CHAPTER 3

Hashing and Salting Passwords

Developers must understand the encryption area of software development. It is even more essential that developers know how to implement it correctly. Unfortunately, too often, sensitive data is not handled or stored correctly. The fact is that, at some point in your life, your personal information will most likely be compromised because the database it was stored on was hacked and dumped.

The issue (for developers, anyway) is not the fact that the database could be compromised. The real issue is how secure the data is that you write to the database.

Before we look at how to encrypt data, let’s quickly look at the mechanism we use to get the data into the database.

Note: Symmetric encryption is used on streams of large data while asymmetric encryption is performed on small amounts of data.

I recently had a difference of opinion with a member of a forum I contribute to. People there can pose questions (no, it’s not Stack Overflow), then members of the site can answer those questions and provide support.

In this case, the question related to writing data to a database. A forum member suggested a solution that was in line with what the author of the question had initially written. The problem was that the SQL was inline and not parametrized. This is bad practice. End of story. There is no debate. The member of the site who answered the question did not assist the author of the question in implementing a best practice. His argument was that he assisted the author of the question with the problem at hand, which was that the insert statement wasn’t working. While I can understand this, there is no excuse for assisting the author of the question without telling him that his implementation is bad practice. And, more worrying was the fact that the question’s author accepted the solution, which was an implementation of the insert statement that we all know is bad practice.

You as a developer have a responsibility to keep the data as secure as possible for as long as possible, up until it is written to the database. In other words, do not do what we see in Code Listing 14.

Code Listing 14: Bad SQL Insert Logic

Not only is this bad practice, but it will come back to bite you at some point in your career. Just ask the developers at a small development company who wrote an access control application for a client. When the client decided to have the code audited by an outside firm, the code failed miserably. The repercussions were disastrous for the development company involved.

Instead of the inline SQL, consider this coding approach below as better in terms of securing your code.

Code Listing 15: Good SQL Insert Logic

private void SaveUserData(string name, string surname, string username, string password, string email) { SqlCommand cmd = new SqlCommand(); cmd.CommandType = CommandType.StoredProcedure; cmd.CommandText = "sproc_InsertUserData"; cmd.Parameters.Add("Name", SqlDbType.NVarChar, 50).Value = name; cmd.Parameters.Add("Surname", SqlDbType.NVarChar, 50).Value = surname; cmd.Parameters.Add("Username", SqlDbType.NVarChar, 50).Value = username; cmd.Parameters.Add("Password", SqlDbType.NVarChar, 50).Value = password; cmd.Parameters.Add("Email", SqlDbType.NVarChar, 50).Value = email; ExecuteNonQuery(cmd); } |

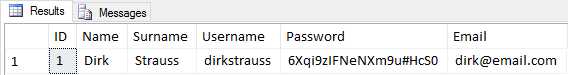

Now that we have that out of the way, let’s have a look at encrypting the data you write to the database. If the data you store in the database looks like Figure 6, you still have a problem.

Figure 6: User Table Data

The data is visible to anyone who cares to take a look. SQL administrators can see the information at will. Worst case scenario, if the database is ever hacked, your data is a free-for-all for anyone out there.

The problem is compounded by the use of:

- Weak passwords—developers need to ensure strong passwords in their systems.

- Single passwords across all sites—over this, you have no control.

Even though the password in the table above is quite strong, it is still visible to anyone who cares to look. Apart from using strong passwords, we need to encrypt the rest of the data. Let’s have a look at how to accomplish this.

Encrypting user details

We want to take the users’ personal data and store it in the database using a method called salting and hashing. We salt the data to be encrypted and, in doing so, make it more complex and more random. A common way to crack encrypted data is by using lookup tables or rainbow tables. By using a salt, we ensure that we add a truly random value to the password so that even if two users in the system have the same password, a truly random hash (encrypted value) is generated.

Note: Salt is random data that is added to the password before it is hashed.

In the town where I grew up, there was another Dirk Strauss. This bloke must have been a golf player, because I had people coming up to me (people I’d known for years) congratulating me for winning some golf tournament or other. I never met the guy, but consider the possibility of two users with the same password. If they use weak passwords, that possibility is all the more probable.

Table 1

User | Weak Password |

Dirk Strauss (the real one) | d1Rk$tr@u55 |

Dirk Strauss (the golfer) | d1Rk$tr@u55 |

If both of us use the very weak password of d1Rk$tr@u55, then it would not stand up very well against any type of attack. The possibility of coming across such a similar weak password is very likely, especially in a large organization or on a public website. In fact, I have recently seen passwords in a database (spot the error here? No encryption) entered as ian and mark123 and, shockingly, simply 1.

Tip: If you use this type of password, stop using it. Use an application such as LastPass to generate truly unique passwords while also managing those passwords for you across the Internet.

The encrypted password generated for me if salting is used during encryption:

- User: Dirk

- Salt: fxJis2foDGEnmx6XTGNQNi3ECvxEDSYEsv/71ds17a0=

- Encrypt: fxJis2foDGEnmx6XTGNQNi3ECvxEDSYEsv/71ds17a0=+d1Rk$tr@u55

- Hashed Value: c/LUZdrhzkD8iOr6BLZORbawtYubcyggbsjleQceJ+4=

The encrypted password generated for the golfer if salting is used during encryption:

- User: Golfer

- Salt: icqlqXBkYQgerEfzQx/lm3/XdpsIHswR5CNiKeC35qs=

- Encrypt: icqlqXBkYQgerEfzQx/lm3/XdpsIHswR5CNiKeC35qs=+d1Rk$tr@u55

- Hashed Value: FBxS85sYOPQX3hIcijiM8NHcnWWOibJamJeDrtCIuYk=

As you can see, even though two different users use the same weak password, the encrypted passwords generated are totally different.

Tip: Always enforce strong passwords in your applications. Salting and hashing do not prevent passwords from being guessed.

Now that we have established that salting is essential, we must decide if we are going to concatenate the salt to the beginning or the end of the password. It does not matter if you add the salt at the beginning or the end, just ensure that whatever you decide (beginning or end), you do it consistently each time.

A few rules when working with salt:

- Never reuse the salt in each hash.

- Never hard code a value in the code to use as the salt.

- Don’t use a short salt.

- Never use the username or any other entered data as the salt—it must be random.

- If the user ever changes their password (or any other secure info), generate a new salt.

A good practice is to generate a new salt for each value that you encrypt. You then store the salt with the encrypted data in each field of the database table. This means that you have a different random salt for every value, which makes the information you encrypt very secure.

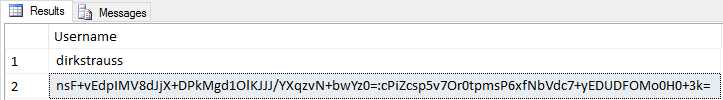

In the examples below, the encrypted data is stored with a colon “:” separating the salt and encrypted value as [encrypted value]:[salt value]. You can see the old value for the username, as opposed to the newly encrypted and salted value for the username.

Figure 7: Salted and Encrypted Username

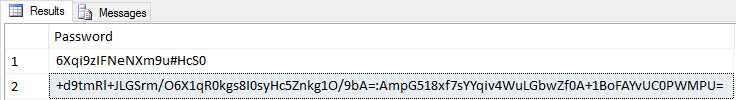

If we look at the password field, you will notice that the salt used to encrypt the password is not the same salt used to encrypt the username. Compared to the old value stored for the password, the new encrypted and salted password is more secure.

Figure 8: Salted and Encrypted Password

We therefore ensure that the data we encrypt is very secure. So how do we do this? Consider the example in Code Listing 16:

Code Listing 16: Encrypting Data

private static string EncryptData(string valueToEncrypt) { string GenerateSalt() { RNGCryptoServiceProvider crypto = new RNGCryptoServiceProvider(); byte[] salt = new byte[32]; crypto.GetBytes(salt); return Convert.ToBase64String(salt); } string EncryptValue(string strvalue) { string saltValue = GenerateSalt(); byte[] saltedPassword = Encoding.UTF8.GetBytes(saltValue + strvalue); SHA256Managed hashstr = new SHA256Managed(); byte[] hash = hashstr.ComputeHash(saltedPassword); return $"{Convert.ToBase64String(hash)}:{saltValue}"; }

return EncryptValue(valueToEncrypt); } |

The method EncryptData() receives a value to encrypt (valueToEncrypt) and returns the encrypted value in the return statement.

Inside the EncryptData() method, there are two local functions called GenerateSalt() and EncryptValue(). The GenerateSalt() local function ensures that a unique salt value is created for every value you pass to the EncryptValue() local function. The encrypted value and its salt are returned to the calling code.

Note: Local functions is a new feature of C# 7.

To test the encryption code, simply create some hard coded values and pass them to the EncryptData() method. The string returned to the calling code will be the salted and encrypted value that you can store inside the database.

Code Listing 17: Testing Encryption

|

string surname = "Strauss"; string username = "dirkstrauss"; string password = "6Xqi9zIFNeNXm9u#HcS0"; string email = "[email protected]"; string encryptedName = EncryptData(name); string encryptedSurname = EncryptData(surname); string encryptedUsername = EncryptData(username); string encryptedPassword = EncryptData(password); string encryptedEmail = EncryptData(email); |

Output these values to the console window and see the results, as in Figure 9.

Figure 9: Encrypted Results

Even if the database is compromised at some point, the data stored inside the database is still quite secure. Putting the code together using a stored procedure and parameters, we get the example in Code Listing 18.

Code Listing 18: Writing to the Database

You will notice that I have used nvarchar(max) in the database fields, therefore the -1 is used as the size of the field.

Code Listing 19: Parameter

cmd.Parameters.Add("Password", SqlDbType.NVarChar, -1).Value = EncryptData(password); |

Validating user details

Now that we have ensured that the data stored in the database is secure, what do we do when we need to validate that the username or password typed in by the user is correct? A rule of thumb is that you should never encrypt the data stored in the database. Instead, you encrypt the data entered at a login page and compare that to the encrypted data stored in the database. For example, if the two values match each other, the user has entered the correct password.

In the EncryptData() method, we returned the encrypted data as $"{Convert.ToBase64String(hash)}:{saltValue}"; where the hash is the encrypted data and the saltValue is the salt we used during encryption. We separate the encrypted data and the salt by using a : character. We need to keep this in mind when we validate the user input. Consider the ValidateEncryptedData() method.

Code Listing 20: Validate User Input

private static bool ValidateEncryptedData(string valueToValidate, string valueFromDatabase) { string[] arrValues = valueFromDatabase.Split(':'); string encryptedDbValue = arrValues[0]; string salt = arrValues[1]; byte[] saltedValue = Encoding.UTF8.GetBytes(salt + valueToValidate); SHA256Managed hashstr = new SHA256Managed(); byte[] hash = hashstr.ComputeHash(saltedValue); string enteredValueToValidate = Convert.ToBase64String(hash); return encryptedDbValue.Equals(enteredValueToValidate); } |

The encrypted string is split using the : character. Because we stored the values as [encrypted value]:[salt value] it means that arrValues[0] will contain the encrypted value and arrValues[1] will contain the salt.

Also remember that when we encrypted the data, we prefixed the value to encrypt with the salt value as follows: saltValue + valueToEncrypt. This means that we need to be consistent when validating the entered data.

Inside the ValidateEncryptedData() method, we then must salt the value to validate in the same way.

Code Listing 21: Order of Salt and Value

We follow the same essential process as when we were encrypting the data. The value the user entered is salted with the same salt that the original value was salted with and then encrypted. We then do a string comparison of the encrypted value read from the database and the encrypted value the user entered.

If two encrypted values match, the data was entered correctly and you can validate the user. Testing the code can be done as in Code Listing 22.

Code Listing 22: Validating User Password

string name = "Dirk"; string surname = "Strauss"; string username = "dirkstrauss"; string password = "6Xqi9zIFNeNXm9u#HcS0"; string email = "[email protected]"; string encryptedName = EncryptData(name); string encryptedSurname = EncryptData(surname); string encryptedUsername = EncryptData(username); string encryptedPassword = EncryptData(password); string encryptedEmail = EncryptData(email);

if (ValidateEncryptedData(password, encryptedPassword)) WriteLine($"The {nameof(password)} entered is correct"); else WriteLine($"The {nameof(password)} entered is not correct"); |

Place a breakpoint just before the entered password must be validated. Hover over the password variable and pin it.

Figure 10: Testing Validation

Change the password variable value that you pinned to anything else.

Figure 11: Changing Password to Validate

Continue the debugging and you will see that the encrypted value of the password variable we changed did not match the encrypted value of the encryptedPassword variable. Validation therefore fails.

Figure 12: Password Not Validated

Encrypting user data using a salt and hash is essential if you are storing user login details.

How strong are unsalted passwords?

Just have a look at crackstation.net. You can test up to 20 nonsalted hashes using their free password hash cracker.

The crackstation.net folks created the lookup tables by scraping every word in the Wikipedia databases and adding as many password lists as they could find. The lookup tables then store a mapping between the hash of a password and the actual password.

The result? At the time of this writing, they had a 190 GB, 15 billion entry lookup table for MD5 and SHA1 hashes. For other hashes, they have a 19 GB, 1.5 billion entry lookup table.

Salt your data before encryption.

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.