CHAPTER 4

Writing Object-Oriented Code

C# is an object-oriented programming (OOP) language. It supports inheritance, encapsulation, polymorphism, and abstraction. This chapter shows you how C# supports OOP.

Implementing Inheritance

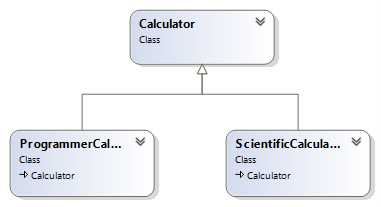

In C#, inheritance defines a relationship between two classes where a derived class can reuse members of a base class. A simple way to view this is that a derived class is a more specific version of a base class. We will reuse the calculator example from previous chapters, but alter it to provide two different types of calculators: scientific and programmer. Since they’re both calculators, it could be useful to create a relationship with a Calculator base class and ScientificCalculator and ProgrammerCalculator derived classes, like this:

- Calculator

- ScientificCalculator

- ProgrammerCalculator

In C#, you would express this relationship as follows.

public class Calculator { } public class ScientificCalculator : Calculator { } public class ProgrammerCalculator : Calculator { } |

As you can see, we added a colon suffix (as the inheritance operator) to the derived class and specified the base class it is derived from. The following figure illustrates the inheritance relationship between these classes.

Figure 1: Calculator Inheritance Diagram

You can assume that Calculator will have all of the standard operations like addition, subtraction, and more that all calculators have. The following code listing is an expanded example that shows the base class with a common method, and the derived classes with specialized methods that only belong to those classes.

using System; public class Calculator { public double Add(double num1, double num2) { return num1 + num2; } } public class ScientificCalculator : Calculator { public double Power(double num, double power) { return Math.Pow(num, power); } } public class ProgrammerCalculator : Calculator { public int Or(int num1, int num2) { return num1 | num2; } } |

The methods of the derived classes in the previous example used the FCL Math class for Power, which has many more math methods you can use in your own code, and also used the built-in C# | operator for Or. The following example shows how to write code that takes advantage of inheritance with the previous classes.

using System; public class Program { public static void Main() { ScientificCalculator sciCalc = new ScientificCalculator(); double powerResult = sciCalc.Power(2, 5); Console.WriteLine($"Scientific Calculator 2**5: {powerResult}"); double sciSum = sciCalc.Add(3, 3); Console.WriteLine($"Scientific Calculator 3 + 3: {sciSum}"); ProgrammerCalculator prgCalc = new ProgrammerCalculator(); double orResult = prgCalc.Or(5, 10); Console.WriteLine($"Programmer Calculator 5 | 10: {orResult}"); double prgSum = prgCalc.Add(3, 3); Console.WriteLine($"Programmer Calculator 3 + 3: {prgSum}"); Console.ReadKey(); } } |

Both the ScientificCalculator instance, sciCalc, and the ProgrammerCalculator instance, prgCalc, call the Add method. Further, those classes don’t define their own Add, but they do derive from Calculator and therefore inherit Calculator’s Add.

The ability to inherit isn’t always guaranteed; the next section explains more about when a class member is visible to other classes.

Access Modifiers and Encapsulation

In the previous example, all classes and methods had public modifiers, meaning that any other class or code can see and access them in code. You can leave off access modifiers and accept defaults. In that case, a class access becomes what is known as internal, and class members default to private.

Classes can only be internal or public. If they’re internal, they can only be accessed by code inside of the assembly they are contained in.

Available access modifiers for class members include public, private, internal, internal protected, and protected. The public and internal modifiers have the same meaning for class members as they do for classes.

The default modifier for class members, private, means that code outside the class can’t use that member; only other members within the same class can use it. This is useful if you want to modularize a method by breaking it into different supporting methods, but the supporting methods have no meaning outside of the class.

The protected modifier allows derived classes inside and outside the assembly to use the protected base class member. The internal protected modifier further restricts protected behavior only to derived classes inside the same assembly.

Most of the access modifier defaults and behaviors apply to struct types as well as classes, except for protected and internal protected, as I’ll explain next.

Designing Types: Class vs. Struct

A struct is another C# type that looks similar to a class, but has different behavior. A struct can’t derive from another class or struct. Since implementation inheritance doesn’t apply to a struct, neither do protected and internal protected modifiers. A struct does have interface inheritance, which I’ll explain more in the Exposing Interfaces section later in this chapter.

Additionally, a struct copies by value, as opposed to a class which copies by reference. The difference is that if you pass a struct instance to a method, the method gets a brand new copy of the struct value. If you copy a class instance to a method, the method gets a copy of a reference to the class in the heap, which is an area in computer memory that the CLR uses to allocate space for reference type objects. These facts help you decide whether you should design a type as a class or struct. Imagine a type with many properties and how it would hurt performance if you had to pass it by value to a method as a struct; the state of that type is copied to the stack, which is memory the CLR allocates for every method call to hold items like parameters and local variables. In that case, the proper design decision might be to define the type as a class so that only the reference is copied.

Most of the built-in types, such as int, double, and char, are value types. If you have a type with those semantics—small and a single value—then designing a type as a struct might be a benefit. Otherwise, designing a type as a class is fine. Here’s an example of a type that might make a good struct.

public struct Complex { public Complex(double real, double imaginary) { Real = real; Imaginary = imaginary; } public double Real { get; set; } public double Imaginary { get; set; } public static Complex operator +(Complex complex1, Complex complex2) { Complex complexSum = new Complex(); complexSum.Real = complex1.Real + complex2.Real; complexSum.Imaginary = complex1.Imaginary + complex2.Imaginary; return complexSum; } public static implicit operator Complex(double dbl) { Complex cmplx = new Complex(); cmplx.Real = dbl; return cmplx; } // This is not a safe operation. public static explicit operator double(Complex cmplx) { return cmplx.Real; } } |

Complex could make a good struct because you might have a lot of mathematical operations, and it would be more efficient to pass a copy of the numbers on the stack rather than letting the CLR allocate memory as it does for a class.

Complex has a constructor, named after the class itself, with a couple parameters. This makes it easy to initialize a new instance of Complex.

There are a few operator overloads in Complex: an addition operator and two conversion operators. The addition operator lets you add two complex numbers. Where the operator identifier (+) precedes the parameter list, the values to be added are specified in the parameters, and the return type is part of the signature. Operators are always static.

The two conversion operators let you make assignments between the containing type and another type of your choice. The type assigned to is the operator identifier and the type being assigned is the parameter. The implicit modifier means the conversion is safe and the explicit modifier means the conversion has the potential to lose data or provide an invalid result. For example, assigning a double to an int would be explicit because of loss of precision, and the explicit conversion in the previous example causes loss of the imaginary part of the number. The following code sample demonstrates how Complex could be used.

using System; class Program { static void Main() { Complex complex1 = new Complex(); complex1.Real = 3; complex1.Imaginary = 1; Complex complex2 = new Complex(7, 5); Complex complexSum = complex1 + complex2; Console.WriteLine( $"Complex sum - Real: {complexSum.Real}, " + $"Imaginary: {complexSum.Imaginary}"); Complex complex3 = 9; double realPart = (double)complex3; Console.ReadKey(); } } |

The Main method instantiates complex1 and then populates its values. Next, Main instantiates complex2 by using the Complex constructor, which is simpler initialization code.

You can also see how natural it is to use the addition operator, rather than an Add method used in previous Calculator demos.

Because there’s an implicit conversion from int to double and Complex has an implicit conversion operator from double to Complex, Main is able to assign 9 to complex3. The same can’t be said for assigning complex3 to realPart because Complex to double is an explicit conversion operator in the Complex type. Any time you have an explicit conversion, you must use a cast operator, as in (double)complex3.

One of the items you need to watch out for when working with value types is a concept referred to as boxing and unboxing. Boxing occurs any time you assign a value type to object, and unboxing occurs when you assign object to a value type. The following code demonstrates one scenario where this could happen.

ArrayList intCollection = new ArrayList(); intCollection.Add(7); int number = (int)intCollection[0]; |

An ArrayList is a collection class belonging to the System.Collections namespace. It is more powerful than an array and operates on type object. The Add method accepts an argument of type object. Since all types derive from object, an ArrayList is flexible enough to allow you to work with objects of any type. Boxing occurs when passing 7 to the Add method because 7 is an int (a value type) and is converted to object. What is really happening is that the CLR creates a boxed int in memory. Since the ArrayList holds type object, you also need to perform a conversion to unbox a value when reading from the ArrayList. The (int) cast operator converts from object (the boxed int) to int when reading the first element of intCollection.

The problem that boxing and unboxing cause is related to performance. In this situation, the reason you would use a collection is because you want to hold a lot of int values, which could be hundreds or thousands. Think about all the time spent accessing that ArrayList and incurring the performance penalty of boxing and unboxing on each operation.

Note: ArrayList is an old collection class that existed in C# v1.0 and is no longer used in modern development. C# v2.0 introduced generics, which use new collection classes that are strongly typed and avoid the boxing and unboxing penalties. While the ArrayList example is unlikely today, this scenario still highlights the performance penalty of any other situation where you might be assigning a value type to an object type.

Another difference between class (reference types) and struct (value types) is equality evaluation. Value type equality works by comparing the corresponding members of the struct. Reference type equality works by verifying that references are equal. In other words, structs are equal if their values match, but classes are equal if they reference the same object in memory. In the later section on polymorphism, you’ll learn how to override the object.Equals method to give you more control over class equality.

Creating Enums

An enum is a value type that lets you create a set of strongly typed mnemonic values. They’re useful when you have a finite set of values and don’t want to represent those values as strings or numbers. Here’s an example of an enum.

public enum MathOperation { Add, Subtract, Multiply, Divide } |

Like a struct, an enum is a value type. You use the enum keyword as the type definition. The previous enum is named MathOperation and has four members. The following example shows how you can use this enum.

using System; using static MathOperation; class Program { static void Main() { string[] possibleOperations = Enum.GetNames(typeof(MathOperation)); Console.Write($"Please select ({string.Join(", ", possibleOperations)}): "); string operationString = Console.ReadLine(); MathOperation selectedOperation; if (!Enum.TryParse<MathOperation>(operationString, out selectedOperation)) selectedOperation = MathOperation.Add; switch (selectedOperation) { case MathOperation.Add: Console.WriteLine($"You selected {nameof(Add)}"); break; case MathOperation.Subtract: Console.WriteLine($"You selected {nameof(Subtract)}"); break; case MathOperation.Multiply: Console.WriteLine($"You selected {nameof(Multiply)}"); break; case MathOperation.Divide: Console.WriteLine($"You selected {nameof(Divide)}"); break; } Console.ReadKey(); } } |

The FCL has an Enum class that lets you work with enums and the previous Main method shows how to use a couple of its methods. Enum.GetNames returns a string array, representing the names in the enum, specified with the typeof operator. The string.Join method, the expression in the interpolated string of the Console.WriteLine, creates a comma-separated string of these names.

The Enum.TryParse method in the previous example takes a string and produces an enum of the type specified in the type parameter, which is MathOperation in this case. The out parameter means that TryParse will return the parsed value in the selectedOperation variable. This is practical because the return type of the TryParse is bool, allowing you to know whether the input string, operationString, is valid.

The selectedOperation variable is of type MathOperation. The default syntax for enums is to prefix them with the enum type name, as in MathOperation.Add. However, you can also add a using static clause to the top of the file, allowing you to only specify the member name, as the previous example shows in the switch statement. A switch statement can operate on numbers, strings, or enums.

Enabling Polymorphism

Polymorphism lets derived classes specialize a base class implementation. The mechanism to allow polymorphism is to decorate a base class method with the virtual modifier and decorate the derived class method with the override modifier. If you were designing the Calculator class, you could allow derived classes to implement their own improved or specialized versions of the Add method, as shown in the following sample.

using System; public class Calculator { public virtual double Add(double num1, double num2) { Console.WriteLine("Calculator Add called."); return num1 + num2; } } public class ProgrammerCalculator : Calculator { public override double Add(double num1, double num2) { Console.WriteLine("ProgrammerCalculator Add called."); return MyMathLib.Add(num1, num2); } } public class MyMathLib { public static double Add(double num1, double num2) { return num1 + num2; } } public class ScientificCalculator : Calculator { public override double Add(double num1, double num2) { Console.WriteLine("ScientificCalculator Add called."); return base.Add(num1, num2); } } |

Polymorphism is opt-in for C#. Notice that the Add method in the base class Calculator has a virtual modifier. Polymorphism doesn’t occur unless a base class method has the virtual modifier. Also, notice that the derived classes ScientificCalculator and ProgrammerCalculator have override modifiers. Again, these methods won’t be called polymorphically unless they have the override modifier. Additionally, a method with the override modifier is also virtual for any of its derived classes.

With polymorphism, the overridden method in derived classes executes at runtime. If you wanted to call the base class implementation of that method, call the base class method with the base keyword. ScientificCalculator calls base.Add(num1, num2) to call the Add method in Calculator. Here’s an example of how this works.

using System; public class Program { public static void Main() { Calculator sciCalc = new ScientificCalculator(); double sciCalcResult = sciCalc.Add(2, 5); Console.WriteLine($"Scientific Calculator 2 + 5: {sciCalcResult}"); Calculator prgCalc = new ProgrammerCalculator(); double prgCalcResult = prgCalc.Add(5, 10); Console.WriteLine($"Programmer Calculator 5 + 10: {prgCalcResult}"); Console.ReadKey(); } } |

The output for this program would be:

ScientificCalculator Add called.

Calculator Add called.

Scientific Calculator 2 + 5: 7

ProgrammerCalculator Add called.

Programmer Calculator 5 + 10: 15

Main assigns instances of ScientificCalculator and ProgrammerCalculator to variables of type Calculator. As you saw in the previous listing, ScientificCalculator and ProgrammerCalculator are derived types and Calculator is their base type. The derived instances are the runtime type—the actual type when the program is running—and the base class is the compile-time type. The runtime-type overrides execute at runtime.

Looking at the definition of Add in ScientificCalculator, Calculator, and Main, and looking at the output, you can trace the polymorphic behavior of this program. Main calls Add on the ScientificCalculator instance. ScientificCalculator.Add executes because it overrides the virtual Calculator.Add method. After writing the first line of output, ScientificCalculator.Add calls the Calculator.Add method with the base keyword. Calculator.Add prints the second line to the output, performs the addition calculation, and returns the sum. ScientificCalculator.Add returns the return value from Calculator.Add. Main assigns the return value from ScientificCalculator.Add to the sciCalc variable and prints the results into the third line of the output. Tracing the call to ProgrammerCalculator.Add is similar, except that there is no call to the Calculator.Add in the base class.

Another example of when you would want to use polymorphism is in defining reference type equality. By default, reference types are only equal if their references are the same. The following example shows how to control reference type equality.

public class Customer { int id; string name; public Customer(int id, string name) { this.id = id; this.name = name; } public override bool Equals(object obj) { if (obj == null) return false; if (obj.GetType() != typeof(Customer)) return false; Customer cust = obj as Customer; return id == cust.id; } public static bool operator ==(Customer cust1, Customer cust2) { return cust1.Equals(cust2); } public static bool operator !=(Customer cust1, Customer cust2) { return !cust1.Equals(cust2); } public override int GetHashCode() { return id; } public override string ToString() { return $"{{ id: {id}, name: {name} }}"; } } |

Since all classes implicitly derive from object, they can override object virtual methods Equals, GetHashCode, and ToString. Customer overrides Equals. When you override Equals, check for null and type equality before working with the objects to prevent callers from accidentally comparing null or incompatible types. Customer instances are equal if they have the same id.

Customer has a constructor that initializes the state of the class. The this operator lets you access members of the containing instance and helps avoid ambiguity.

When implementing custom equality, you should also overload the equals and not equals and override the GetHashCode method. The default implementation of GetHashCode is a system-defined object id, so you could override this to achieve a better distribution of values in a hash.

Tip: You can escape { and } characters that you don’t want to evaluate as expressions by doubling them as {{ and }} respectively in string interpolation.

The following is an example of how to check equality of Customer instances.

using System; class Program { static void Main() { Customer cust1 = new Customer(1, "May"); Customer cust2 = new Customer(2, "Joe"); Console.WriteLine($"cust1 == cust2: {cust1 == cust2}"); Customer cust3 = new Customer(1, "May"); Console.WriteLine($"\ncust1 == cust3: {cust1 == cust3}"); Console.WriteLine($"cust1.Equals(cust3): {cust1.Equals(cust3)}"); Console.WriteLine($"object.ReferenceEquals(cust1, cust3): {object.ReferenceEquals(cust1, cust3)}"); Console.WriteLine($"\ncust1: {cust1}"); Console.WriteLine($"cust2: {cust2}"); Console.WriteLine($"cust3: {cust3}"); Console.ReadKey(); } } |

When using the == operator, the code calls the operator overload and Equals calls the equals method as expected. ReferenceEquals is an object method that is useful because it allows reference equality checking in case the type defined a custom Equals override.

If Customer had not overridden ToString, the last three Console.WriteLine statements in the previous code listing would have printed the type name, which is the default behavior of ToString.

Writing Abstract Classes

In previous examples, you could create an instance of Calculator. However, it may or may not make sense to instantiate a base class. A base class may serve only as a reusable type for common functionality of similar derived classes and to enable polymorphism, yet not have substance enough to be used on its own. In that case, you can modify the class definition as abstract, as shown in the following sample.

public abstract class Calculator { // ... } |

In an abstract class, you can have virtual or non-virtual members. Additionally, you can have abstract methods. An abstract method doesn’t have an implementation. Derived classes should specify the implementation and you don’t want a default implementation in the base class that might not make sense. The purpose of an abstract method is to specify an interface that derived classes must implement. In the case of Calculator, you could define an abstract Add method as shown in the following code example.

public abstract class Calculator { public abstract double Add(double num1, double num2); } |

The Add method has an abstract modifier. This method is implicitly virtual, but can’t be called by a derived class because it doesn’t have an implementation. The semicolon is required to terminate the abstract method signature. When an abstract class has abstract methods, all derived classes must override the abstract method. The Main method in the previous section still runs if you change the definition of the non-abstract Calculator class to the previous abstract Calculator.

Abstract classes are nice for situations where you want to have some default behavior, specify what the public interface of a class is, and support polymorphism. However, there are some limitations in that a C# class can have only one base class. Additionally, a struct can’t inherit another class or struct, so they don’t help if you need to write code that allows you to replace any number of value types with a base class implementation. There is an alternative, which I’ll discuss next.

Exposing Interfaces

If you only wanted a base class that specified an interface for a common set of operations, you could create an abstract class with only abstract methods. This ensures that all derived classes have those abstract methods. However, there’s a better alternative, named after what it does: an interface.

The benefit of the interface type is that both class and struct types can inherit multiple interfaces. You can also implement polymorphism with interfaces. They don’t have any implementation and you must write the implementation in your derived class. The following code listing shows the Calculator class rewritten as an interface.

public interface ICalculator { double Add(double num1, double num2); } |

Instead of class or struct, you’ll use the interface type. A common convention for interface identifiers is the I prefix, as in ICalculator. Interface methods are implicitly public and virtual, so you don’t need access, abstract, or virtual modifiers. Like abstract methods, interface methods have a signature, but don’t have an implementation. Developers provide that implementation in their classes that derive from interfaces. The following code sample is a revision of the previous classes to implement the ICalculator interface.

public class ScientificCalculator : ICalculator { public double Add(double num1, double num2) { return num1 + num2; } } public class ProgrammerCalculator : ICalculator { public double Add(double num1, double num2) { return MyMathLib.Add(num1, num2); } } public class MyMathLib { public static double Add(double num1, double num2) { return num1 + num2; } } |

Deriving from an interface uses the same syntax as deriving from a class in that you add a colon and interface name after the class name. Unlike virtual methods, you don’t use an override modifier on methods.

A derived class implementation must be public. This make sense because an interface defines a contract that any derived class will have members defined in the interface. That means any time you use a class through its interface, you know that it will have the members defined by an interface. The following code example is a modification of the Main method that uses the ICalculator interface.

using System; public class Program { public static void Main() { ICalculator sciCalc = new ScientificCalculator(); double sciCalcResult = sciCalc.Add(2, 5); Console.WriteLine($"Scientific Calculator 2 + 5: {sciCalcResult}"); ICalculator prgCalc = new ProgrammerCalculator(); double prgCalcResult = prgCalc.Add(5, 10); Console.WriteLine($"Programmer Calculator 5 + 10: {prgCalcResult}"); Console.ReadKey(); } } |

The only syntax difference between this example and the one previous to that is the compile-time type of sciCalc and prgCalc is ICalculator. Because each variable is an ICalculator, you can be guaranteed that the runtime type implements the members of that interface.

Interfaces can also inherit other interfaces. In that case, derived classes must implement all members of each interface in the inheritance chain. Also, a class or struct can implement multiple interfaces, which is demonstrated in the following sample.

public interface ICalculator { } public interface IMath { } public class ScientificCalculator : ICalculator, IMath { public double Add(double num1, double num2) { return num1 + num2; } } |

After the first interface, additional interfaces appear in a comma-separated list. A class or struct must implement the methods of all interfaces it is derived from.

Object Lifetime

The lifetime of a value type (struct or enum) depends on where it’s allocated. Parameter and variable value type instances reside on the stack and exist for as long as they are in scope. Reference type instances (class) begin life when their constructors execute. The CLR allocates their space on the managed heap, and they exist until the CLR garbage collector (GC) cleans them up.

You can use constructors to initialize a class. While doing so, you can also affect initialization of static state, base types, and other constructor overloads. The following demo shows several features of class initialization.

using System; public class Calculator { static double pi = Math.PI; double startAngle = 0; public DateTime Created { get; } = DateTime.Now; static Calculator() { Console.WriteLine("static Calculator()"); } public Calculator() { Console.WriteLine("public Calculator()"); } public Calculator(int val) { Console.WriteLine("public Calculator(int)"); } } |

Calculator has a static constructor and two instance constructor overloads. A static constructor executes one time for the lifetime of the object and before the first constructor executes. The following sample is a derived class with similar members.

using System; public class ScientificCalculator : Calculator { static double pi = Math.PI; double startAngle = 0; static ScientificCalculator() { Console.WriteLine("static ScientificCalculator()"); } public ScientificCalculator() : this(0) { Console.WriteLine("public ScientificCalculator()"); } public ScientificCalculator(int val) { Console.WriteLine("public ScientificCalculator(int)"); } public ScientificCalculator(int val, string word) : base(val) { Console.WriteLine("public ScientificCalculator(int, string)"); } public double EndAngle { get; set; } } |

ScientificCalculator derives from Calculator and has similar constructors, except for the this and base operators. Using the this operator calls the constructor overload with the matching parameters. Since 0 is an int, the default (no parameter) constructor calls ScientificCalculator(int val) first. The base operator calls the matching constructor in the base class, so calling base(0) calls Calculator(int val) first. The following code listing is a program that instantiates these classes.

using System; class Program { static void Main() { var calc1 = new ScientificCalculator(); var calc2 = new ScientificCalculator(0, "x") { EndAngle = 360 }; Console.ReadKey(); } } |

And here is the program’s output:

static ScientificCalculator()

static Calculator()

public Calculator()

public ScientificCalculator(int)

public ScientificCalculator()

public Calculator(int)

public ScientificCalculator(int, string)

Viewing the output, you can see what executes first. Here are the rules that govern the instantiation of these classes:

- Static constructors execute before instance constructors.

- Static constructors execute one time for the life of the program.

- Base class constructors execute before derived class constructors.

- The this operator causes an overloaded constructor that matches the this parameter list to execute first.

- The base class default constructor executes, unless the derived class uses base to explicitly select a different base class constructor overload.

- This is not shown in the output of the previous example, but static fields initialize before the static constructor and instance fields initialize before instance constructors.

- Auto-implemented property initializers, such as Created, initialize at the same time as fields.

- Properties in object initialization syntax execute last as object initialization syntax is equivalent to populating the property through the instance variable after instantiation.

Note: In Visual Studio, you can set break points in the code and use the Immediate Window to inspect field values. You can experiment with different object initialization scenarios to get a feel for the initialization sequence.

Of all these lifecycle events, garbage collection (GC) is the least predictable. The CLR optimizes resources and runs GC when it needs to. This means that the lifetime of a reference type object is non-deterministic. There’s a rich body of theoretical discussion around the how and why of GC, but I’ll restrict that debate to the practical consideration of resource management. This includes closing files, database connections, operating system handles, and more.

To release resources, there’s a pattern commonly referred to as the Dispose Pattern. It relies on the IDisposable interface, flags that manage the disposal state of the object, and a destructor. The following code has constructor and Dispose method comments that imply a scenario where the class could be logging operations during its lifetime, and the log should be opened during instantiation and closed when the object is no longer needed.

using System; public class Calculator : IDisposable { static Calculator() { // Initialize log file stream. } #region IDisposable Support private bool disposedValue = false; // To detect redundant calls. protected virtual void Dispose(bool disposing) { if (!disposedValue) { if (disposing) { // TODO: dispose managed state (managed objects). // Close log file stream. } // TODO: free unmanaged resources (unmanaged objects) and override a finalizer below. // TODO: set large fields to null. disposedValue = true; } } // TODO: override a finalizer only if Dispose(bool disposing) above has code to free unmanaged resources. // ~Calculator() { // // Do not change this code. Put cleanup code in Dispose(bool disposing) above. // Dispose(false); // } // This code added to correctly implement the disposable pattern. public void Dispose() { // Do not change this code. Put cleanup code in Dispose(bool disposing) above. Dispose(true); // TODO: uncomment the following line if the finalizer is overridden above. // GC.SuppressFinalize(this); } #endregion } |

The code between #region and #endregion is automatically generated by VS. To generate this code, select IDisposable in the editor and the Quick Action icon (a light bulb) will appear. Open the Quick Action menu and select Implement interface with Dispose pattern. The #region and #endregion let VS fold the code so you won’t have to see it in the editor.

The Calculator class implements the IDisposable interface, which is only the Dispose method. The constructor initializes a resource you want to open, like a file handle or database, and the GC calls the destructor, ~Calculator(), if it’s uncommented. The Dispose() method calls Dispose(bool) with a true argument and ~Calculator() calls Dispose(bool) with a false argument. This lets Dispose(bool) know whether it should clean up managed resources that belong to the CLR or unmanaged resources that belong to the operating system. The flag disposedValue helps to prevent the object from being disposed more than one time.

The following sample shows how calling code can use this class, disposing it when it is no longer needed.

ScientificCalculator calc3 = null; try { calc3 = new ScientificCalculator(); // Do stuff. } finally { if (calc3 != null) calc3.Dispose(); } |

This shows the reason try-finally exists, to guarantee that resources can be closed or disposed. Because the finally block is guaranteed to execute after code in the try block starts, calc3 can be safely disposed. While that works, it’s more verbose than necessary. The following listing simplifies the code.

using (var calc4 = new ScientificCalculator()) { // Do stuff. } |

The using statement accepts parameters with any type that implements IDisposable. It takes care of calling Dispose() after the block completes execution. Behind the scenes, the logic is similar to the previous try-finally block.

Summary

C# supports object-oriented programming. For inheritance, you have single inheritance for classes, multiple inheritance for interfaces, and structs that can only inherit interfaces. Use abstract classes for classes that shouldn’t stand alone, but provide interface and structure to derived classes. Use interfaces when you don’t have implementation, need value type (struct) polymorphism, or need to implement multiple interfaces. I also discussed structs and how they are ideal for situations where copy by value leads to performance gains and value type semantics make sense. Unlike interfaces that you need to be public, use encapsulation to hide the internal workings that you don’t want other developers to use in their code. Polymorphism is a powerful concept that allows you to write a single algorithm that is coded the same for every instance, yet allows each instance to vary with an implementation specific to the runtime type of the instance. Pay attention to the sequence of object instantiation to ensure your types initialize correctly. If you need to dispose a type, make that type implement IDisposable with the Dispose Pattern. You can use a using statement to simplify the instantiation and safe cleanup of the type.

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.