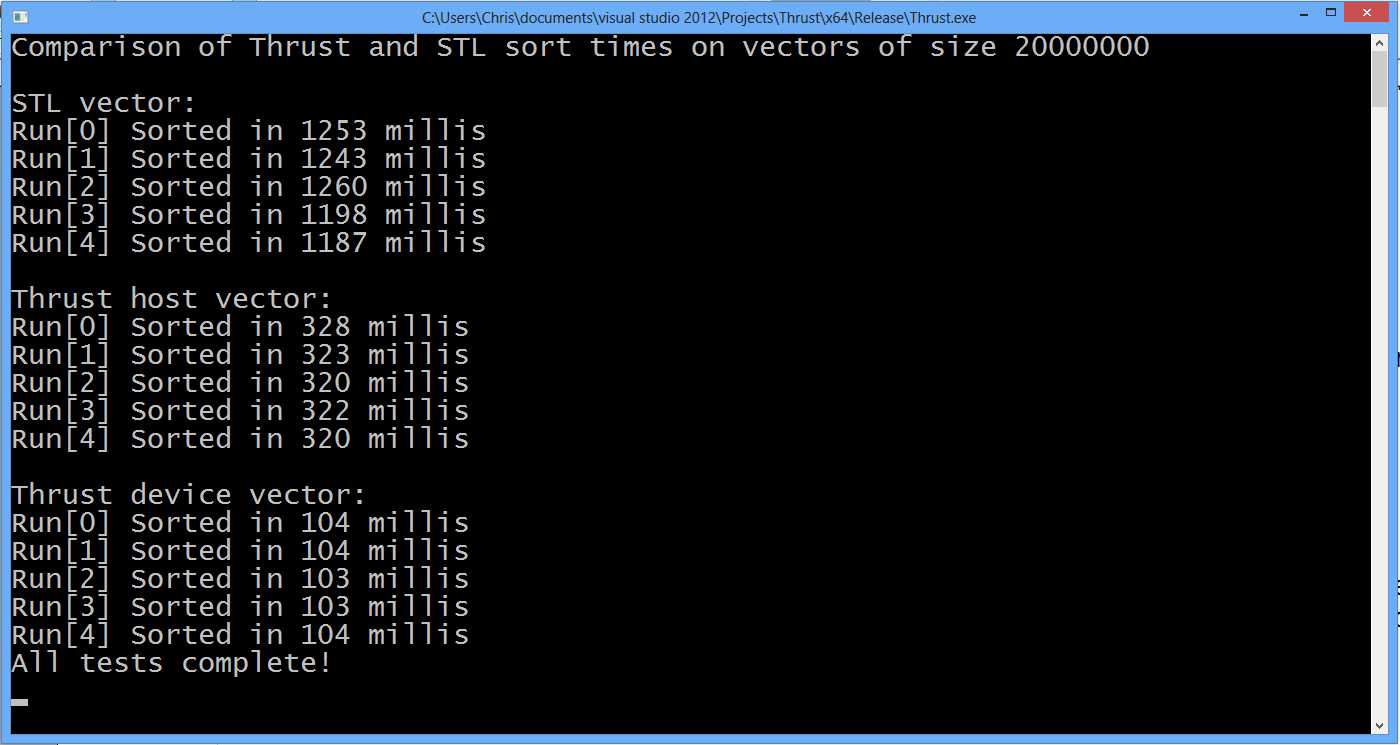

Listing 10.5 shows an example of how to use the sorting algorithm available in Thrust. It creates and sorts three lists of 20,000,000 integers. One is sorted using STL, one is a Thrust host vector, and the final one is a Thrust device vector. Each vector type sorts the integers five times, regenerating a random list between sorts. Note that, in this example, the device vector does not actually generate the random numbers, but copies them from the host vector.

|

// Standard headers #include <iostream> #include <ctime> // CUDA and Thrust headers #include <thrust\host_vector.h> #include <thrust\device_vector.h> #include <thrust\sort.h> // STL headers #include <vector> #include <algorithm> // Helper defines and variable for timing long startTime; #define StartTimer() startTime=clock() #define ElapsedTime (clock()-startTime) int main() { int count = 20000000; // 20 million elements to sort // Vectors std::vector<int> stlVec(count); // STL vector thrust::host_vector<int> hostVec(count); // Thrust host vector thrust::device_vector<int> devVec(count); // Thrust device vector std::cout<<"Comparison of Thrust and STL sort times on vectors of size "<< count<<"\n\n"; // Sort 5 times using STL vector std::cout<<"STL vector:"<<std::endl; for(int i = 0; i < 5; i++) { std::generate(stlVec.begin(), stlVec.end(), rand); StartTimer(); std::sort(stlVec.begin(), stlVec.end()); std::cout<<"Run["<<i<<"] Sorted in "<<ElapsedTime<<" millis"<< std::endl; } // Sort 5 times using Thrust host vector std::cout<<"\nThrust host vector:"<<std::endl; for(int i = 0; i < 5; i++) { thrust::generate(hostVec.begin(), hostVec.end(), rand); StartTimer(); thrust::sort(hostVec.begin(), hostVec.end()); std::cout<<"Run["<<i<<"] Sorted in "<<ElapsedTime<<" millis"<< std::endl; } // Sort 5 times using Thrust device vector std::cout<<"\nThrust device vector:"<<std::endl; for(int i = 0; i < 5; i++) { // Host generates values for devVec thrust::generate(hostVec.begin(),hostVec.end(),rand); devVec = hostVec; // Copy from host since there's no rand() StartTimer(); thrust::sort(devVec.begin(), devVec.end()); std::cout<<"Run["<<i<<"] Sorted in "<<ElapsedTime<<" millis"<< std::endl; } std::cout<<"All tests complete!"<<std::endl; return 0; } |

Listing 10.5: Vector Sorting Comparison

Figure 10.1: Example output from Listing 10.5

The Thrust device vector is clearly very fast (Figure 10.1 shows the device vector is around 10 times faster than STL and around 3 times faster than the host vector). What is perhaps surprising is that the host vector is considerably faster than the STL. When the lists are sorted already (or nearly), the STL sort has a special trick; it notices the elements are in order and quits the sort early. This gives the STL a peculiar advantage with nearly sorted lists. Placing the lines that regenerate the random list outside the for loops shows this. The STL sorts at around 168 milliseconds on the tested machine when the list is sorted.

Replacing all the calls to sort with stable_sort implements a stable sort. The indices of identical elements are guaranteed to maintain order with respect to one another through a stable sort. A stable sort slows the STL vector down while the Thrust vectors are relatively unaffected.

Transformations, Reductions, and Stream Compaction

As a final example, Listing 10.6 shows more of the Thrust library's abilities. It finds the factors of an integer up to its square root. This is a very inefficient method for factorizing integers (it is just a brute force search with a marvelously undesirable memory footprint), but it shows how to use several other important functions of the Thrust library.

The following code will not work on devices with compute capability 1.x. Remember to set the SM and compute values in your project to 2.0 or higher.

|

#include <iostream> // Thrust headers #include <thrust\device_vector.h> #include <thrust\transform.h> #include <thrust\sequence.h> #include <thrust\copy.h> // Helper function, returns true if x is zero // else return false struct isZero { __device__ bool operator()(const int x) { return x == 0; } }; int main() { int x = 600; // The integer to factorize // // Define Thrust device vectors // // dx vector will be filled with multiple copies of x thrust::device_vector<int> dx((int)(std::sqrt((double)x)+1)); // dy vector will be filled with sequence (2, 3, 4... etc.) thrust::device_vector<int> dy((int)(std::sqrt((double)x)+1)); // factors vector is used to store up to 20 factors thrust::device_vector<int> factors(20); // Fill dx with multiple copies of x thrust::fill(dx.begin(), dx.end(), x); // Fill dy with a sequence of integers from 2 up to // the square root of x thrust::sequence(dy.begin(), dy.end(), 2, 1); // Set elements of dx[] to remainders after division // of dx[] and dy[] thrust::transform(dx.begin(), dx.end(), dy.begin(), dx.begin(), thrust::modulus<int>()); // Multiply all remainders together int product = thrust::reduce(dx.begin(), dx.end(), 1, thrust::multiplies<int>()); // If this product is 0 we found factors! if(!product && x >= 4) { std::cout<<"Factors found!"<<std::endl; // Compact dx to factors where dy is 0 thrust::copy_if(dy.begin(), dy.end(), dx.begin(), factors.begin(), isZero()); // Print out the results for(int i = 0; i < factors.size(); i++) { if(factors[i] != 0) std::cout<<factors[i]<<" is a factor of "<< x<<std::endl; } } else { // Otherwise x is prime std::cout<<x<<" is prime, factors are 1 and "<<x<<std::endl; } return 0; } |

Listing 10.6: Factorizing Integers

After the headers in Listing 10.6, you will see the definition of a structure (isZero). The structure consists of a single Boolean function, which is used as a predicate later in the code.

Three vectors are used in the main method. dx and dy (nothing to do with calculus) are used as two temporary device storage vectors. dx holds multiple copies of the integer being factorized, which is the value of the variable x. dy holds all of the integers from 2 up to the square root of x.

To fill the dx vector with multiple copies of the x variable, the thrust::fill function is employed. It takes two iterators, which specify the start and end of the area to fill, and a third parameter, which is the value to fill with.

To create a list of all integers from 2 up to the square root of x and store them in the dy vector, I have used the thrust::sequence function. There are overloaded versions of sequence, but the version used here takes four parameters. The first two parameters are the start and end iterators for the area being filled. The third parameter is the value to start with, and the final parameter is the step or gap between the values generated.

The next step is to divide the xs stored in dx with the sequential integers in dy, taking the remainder with the modulus operator. In the code this is achieved with the thrust::transform function. Transforms perform the same operation on many elements of vectors. The transform function used in the code takes four parameters. The first two are the start and end iterators of the input. The next is the start iterator for the second input (modulus requires two operands). The third parameter is the output iterator to which the results will be stored, and the final parameter is the function to be performed between the elements of the dx and dy vectors. The result of this function call is that each of the xs in dx is divided by the corresponding element in dy, and the remainder after the division replaces the original values in dx.

The next function call is an example of using a thrust::reduce. A reduce algorithm (or parallel reduction) reduces the elements of a vector (or array or any other list) to a single value. It could, for instance, produce the sum of elements in an array, the standard deviation, average, or any other single value. In the code it is used to multiply all the elements of dx together. If any of them were 0, the result of this multiplication would be 0, which means we found factors (i.e. some integers were found that evenly divide x). If the result of this multiplication is not 0, it means none of the integers in dy are factors of x. If no integer from 2 to the square root of x is a factor of x, then x is prime.

The thrust::reduce function used here takes four parameters. The first two are the start and end iterators to the data that is to be reduced. The third parameter is the start value for the reduction. If you were summing a list of numbers you might use 0 for the initial value, but here we are multiplying, so I have used 1. The final parameter is the operation to use. I have used integer multiplication with thrust::multiplies<int>(). The resulting float (product) from this reduction is the product of all the elements in the dx vector. The reduction, as used here, is a complete waste of time, and it is only supplied for illustration of thrust::reduce.

The final task (if we found the factors and product was 0) is to copy the factors we found into another vector (the factors vector). To do this we want to copy elements from dy to factors where dx's elements are 0. It is a complicated operation to describe in English, but it is easily achieved by a call to thrust::copy_if. This operation is called a stream compaction. We are compacting the elements in dy to another vector based on some predicate (i.e. that the corresponding element in dx is 0). The function (thrust::copy_if) as used here takes five parameters; the first two are the start and end iterators of the stream being compacted, which is dy. The next is called the stencil parameter; it is the vector of the values to compare against the predicate. Here, we are checking if dx's values are 0, so the stencil is dx. The fourth parameter is the start iterator to store the results, factors.begin(). The final parameter is the predicate, a function returning bool, which decides which elements are copied and which are not.

The isZero() function was defined at the top of the application; it returns true when its parameter is 0 and false for any other values. This predicate (isZero) is a __device__ function. Every element in the dx vector will be passed through the predicate function concurrently; when the results are true, the corresponding elements of dy are copied to subsequent positions in factors. The end result of the stream compaction is that the factors of x will be stored in the factors vector, from which they are printed to the screen using a for loop and cout.

This has been a very quick look into some aspects of the Thrust library. Each of the categories of algorithm (transforms, reductions, and stream compactions) are far more flexible than this simple example illustrates. In addition, the Thrust library has a collection of very powerful and flexible iterators, which we have not looked at in these examples. For further reading on the topic of the Thrust library, consult the Thrust Quick Start Guide, which comes with the CUDA Toolkit. The exact path of the PDF documentation will differ for each version of the toolkit; the following is the default path for version 6.5:

C:\Program Files\NVIDIA GPU Computing Toolkit\CUDA\v6.5\doc\pdf\Thrust_Quick_Start_Guide.pdf

The Thrust Quick Start Guide is also available online from NVIDIA at http://docs.nvidia.com/cuda/thrust/index.html.

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.