CHAPTER 3

Data Modeling with Cassandra and CQL

If you are coming from the relational world, it will take some time for you to get used to the many ways problems are solved in Cassandra. The hardest thing to let go of is data normalization. In the relational world, data is split into multiple tables so that the data has very little redundancy. The data is logically grouped and stored, and if we need a certain view on this data, we make a query and present the desired data to the user.

With Cassandra the story is a bit different. We have to think about how our data is going to be queried from the start. This causes a lot of write commands to the database because data is often inserted into multiple tables every time we store something in Cassandra. One of the first thoughts that may come to mind here is that this is not going to be responsive or fast, but remember, Cassandra is really fast at writing.

Another concern you may have is that this will probably store a lot more data than we actually need, and you are right about that; Cassandra will probably store a lot more data on the disk than a relational database will. This heavy writing pays off when running queries because the queries are already prepared and there is no complex, time-consuming data joining. The entire Cassandra philosophy could be summarized with the premise that the disk is cheap.

Comparing Relational and Cassandra Data Storage

To compare classical relational storage and Cassandra, we need to start with the model. As an example, we’ll use an online used car market. Let’s start with the relational data model.

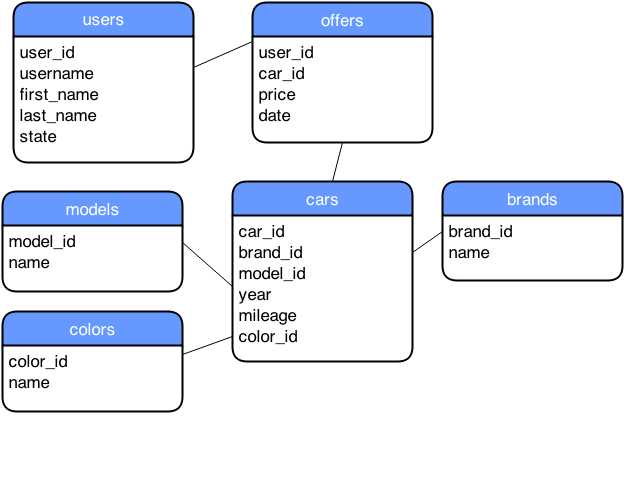

- Simple relational model of an online car market

Figure 35 shows a simple relational model for an online used car market. Every box in the figure would become a separate table in a relational database. Elements inside the boxes would become columns in the tables. Every stored row would have each column defined in the model saved to the disk. If the creator of the table specifies it, the columns can have an undefined or a null value, but they would still be stored on the disk. When relational data from the model in Figure 35 is stored, it might look something like the following figure.

- Example of stored relational data

To examine Cassandra’s way of storing data, we first have to look at how the data is actually structured.

- Cassandra Data Structuring

We already talked about the keyspace and the column family. Column family is also often simply called a table. A row in Cassandra can have all of the columns defined or just some of them. Cassandra will save only actual values to the row. Cassandra’s limitation for a row is that it must fit on a single node. The second limitation for a row is that it can have at most two billion columns. In most cases, this is more than enough, and if you exceed that number, the data model you defined probably needs some tweaking.

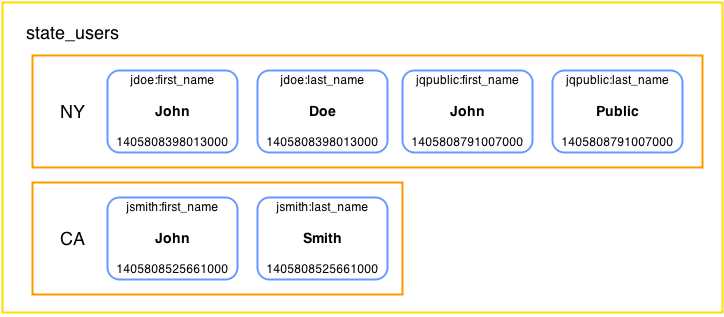

The previous figure shows columns in a row storing a value and a time stamp. The columns are always sorted within a row by the column name. We’ll discuss how to model the example of the used car market with Cassandra in the next sections, but for now, let’s just show how the user’s table would be stored in Cassandra. Note that we didn’t use an auto-increment key as is often the case with relational data modeling; rather, we used a natural key username. For now, let’s skip the CQL stuff and just look at the stored data at an abstract level:

- Cassandra storing example user data

The previous figure shows the low-level, data-storing technique Cassandra uses. The example is pretty similar to the way the relational database stores data. Now, let’s look at the way the data is stored if the row keys were the states and the clustering columns were the usernames. Also, let’s add John Q. Public to NY to illustrate the difference.

- Cassandra storing example user data with state as partition key

The data storage in the previous figure might seem a little strange at the moment because column names are fairly fixed in relational database storage systems. It uses a username to group the columns belonging to a single user into a group. Remember, columns are always sorted by their names. Also note that there is no column for the username and that it’s stored only in the column name. However, this approach to storage does not allow direct fetching of users by their username. To access any of the data contained within the row (partition), we need to provide a state name.

Now that we know how Cassandra is handling the data internally, let’s try it in practice. By now, we have talked about a lot of Cassandra concepts and how they differ from relational databases. In the next section, we’ll dive into the CQL, the language used for interacting with Cassandra.

CQL

CQL, or Cassandra Query Language, is not the only way of interacting with Cassandra. Not long ago, Thrift API was the main way of interacting with it. The usage, organization, and syntax of this API were oriented toward exposing the internal mechanisms of Cassandra storage directly to the user.

CQL is the officially recommended way to interact with Cassandra. The current version of CQL is CQL3. CQL3 was a major update from CQL2. It added CREATE TABLE syntax to allow multicolumn primary keys, comparison operators in WHERE clauses on columns besides the partition key, ORDER BY syntax, and more. The main difference from standard SQL is that CQL does not support joins or subqueries. One of the main goals of CQL is, in fact, giving users the familiar feeling of working with SQL.

CQL Shell

In the previous chapter we looked at how to install and run DataStax DevCenter. If you don’t want to use the DataStax DevCenter, go to the directory where you installed Cassandra, and then go to the bin directory and run the cqlsh utility.

# ./cqlsh Connected to Test Cluster at localhost:9160. [cqlsh 4.1.1 | Cassandra 2.0.9 | CQL spec 3.1.1 | Thrift protocol 19.39.0] Use HELP for help. cqlsh> |

Code Listing 3

After running the CQL shell, you can start issuing instructions to Cassandra. The CQL shell is fine for most of the day-to-day work with Cassandra. In fact, it is the admin’s preferred tool because of its command-line nature and availability. Remember, it comes bundled with Cassandra. DevCenter is more for developing complex scripts and developer efficiency.

Keyspace

Before doing any work with the tables in Cassandra, we have to create a container for them, otherwise known as a keyspace. One of the main uses for keyspaces is defining a replication mechanism for a group of tables. We’ll start by defining a keyspace for our used car market example.

CREATE KEYSPACE used_cars WITH replication = { 'class': 'SimpleStrategy', 'replication_factor' : 1}; |

Code Listing 4

When creating a keyspace, we have to specify the replication. Two components defining the replication are class and replication_factor. In our example, we have used SimpleStrategy for the class option; it replicates the data to the next node on the ring without any network-aware mechanisms.

At the moment, we are in the development environment with only one node in the cluster so a replication factor of one is sufficient. In fact, if we specified a higher replication factor—3, for instance—and then used the quorum option when performing selects, the select commands would fail because quorum cannot be reached with a replication factor 3 because 2 nodes have to respond, and we have only one node in our cluster at the moment. If we added more nodes to the cluster and would like the data to be replicated, we can update the replication factor with the ALTER KEYSPACE command as shown in the following code example.

ALTER KEYSPACE used_cars WITH REPLICATION = { 'class' : 'SimpleStrategy', 'replication_factor' : 3}; |

Code Listing 5

SimpleStrategy will not be enough in some cases. The first chapter mentioned that Cassandra uses a component called snitch to determine the network topology and then uses different replication mechanisms that are network-aware. To enable this behavior on the keyspace, we have to use the NetworkTopologyStrategy replication class, as shown in the following example.

CREATE KEYSPACE used_cars WITH replication = { 'class': 'NetworkTopologyStrategy', 'DC1' : 1, 'DC2' : 3}; |

Code Listing 6

The previous example replicates the used_cars keyspace with replication factor 1 in DC1 and replication factor 3 in DC2. Data center names DC1 and DC2 are defined in node configuration files. We don’t have any data centers specified in our current environment but the command will still run and create a keyspace with the options that we specified.

On some occasions, we will need to delete the complete keyspace. This is achieved with the DROP KEYSPACE command. The command is pretty simple and has only one parameter: the name of the keyspace that we want to delete. Keyspace removal is irreversible and issuing the command causes immediate removal of the keyspace and all of its column families and their data.

DROP KEYSPACE used_cars; |

Code Listing 7

The DROP KEYSPACE command is primarily used in development scenarios, migration scenarios, or both. If you drop a keyspace, the data is removed from the system and can only be restored from a backup.

When issuing commands in the CQL shell, we usually have to provide a keyspace and table. The following SELECT command lists all users in the used_cars keyspace.

SELECT * FROM used_cars.users; username | first_name | last_name | state ----------+------------+-----------+------- jdoe | John | Doe | NY jsmith | John | Smith | CA |

Code Listing 8

This becomes a bit tedious over time, and most of the operations issued in sequence are usually within a single keyspace. So, to reduce the writing overhead, we can issue the USE command.

USE used_cars; |

Code Listing 9

After running the USE command, all of the subsequent queries are run within the specified keyspace. This makes writing queries a bit easier.

Table

Defining and creating tables is the foundation for building any application. Although the syntax of CQL is similar to SQL, there are important differences when creating tables. Let’s start with the most basic table for storing users.

CREATE TABLE users ( username text, password text, first_name text, last_name text, state text, PRIMARY KEY (username) ); |

Code Listing 10

PRIMARY KEY is required when defining a table. It can have one or more component columns, but it cannot be a counter column. If the PRIMARY KEY consists of only one column, you can place PRIMARY KEY into the column definition after specifying the column type.

CREATE TABLE users ( username text PRIMARY KEY, password text, first_name text, last_name text, state text ); |

Code Listing 11

If we were using SQL and a relational database to specify columns in the PRIMARY KEY, all of the columns would be treated the same. In the previous chapter we discussed how Cassandra stores data, and that all data is saved in wide rows. Each row is identified by an ID. In Cassandra terminology, this ID is called the partition key. The partition key is the first column from the list of columns in the PRIMARY KEY definition.

Note: The first column in the PRIMARY KEY list is the partition (row) key.

Let’s use an example to see what is going on with the columns specified after the first place in the PRIMARY KEY list. We will model the offers shown when we compared relational and Cassandra data storage. We mentioned earlier that normalization is not common when working with Cassandra. The relational example we used stored the data about car offerings into five tables. Here, we are going to use just one table, at least for now.

CREATE TABLE offers ( username text, date timestamp, price float, brand text, model text, year int, mileage int, color text, PRIMARY KEY (username, date) ); |

Code Listing 12

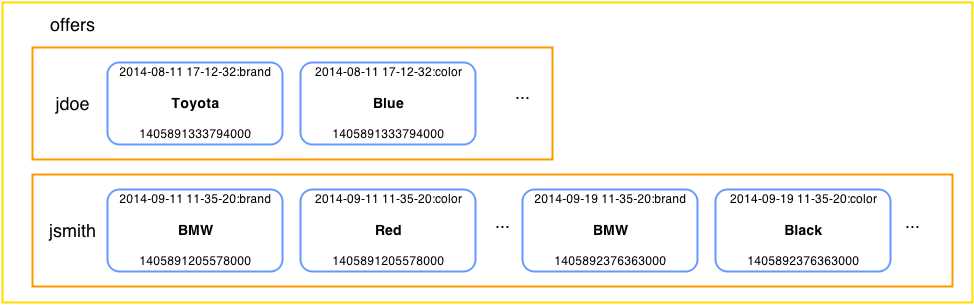

The PRIMARY KEY definition consists of two columns. The first column in the list is the partition key. All of the subsequent listed columns after the partition key are clustering keys. The clustering keys influence how Cassandra is organizing the data on the storage level. To keep things simple, we’ll just concentrate on brand and color to show what the clustering key does. The table with offers might look something like the following when queried.

username | date | brand | color ----------+--------------------------+--------+------- jdoe | 2014-08-11 17:12:32+0200 | Toyota | Blue jsmith | 2014-09-09 11:35:20+0200 | BMW | Red jsmith | 2014-09-19 11:35:20+0200 | BMW | Black |

Code Listing 13

This looks pretty similar to what we would expect from a table in relational storage.

When it comes down to physically storing the data, the situation is a bit different. The clustering key date is combined with the names of the other columns. This causes the offers to be sorted by date within the row.

- Cassandra storing offers data with date as clustering key

Now the question is, what would happen if we didn’t add date to the second place in the PRIMARY KEY list, causing it to become a clustering key? If you look more carefully, the column names in the previous figure are combinations of date and column names such as brand and color. If we removed date as a clustering key, every user would have just one used car offer and that’s it. date would become just another column and we would lose the possibility to add more offers per user.

Sometimes data will be too large for a single row. In that case, we combine the row ID with other data to split the data further into smaller chunks. For instance, if our site became mega popular and if all car retailers offered their cars on our site, we would somehow have to split the data. Perhaps the most reasonable way to do it would be to split the data by the car brand.

CREATE TABLE offers_by_brand ( username text, date timestamp, price float, brand text, model text, year int, mileage int, color text, PRIMARY KEY ((username, brand), date) ); |

Code Listing 14

Note that if a row is a combination of username and brand, we will be unable to access the offers without specifying the username and brand when fetching the row. Sometimes when such a technique is used, the application has to combine the data to present it to the user. A partition (row) key that consists of more than one column is called a composite partition key. A composite partition key is defined by listing the columns in parentheses. Remember, only the first column in the list is the partition key. If we want more columns to go into the partition key, we have to put them in parentheses.

CQL Data Types

At this point we have used different types to specify column data but have yet to discuss them. The following table provides a short overview of the data types in Cassandra.

- CQL Data Types

Type | Description |

|---|---|

ascii | US-ASCII character string |

bigint | 64-bit signed long |

blob | Arbitrary bytes (no validation), expressed as hexadecimal in CQL shell. DevCenter only shows <<blob>>. |

boolean | true or false |

counter | 64-bit distributed counter value |

decimal | Variable-precision decimal |

double | 64-bit IEEE-754 floating point |

float | 32-bit IEEE-754 floating point |

inet | IP address string (supports both IPV4 and IPV6 formats) |

int | 32-bit signed integer |

list | A collection of ordered elements |

map | Associative array |

set | Unordered collection of elements |

text | UTF-8 encoded string |

timestamp | Date and time, encoded as 8-byte integers starting from 1.1.1970 |

uuid | UUID in standard format |

timeuuid | UUID with a time stamp in its value |

varchar | UTF-8 encoded string |

varint | Arbitary-precision integer |

The column type is defined by specifying it after the column name. Changing column type is possible if the types are compatible. If the types are not compatible, the query will return an error. Also note that the application might stop functioning because the types may not be compatible on the application level. Changing the clustering column or columns that have indexes defined on them is not possible. For instance, changing the year column type from int to text is not allowed and causes the following error.

ALTER TABLE offers_by_hand ALTER year TYPE text; |

Code Listing 15

Adding columns to Cassandra tables is a common and standard operation.

ALTER TABLE offers ADD airbags int; |

Code Listing 16

The previous code listing adds an integer type column called airbags to the table. In our example this column stores the number of airbags the vehicle has. Dropping the column is done with the DROP subcommand from the ALTER TABLE command.

ALTER TABLE offers DROP airbags; |

Code Listing 17

To complete the life cycle of a table, we have to run two more commands. The first is for emptying all of the data from the table.

TRUNCATE offers; |

Code Listing 18

The final command is for dropping the entire table.

DROP TABLE offers; |

Code Listing 19

Table Properties

Besides column names and types, CQL can also be used to set up the properties of a table. Some properties such as comments are used for easier maintenance and development, and some go really deep into the inner workings of Cassandra.

- CQL Table Properties

Property | Description |

|---|---|

bloom_filter_fp_chance | False-positive probability for SSTable Bloom filter. This value ranges from 0, which produces the biggest possible Bloom filter, to 1.0, which disables the Bloom filter. The recommended value is 0.1. Default values depend on the compaction strategy. SizeTieredCompaction has a default vaule of 0.01 and LeveledCompaction has a default value of 0.1. |

caching | Cache memory optimization. The available levels are all, keys_only, rows_only, and none. The rows_only option should be used with caution because Cassandra puts a lot of data into memory when that option is enabled. |

comment | Used primarily by admins and developers to make remarks and notes about the tables. |

compaction | Sets the compaction strategy for the table. There are two: the default SizeTieredCompactionStrategy and LeveledCompactionStrategy. SizeTiered triggers compaction when the SSTable passes a certain limit. The positive aspect of this strategy is that it doesn’t degrade write performance. The negative is that it occasionally uses double the data size on the disk and has potentially poor read performance. LeveledCompaction has multiple levels of SSTables. At the lowest level there are 5 MB tables. Over time, the tables are merged into a table that is 10 times bigger; this causes very good read performance. |

compression | Determines how the data is going to be compressed. Users can choose speed or space savings. The greater the speed, the less disk space is saved. In order from fastest to slowest, the compressions are LZ4Compressor, SnappyCompressor, DeflateCompressor. |

dclocal_read_repair_chance | Probability of invoking read repairs. |

gc_grace_seconds | Time to wait for removal of data with tombstones. The default is 10 days. |

populate_io_cache_on_flush | This value is disabled by default; enable this only if you expect all the data to fit into memory. |

read_repair_chance | Number between 0 and 1.0 specifying the probability to repair data when quorum is not reached. Default value is 0.1 |

replicate_on_write | This applies only to counter tables. When set, replicas write to all affected replicas, ignoring the specified consistency level. |

Defining tables with comments is pretty easy and represents a positive practice for maintenance and administration of the database.

CREATE TABLE test_comments ( a text, b text, c text, PRIMARY KEY (a) ) WITH comment = 'This is a very useful comment'; |

Code Listing 20

Most of the options are simple to define. Adding a comment is a nice example of such an option. On the other hand, compression and compaction options have subproperties. Defining the subproperties is done with the help of a JSON-like syntax. We’ll look at an example shortly.

- CQL Table Compression Options

Property | Description |

|---|---|

sstable_compression | Specifies the compression algorithm to use. The available algorithms were listed in the previous table: LY4Compressor, SnappyCompressor, and DeflateCompressor. To disable compression, simply use an empty string. |

chunk_length_kb | SSTables are compressed by block. Larger values generally provide better compression rates but increase the data size for reading. By default, this option is set to 64KB. |

crc_check_chance | All compressed data in Cassandra has a checksum block. This value is used to check that the data is not corrupt so that it isn’t sent to other replicas. By default, this option is set to 1.0 so that every time the data is read, the node checks the checksum value. Setting this value to 0 disables the checksum checking and setting it to 0.33 causes checksum to be checked every third time the data is read. |

Manipulating compression options can lead to significant performance gains, and many Cassandra solutions out there run with compression options set to non-default values. Indeed, tuned compression options are sometimes very important for a successful Cassandra deployment, but most of the time, especially if you are just starting to use Apache Cassandra, you will be just fine using the default SnappyCompressor settings as the compression option.

Compaction has many subproperties as well.

- CQL Table Compaction Options

Property | Description |

|---|---|

enabled | Determines whether compaction will run on the table. By default, all tables have compaction enabled. |

tombstone_threshold | Ratio value from 0 to 1 specifying how many columns have to be marked with tombstones to begin compaction. The default value is 0.2. |

tombstone_compaction_interval | Minimum time to wait after SSTable creation to start compaction, but only after the tombstone_threshold has been reached. The default setting is one day. |

unchecked_tombstone_compaction | Enables aggressive compaction, which runs compaction on the checked interval even if the SSTable hasn’t reached the threshold. By default, this is set to false. |

min_sstable_size | Used with SizeTieredCompactionStrategy. This option is used to prevent grouping SSTables into too-small chunks. It is set to 50MB by default. |

min_threshold | Available in SizeTieredCompactionStrategy. Represents a minimum number of SSTables needed to start a minor compaction process. It is set to 4 by default. |

max_threshold | Only available in SizeTieredCompactionStrategy. Sets the maximum number of tables processed by minor compaction. It is set to 32 by default. |

bucket_low | For SizeTieredCompactionStrategy only. Checks for tables with a difference in size below the group average. The default value is 0.5, meaning only tables whose sizes diverge by a maximum of 50 percent. |

bucket_high | For SizeTieredCompactionStrategy only. Checks for compaction on tables whose sizes are larger than the group average. The default setting is 1.5, meaning all tables 50 percent larger than the group average. |

sstable_size_in_mb | Available only in the LeveledCompactionStrategy. Represents the targeted SSTable size, but the size may be slightly larger or smaller because row data is never split between two SSTables. It is set to 5MB by default. |

The options for compression and compaction options are defined with JSON-like syntax.

CREATE TABLE inventory ( id uuid, name text, color text, count varint, PRIMARY KEY (id) ) WITH compression = { 'sstable_compression' : 'DeflateCompressor', 'chunk_length_kb' : 64 } AND compaction = { 'class' : 'SizeTieredCompactionStrategy', 'min_threshold' : 6 }; |

Code Listing 21

Cluster Ordering the Data

Previously we noted that columns within a row on the disk are sorted. When fetching the data from physical rows in the table, we get the data presorted by the specified clustering keys. If the data is, by default, in ascending order, then fetching in descending order causes performance issues over time. To prevent this from happening, we can instruct Cassandra to keep the data in a row of a table in descending order with CLUSTERING ORDER BY.

CREATE TABLE latest_offers ( username text, date timestamp, price float, brand text, model text, year int, mileage int, color text, PRIMARY KEY (username, date) ) WITH CLUSTERING ORDER BY (date DESC); |

Code Listing 22

It is important to remember that the previous CREATE TABLE example keeps the data sorted in descending order but only within the row. This means that selecting the data from a specific user row with a username will show sorted data for that user, but if you select all the data from the table without providing the row key (username), the data will not be sorted by username.

Tip: Clustering sorts the data within the partition, not the partitions.

But just to remember all this even better, let’s consider an example. Let’s go back to our offers table. The offers table is sorted in ascending order by default, but this is fine for demonstrating what the previous tip is all about. First, we’ll select the offers for the jsmith user.

SELECT username, date, brand, color FROM offers WHERE username = 'jsmith'; username | date | brand | color ----------+--------------------------+-------+------- jsmith | 2014-09-09 11:35:20+0200 | BMW | Red jsmith | 2014-09-19 11:35:20+0200 | BMW | Black jsmith | 2014-09-20 17:12:32+0200 | Audi | White |

Code Listing 23

Notice that these offers are sorted in ascending order, with the oldest record being in the first place. And that’s what we would expect if the data were sorted by date since this column is the clustering key. But some Cassandra users may be confused when they try to access the whole table without providing the row key (username):

SELECT username, date, brand, color FROM offers; username | date | brand | color ----------+--------------------------+--------+-------- jdoe | 2014-08-11 17:12:32+0200 | Toyota | Blue jdoe | 2014-08-25 11:13:22+0200 | Audi | Orange jsmith | 2014-09-09 11:35:20+0200 | BMW | Red jsmith | 2014-09-19 11:35:20+0200 | BMW | Black jsmith | 2014-09-20 17:12:32+0200 | Audi | White adoe | 2014-08-26 10:11:10+0200 | VW | Black |

Code Listing 24

Notice that the data has no sorting whatsoever by the username (row ID, partition key) column. Once again, the data is sorted within a username but not between usernames.

Manipulating the Data

Up until now, we have been concentrating mostly on the data structure and the various options and techniques for organizing stored data. We covered the basic data reading but we’ll look at more advanced examples of data retrieval soon. Inserting data looks pretty much like it does in standard SQL databases; we define the table name and the columns and then specify the values. One of the simplest examples is entering data into the users table.

INSERT INTO users (username, password, first_name, last_name, state) VALUES ('jqpublic', 'hello1', 'John', 'Public', 'NY'); |

Code Listing 25

The previous code shows you how to insert data into the users table. It has only text columns so all of the inserted values are strings. A more complex example would be to insert values into the offers table, as in the following example.

INSERT INTO offers (username, date, price, brand, model, year, mileage, color) VALUES ('jsmith', '2014-09-19 11:35:20', 6000, 'BMW', '120i', 2010, 40000, 'Black'); |

Code Listing 26

Working with strings and numbers is pretty straightforward. Numbers are more or less simple; the decimal separator is always a period because insert parameters are split with a comma. A number cannot begin with a plus sign, only a minus sign. The numbers can also be entered with scientific notation, so both “e” and “E” are valid when specifying a floating-point number. Note that DataStax DevCenter marks numbers defined with an “e” as incorrect syntax usage, while the CQL shell interprets both signs as valid. After the “e” that specifies the exponent, a plus or minus sign can follow. The following code example inserts a car that costs $8,000 specified in scientific notation with a negative exponent prefix.

INSERT INTO offers (username, date, price, brand, model, year, mileage, color) VALUES ('jsmith', '2014-05-11 01:22:11', 80000.0E-1, 'FORD', 'Orion', 206, 200000, 'White'); |

Code Listing 27

Strings are always placed inside single quotation marks. If you need the single quotation mark in the data, escape it with another single quotation mark before placing it in the string as in the following example.

INSERT INTO test_data(stringval) VALUES ('O''Hara'); |

Code Listing 28

Besides numbers and strings, the previous queries also contain dates. Dates are defined as the timestamp type in Cassandra. A timestamp can simply be entered as an integer, representing the number of milliseconds that have passed since January 1, 1970 at 00:00:00 GMT. The string literals for entering timestamp data in Cassandra are entered in the following formats.

- Timestamp String Literal Formats

Format | Example |

yyyy-mm-dd HH:mm | '2014-07-24 23:23' |

yyyy-mm-dd HH:mm:ss | '2014-07-24 23:23:40' |

yyyy-mm-dd HH:mmZ | '2014-07-24 23:23+0200' |

yyyy-mm-dd HH:mm:ssZ | '2014-07-24 23:23:40+0200' |

yyyy-mm-dd'T'HH:mm | '2014-07-24T23:23' |

yyyy-mm-dd'T'HH:mmZ | '2014-07-24T23:23+0200' |

yyyy-mm-dd'T'HH:mm:ss | '2014-07-24T23:23:40' |

yyyy-mm-dd'T'HH:mm:ssZ | '2014-07-24T23:23:40+0200' |

yyyy-mm-dd | '2014-07-24' |

yyyy-mm-ddZ | '2014-07-24+0200' |

The format is pretty standard in many programming languages and database environments. Besides using a space to separate the date and time parts, sometimes they are separated with a T. The time zone is specified in a four-digit format and is noted with the letter Z in the format examples in the previous table. The time zone can begin with a plus or a minus sign, depending on the position of the time zone compared to GMT (Greenwich Mean Time). The first two digits represent the difference in hours and the last two digits represent the difference in minutes.

Most time zones are an integer difference when compared to GMT. Some regions have an additional half hour offset, such as Sri Lanka, Afghanistan, Iran, Myanmar, Newfoundland, Venezuela, Nepal, the Chatham Islands, and some regions of Australia. If no time zone is specified, the time zone from the coordinator node is used. Most of the documentation recommends specifying the time zone instead of relying on the coordinator node time zone. If the time zone is not specified, it is assumed that you wanted to enter ’00:00:00’ as the time zone.

The default format for displaying timestamp values in the CQL shell is “yyyy-mm-dd HH:mm:ssZ”. This format shows all of the available information about the timestamp value to the user.

Sometimes you will want to update the data that has been written. As in standard SQL database systems, it is possible to update records, but the inner workings of the UPDATE command in Cassandra are a bit different. Let’s change the brand and the model of an offer that user jdoe made on 2014-08-11.

UPDATE offers SET brand = 'Ford', model = 'Mustang' WHERE username = 'jdoe' AND date='2014-08-11 17:12:32+0200'; |

Code Listing 29

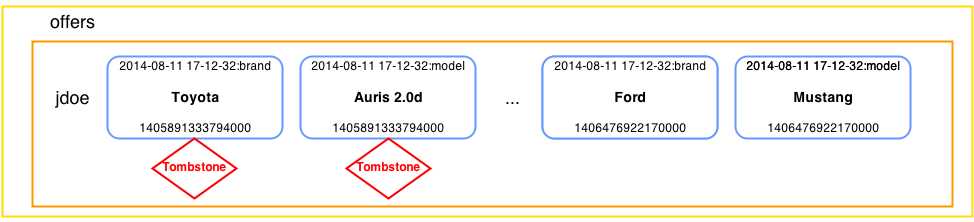

Updating the value actually adds a new column within the row with the new time stamp and marks the old columns with tombstones. The tombstone is not set immediately, the data is just written. With the first read or compaction process starts, Cassandra will compare the two columns. If the column names are the same, the one with a newer time stamp wins. The other columns are marked with tombstones. This is easier to visualize in the following figure.

- Updating columns: The old columns get tombstones, and new columns are added with new values

When manipulating data, there is another important difference when comparing Cassandra to SQL solutions. Let’s review the current table data.

SELECT username, date, brand, model FROM offers; username | date | brand | model ----------+--------------------------+-------+--------- jdoe | 2014-08-11 17:12:32+0200 | Ford | Mustang jdoe | 2014-08-25 11:13:22+0200 | Audi | A3 jsmith | 2014-05-11 01:22:11+0200 | Ford | Orion jsmith | 2014-09-09 11:35:20+0200 | BMW | 118d jsmith | 2014-09-19 11:35:20+0200 | BMW | 120i jsmith | 2014-09-20 17:12:32+0200 | Audi | A6 adoe | 2014-08-26 10:11:10+0200 | VW | Golf |

Code Listing 30

Now, let’s try to insert the first offer from the jdoe user but with a different brand and model.

INSERT INTO offers ( username, date, price, brand, model, year, mileage, color) VALUES ( 'jdoe', '2014-08-11 17:12:32', 7000, 'Toyota', 'Auris 2.0d', 2012, 15000, 'Blue'); |

Code Listing 31

What do you think would be the result of the previous INSERT statement? Well, if this were a classical SQL database, we would probably get an error because the system already has data with the same username and date. Cassandra is a bit different. As mentioned before, INSERT adds new columns and that’s it. The new columns will have the same names as the old ones, but they will have new time stamps. So when reading the data, Cassandra will return the newest columns. After running the previous INSERT statement, running the same query as in Code Listing 30 would return the following.

SELECT username, date, brand, model FROM offers; username | date | brand | model ----------+--------------------------+--------+------------ jdoe | 2014-08-11 17:12:32+0200 | Toyota | Auris 2.0d jdoe | 2014-08-25 11:13:22+0200 | Audi | A3 jsmith | 2014-05-11 01:22:11+0200 | Ford | Orion jsmith | 2014-09-09 11:35:20+0200 | BMW | 118d jsmith | 2014-09-19 11:35:20+0200 | BMW | 120i jsmith | 2014-09-20 17:12:32+0200 | Audi | A6 adoe | 2014-08-26 10:11:10+0200 | VW | Golf |

Code Listing 32

On some occasions you will want to delete data. This is done with the DELETE statement. Usual SQL systems allow the DELETE statement to be called without specifying which rows to delete. This then deletes all the rows in the table. With Cassandra, you must provide the WHERE part of the DELETE statement for it to work, but there are some options. We can always specify just the partition key in the WHERE part. This removes the entire row and, in effect, all of the offers made by the user.

DELETE FROM offers WHERE username = 'maybe'; |

Code Listing 33

The previous statement is a rather dangerous one because it removes the entire row, and it is done with a username that is not present in our example. Usually, when deleting the data, all of the primary key columns are specified, not just the partition (first) key.

DELETE FROM offers |

Code Listing 34

Data Manipulation Corner Cases

In the previous section, we used an INSERT statement using the same partition and clustering key with new data set in the columns instead of updating the row. This technique is called upserting.

Upserting is a very popular technique in Cassandra and is actually the recommended way to update data. It also makes system maintenance and implementation easier because we don’t have to design and implement additional update queries.

Tip: Upsert data by inserting new data with the old key whenever possible.

Upserting data is what you should be doing most of the time in Cassandra, but let’s compare it with inserting. Let’s assume that, for some reason, users can change all of the offers in our example at any time. We will analyze the fields and see what changes are even possible.

It would not be wise to let the system change the username on the offer. This would actually represent a serious security issue if left to any user. For our comparison, we’ll assume that the administrator of the system will be able to change the username. Let’s try changing it.

UPDATE offers SET username = 'maybe' WHERE username = 'jdoe' AND date = '2014-08-11 17:12:32+0200'; Bad Request: PRIMARY KEY part username found in SET part |

Code Listing 35

OK, this didn’t work but while we are at it, let’s try to change the offer date and set it to the day after the offer date with the UPDATE command. The date field is not a partition key. In actuality, it is a clustering key, so it might just work.

UPDATE offers SET date = '2014-08-12 17:12:32+0200' WHERE username = 'jdoe' AND date = '2014-08-11 17:12:32+0200'; Bad Request: PRIMARY KEY part username found in SET part |

Code Listing 36

OK, this didn’t work either. date is also a part of the primary key. You may have expected it because of the error message received in the first try. Updating primary key columns is not possible.

This example is very important to remember. Cassandra does not allow updates to any of the primary key fields.

Note: Cassandra does not allow updates to primary key fields.

If you have some data that might require this kind of update, and if it is data that changes a lot, you might want to consider other storage technologies or move this logic to the application level. This could be done in two steps. The steps are interchangeable; the choice is left to the system designer. Let’s consider an example where the first step is to insert the new data and the second is to delete the old data.

INSERT INTO offers ( username, date, price, brand, model, year, mileage, color) VALUES ('maybe', '2014-08-11 17:12:32', 7000, 'Toyota', 'Auris 2.0d', 2012, 15000, 'Blue'); DELETE FROM offers WHERE username = 'jdoe' AND date = '2014-08-11 17:12:32+0200'; |

Code Listing 37

The database will be in an inconsistent state before the DELETE statement is issued, but the situation would be the same if we reversed the steps. If the INSERT happens before the DELETE, two offers might be visible in the system for a while. If the DELETE happens before the INSERT, an offer might be missing. As mentioned before, it’s up to the system designers to decide which is lesser of the two evils.

The previous case will work just fine in most situations. Still, sometimes it’s possible due to various concurrency techniques that the previous queries won’t run in an order we intended for them. Issuing the previous commands from a shell or from DevCenter will always run in this order, but when the application issues multiple requests, it might lead to inconsistency.

Also, some systems might have clocks that are not 100 percent in sync. If, for instance, the clocks have offsets even in the milliseconds range, it is very important that the commands are issued exactly one after the other. Simply add USING TIMESTAMP <integer> to the statements that you want to run in a specific order. The Cassandra clusters will then use the provided USING TIMESTAMP instead of the time when they received the command. Using this option on an application level will, in most cases, prevent the caching of prepared statements, so use it wisely. Also, note that this option is usually not issued if users give the commands sequentially by typing.

Playing with the TIMESTAMP option might be a little tricky. For instance, if by some mistake we issue a DELETE that is in the future, we might work with an entry normally, and later wonder why it disappeared without having issued a DELETE command.

Anyway, the following code example issues the previous INSERT and DELETE statement combination with the TIMESTAMP option.

INSERT INTO offers ( username, date, price, brand, model, year, mileage, color) VALUES ('jdoe', '2014-08-11 17:12:32+0200', 7000, 'Toyota', 'Auris 2.0d', 2012, 15000, 'Blue') USING TIMESTAMP 1406489822417000; DELETE FROM offers USING TIMESTAMP 1406489822417001 WHERE username = 'jdoe' AND date = '2014-08-11 17:12:32+0200'; |

Code Listing 38

The INSERT statement has the TIMESTAMP option specified at the end. In the DELETE statement, it’s specified before the WHERE part of the statement. The TIMESTAMP option is rarely used, but it is included here because knowing about this option might save you some time when encountering weird issues when manipulating data in Cassandra.

Querying

So far, we’ve spent a lot of time exploring data manipulation because to work with queries, we have to create some data in the database. The command for retrieving data is called SELECT, and it has appeared in a couple of examples in previous sections of the book. For those of you with experience in classical SQL databases, you won’t have any problems adapting to the syntax of the command, but the behavior of the command will probably seem a bit strange. Remember, with Cassandra, the emphasis is on scalability.

There are two key differences when comparing CQL to SQL:

- No JOIN operations are supported.

- No aggregate functions are available other than COUNT.

With classical SQL solutions, it’s possible to join as many tables together as you like and then combine the data to produce various views. In Cassandra, joins are avoided because of scalability. It is a good practice for developers and architects think up-front about what they will want to query and then populate the tables accordingly during the write phase. This will cause a lot of data redundancy, but this is actually a common pattern with Cassandra. Also, we mentioned in a previous chapter that the disk is considered to be the cheapest resource when building applications with Cassandra.

The only allowed aggregate function is COUNT, and it is often used when implementing paging solutions. The important thing to remember with the COUNT function is that it won’t return an actual count value in some cases, and also that this function is restricted with a limit. The most common limit value is 10000, so if the expected count is larger but the function returns exactly 10000, you may need to increase the limit to get the exact value. At the same time, be very careful and bear in mind that this might cause performance issues.

In the previous sections, we discussed the basic SELECT statements and limited ourselves to displaying specific columns because not enough space was available to show all of the table columns nicely. Building the queries was easy because we knew the keyspace names, table names, and column names in the tables. DevCenter makes this easier because of the graphical interface, but for those of you using the CQL shell, the situation requires a couple of commands to find your way around. The most useful command is DESCRIBE. As soon as you connect to Cassandra with the CQL shell, you can issue the following command.

cqlsh> DESCRIBE keyspaces; system used_cars system_traces cqlsh> |

Code Listing 39

Now we see our used_car keyspace is available and we can issue the USE command on it. Now that we are in the used_cars keyspace, it would be nice if we could see what tables are available. We can use the DESCRIBE command with the tables parameter to do just that.

cqlsh> DESCRIBE tables; Keyspace system --------------- IndexInfo hints range_xfers NodeIdInfo local schema_columnfamilies batchlog paxos schema_columns compaction_history peer_events schema_keyspaces compactions_in_progress peers schema_triggers sstable_activity Keyspace used_cars ------------------ offers_by_brand test_comments offers test_data users Keyspace system_traces ---------------------- events sessions cqlsh> |

Code Listing 40

Using the DESCRIBE command with the tables parameter gave us a list of tables. Most of the tables in the previous listing are system tables; we usually won’t have any direct interaction with them through CQL. Now that we have a list of tables in the used_cars keyspace, it would be very interesting for us to see the columns in the table and their types. Let’s look it up for the offers table.

cqlsh:used_cars> DESCRIBE TABLE offers; CREATE TABLE offers ( username text, date timestamp, brand text, color text, mileage int, model text, price float, year int, PRIMARY KEY ((username), date) ) WITH bloom_filter_fp_chance=0.010000 AND caching='KEYS_ONLY' AND comment='' AND dclocal_read_repair_chance=0.100000 AND gc_grace_seconds=864000 AND index_interval=128 AND read_repair_chance=0.000000 AND replicate_on_write='true' AND populate_io_cache_on_flush='false' AND default_time_to_live=0 AND speculative_retry='99.0PERCENTILE' AND memtable_flush_period_in_ms=0 AND compaction={'class': 'SizeTieredCompactionStrategy'} AND compression={'sstable_compression': 'LZ4Compressor'}; cqlsh:used_cars> |

Code Listing 41

The most interesting result of the previous command is column names and their types. If you want to optimize and tweak the table behavior, you will probably use this command to check if a setting was successfully applied to the table. Let’s check the current state in the offers table.

SELECT username, date, brand, model FROM offers; username | date | brand | model ----------+--------------------------+-------+------- jdoe | 2014-08-25 11:13:22+0200 | Audi | A3 jsmith | 2014-05-11 01:22:11+0200 | Ford | Orion jsmith | 2014-09-09 11:35:20+0200 | BMW | 118d jsmith | 2014-09-19 11:35:20+0200 | BMW | 120i jsmith | 2014-09-20 17:12:32+0200 | Audi | A6 adoe | 2014-08-26 10:11:10+0200 | VW | Golf |

Code Listing 42

It would be very interesting for us to see only the offers from a specific user. Since the user jsmith has the most offers, let’s concentrate on them. Picking their offers will be done with the WHERE clause and specifying the jsmith username.

SELECT username, date, brand, model FROM offers WHERE username = 'jsmith'; username | date | brand | model ----------+--------------------------+-------+------- jsmith | 2014-05-11 01:22:11+0200 | Ford | Orion jsmith | 2014-09-09 11:35:20+0200 | BMW | 118d jsmith | 2014-09-19 11:35:20+0200 | BMW | 120i jsmith | 2014-09-20 17:12:32+0200 | Audi | A6 |

Code Listing 43

You might want to filter the offers table for multiple users and build a query that would return all of the offers for users jsmith and adoe.

SELECT username, date, brand, model FROM offers WHERE username = 'jsmith' OR username = 'adoe'; Bad Request: line 1:74 missing EOF at 'OR' |

Code Listing 44

The OR operator does not exist in Cassandra. If we want to select multiple offers from the users, we have to use the IN operator.

SELECT username, date, brand, model FROM offers WHERE username IN ('jsmith', 'adoe'); username | date | brand | model ----------+--------------------------+-------+------- jsmith | 2014-05-11 01:22:11+0200 | Ford | Orion jsmith | 2014-09-09 11:35:20+0200 | BMW | 118d jsmith | 2014-09-19 11:35:20+0200 | BMW | 120i jsmith | 2014-09-20 17:12:32+0200 | Audi | A6 adoe | 2014-08-26 10:11:10+0200 | VW | Golf |

Code Listing 45

We’ll concentrate on the offers from the jsmith user again and select the offer that the user made on a specific date. Remember, the offer is identified by the combination of the username and the date information for the offer. If you go back to the previous section, you will find that the username and date information form a primary key. The query is:

SELECT username, date, brand, model FROM offers WHERE username= 'jsmith' AND date = '2014-09-09 11:35:20+0200'; username | date | brand | model ----------+--------------------------+-------+------- jsmith | 2014-09-09 11:35:20+0200 | BMW | 118d |

Code Listing 46

If we would like to get two specific orders for the user from the table, we could again use the IN operator as shown in the following example.

SELECT username, date, brand, model FROM offers WHERE username= 'jsmith' AND date IN ('2014-09-09 11:35:20+0200', '2014-09-19 11:35:20+0200'); username | date | brand | model ----------+--------------------------+-------+------- jsmith | 2014-09-09 11:35:20+0200 | BMW | 118d jsmith | 2014-09-19 11:35:20+0200 | BMW | 120i |

Code Listing 47

But listing all of the dates to get the offers from the user is not the most efficient way to query the data. Think about it; we would actually have to know every piece of data in the list in order to get the listing. A more practice-oriented query would be to show all of the offers made by the user since a certain time or all of the offers made within a period of time. Let’s look at the offers jsmith did in September.

SELECT username, date, brand, model FROM offers WHERE username= 'jsmith' AND date > '2014-09-01' AND date < '2014-10-01'; username | date | brand | model ----------+--------------------------+-------+------- jsmith | 2014-09-09 11:35:20+0200 | BMW | 118d jsmith | 2014-09-19 11:35:20+0200 | BMW | 120i jsmith | 2014-09-20 17:12:32+0200 | Audi | A6 |

Code Listing 48

Some might set the end date to be ‘2014-09-30’, but this would not return offers made on the last day of the month because CQL, by default, assumes the values for hours, minutes, and seconds are set to zero. So, specifying the 30th would, in effect, ignore all of the offers after midnight, or in other words, all the offers for that day.

The simplest way to approach this is to specify the first day of the following month as the end date with the less than operator. The previous query is not 100 percent correct, actually. The offers made between the stroke of midnight and the expiration of the first millisecond will not be included in the results. To cover this case, simply add the equal sign after the greater-than sign. The comparison operators are not always possible in Cassandra. Cassandra will allow comparison operators only in the situations where it can retrieve data sequentially.

In previous examples, all of the offers from the user are automatically sorted by their date by Cassandra. That’s why we could use the greater-than and less-than operators. We did this on the clustering part of the primary key. Now, just for a moment, let’s take a small step back and try some sort of comparison with the first part of the primary key. We will create a whole new table to do that, just to show the situation for the numbers:

CREATE TABLE test_comparison_num_part ( a int, b text, PRIMARY KEY (a) ); INSERT INTO test_comparison_num_part (a, b) VALUES (1, 'A1'); INSERT INTO test_comparison_num_part (a, b) VALUES (2, 'A2'); INSERT INTO test_comparison_num_part (a, b) VALUES (3, 'A3'); INSERT INTO test_comparison_num_part (a, b) VALUES (4, 'A4'); SELECT * FROM test_comparison_num_part WHERE a >= 3; Bad Request: Only EQ and IN relation are supported on the partition key (unless you use the token() function) |

Code Listing 49

As the previous error message says, the first part of the primary key can only be retrieved with the equal sign and an IN operator. This is one of Cassandra’s limitations when it comes to querying the data. Let’s look into the other parts of the primary key. We will create a new and independent example to show Cassandra’s behavior in this case.

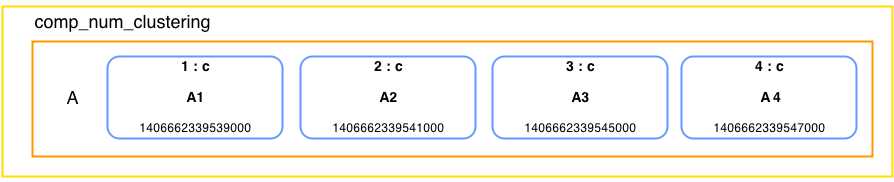

CREATE TABLE comp_num_clustering ( a text, b int, c text, PRIMARY KEY (a, b) ); INSERT INTO comp_num_clustering (a, b, c) VALUES ('A', 1, 'A1'); INSERT INTO comp_num_clustering (a, b, c) VALUES ('A', 2, 'A2'); INSERT INTO comp_num_clustering (a, b, c) VALUES ('A', 3, 'A3'); INSERT INTO comp_num_clustering (a, b, c) VALUES ('A', 4, 'A4'); SELECT * FROM comp_num_clustering WHERE a = 'A' AND b > 2; a | b | c ---+---+---- A | 3 | A3 A | 4 | A4 |

Code Listing 50

The previous results look just fine. We specified what row we wanted to read and provided the range. Cassandra can find the row, do the sequential read of it, and then return it to us. This is possible because the values from column b actually become columns. So, in row A we don’t have columns called b, but we have columns called 1:c, 2:c, etc., and the values in those columns are A1, A2, etc.

I’m reviewing how Cassandra stores tables because it is very important to understand the internals of Cassandra in order to use them as efficiently as possible.

- Cassandra storage of the table in Code Listing 50

Everything is fine with the ranges, but what would happen if we tried this on multiple rows? What if we wanted all of the data where b is greater than some number, let’s say, 3?

SELECT * FROM comp_num_clustering WHERE b >= 3; Bad Request: Cannot execute this query as it might involve data filtering and thus may have unpredictable performance. If you want to execute this query despite the performance unpredictability, use ALLOW FILTERING |

Code Listing 51

This might seem a bit unexpected, especially to people coming from the relational world. The numbers are ordered so why we are not getting all of the data out? Well, the previous table might have multiple rows. In order to find all the data, the client would have to potentially contact other nodes, wait for their results, go through every row that it receives, and then read the data out of them. This simple query could very easily contact every node in the cluster and cause serious performance degradation. In Cassandra, everything is oriented toward performance. So, that kind of querying is not possible out of the box or even allowed in some cases. One way of making this kind of querying possible is with the ALLOW FILTERING option. The following query would return the results just as we might expect them.

SELECT * FROM comp_num_clustering WHERE b >= 3 ALLOW FILTERING; a | b | c ---+---+---- A | 3 | A3 A | 4 | A4 |

Code Listing 52

ALLOW FILTERING will let you run some queries that might require filtering. Use this option with extreme caution. It significantly degrades performance and should be avoided in production environments. The main disadvantage of the filtering is that it usually involves a lot of queries to other nodes and, if done on big tables, it may cause very long processing times that are pretty nondeterministic. While we are at it, let’s try the filtering option for column c.

SELECT * FROM comp_num_clustering WHERE c = 'A4' ALLOW FILTERING; Bad Request: No indexed columns present in by-columns clause with Equal operator |

Code Listing 53

Indexes

The filtering option does not give us the ability to search the table by the data in the c column. The error message warns us that there are no indexed columns, so let’s create an index in the table for the c column.

CREATE INDEX ON comp_num_clustering(c); SELECT * FROM comp_num_clustering WHERE c = 'A4'; a | b | c ---+---+---- A | 4 | A4 |

Code Listing 54

The previous query returned the results once we created the index on the column. Creating indexes might seem the easy way to add searching capabilities to Cassandra. Theoretically, we could create an index on the table any time we needed to search for any kind of data, but creating indexes has some potentially dangerous downsides.

Cassandra stores the indexes just as it stores the other tables. The indexed value becomes the partition key. Usually, the more unique values there are, the better the index performance. On the other hand, maintaining this index will be a significant overhead for the system if the number of rows grows because every node will have to have most of the information that the other nodes store. The other possibility is that we have some binary index with some sort of true-false values. This would be an index with a very small number of unique values. That kind of index quickly gets many columns in just a couple of rows and becomes unresponsive over time because it is searching within the two very large rows. One important point is that if the node fails and we restore the data, the index will have to be rebuilt from scratch. As a rule of thumb, the best use for indexes is on relatively small tables with queries that return results in tens or hundreds but not more.

The index that we created in the previous example returned an automatic name because we simply forgot to specify a name for it. This is a very common mistake. Indexes are updated on every write to Cassandra and there are techniques that eliminate the need for them, so if we at some point in time decide to remove the index, we will run into trouble because we have to know its name in order to remove it. The following query makes it possible for us to find the index name together with other information that is relevant for identifying it.

SELECT column_name, index_name, index_type FROM system.schema_columns WHERE keyspace_name='used_cars' AND columnfamily_name='comp_num_clustering'; column_name | index_name | index_type -------------+---------------------------+------------ a | null | null b | null | null c | comp_num_clustering_c_idx | COMPOSITES |

Code Listing 55

We have made an index in the c column of the comp_num_clustering table, so the index that we are looking for must be the last index in the table shown after running the previous query. The following example shows how to remove the index.

DROP INDEX comp_num_clustering_c_idx; |

Code Listing 56

The previous index name seems pretty reasonable, and from the name we can determine what this index is all about. If you don’t like the naming Cassandra does automatically, or you have some special naming convention that you have to enforce, then you can do name the index with the following command.

CREATE INDEX comp_num_clustering_c_idx ON comp_num_clustering(c); |

Code Listing 57

This way, you can keep the index name in the initialization scripts for other nodes or development environments and avoid depending on the automatic index naming that might change in future versions of Cassandra.

Now that you know how Cassandra fetches data and that it’s not always possible to get data with any column value out, let’s look at the ORDER BY clause. Using this clause is not always possible. Most relational databases allow combinations of multiple columns on almost all queries. Cassandra limits this for performance gains. ORDER BY can be specified on one column only, and that column has to be the second key from the primary key specification. On the comp_num_clustering table, it’s the b column; in the offers, it is the date column. Two possible orders are ASC and DESC. As an example, we will reverse the jsmith user’s offers in time and put them in descending order. They are ascending by default because Cassandra sorts by column names, so there is no need to use ASC on the offers table.

SELECT username, date, brand, model FROM offers WHERE username= 'jsmith' ORDER BY date DESC; username | date | brand | model ----------+--------------------------+-------+------- jsmith | 2014-09-20 17:12:32+0200 | Audi | A6 jsmith | 2014-09-19 11:35:20+0200 | BMW | 120i jsmith | 2014-09-09 11:35:20+0200 | BMW | 118d jsmith | 2014-05-11 01:22:11+0200 | Ford | Orion |

Code Listing 58

ORDER BY is not used often. It’s more common to specify the clustering option when creating the table so that the data is automatically retrieved in the order that the system designers intended it. Most of the time, ordering is based on some kind of time-based column like a sensor, user activity, weather, or some other readings.

Collections

The primary use for collections in Cassandra is storing a small amount of denormalized data together with the basic set of information. The most common usages for collections are storing e-mails, storing properties of device readings, storing properties of events that are variable from occurrence to occurrence, and so on. Cassandra limits the amount of elements in a collection to 65,535 entries. You can insert data past this limit but the data is preserved and managed by Cassandra only up to the limit. There are three basic collection types:

- map

- set

- list

These structures are pretty common in most programming languages today, and most readers will have at least a basic understanding of them. We’ll show each structure with a couple of examples, and while we’re at it, we’ll expand our data model a bit and make use of the collections.

We’ll start with the map collection in our used car example. By now, we have defined the offers table and specified some basic offer attributes such as date, brand, color, mileage, model, price, and year. Now, we know that different cars have very different accessories in them. Some cars might run on different fuels, have different transmissions, or have different numbers of doors. We could cover all these extra properties without adding new columns to our offers table if we specified a map type column in the offers table as shown in the following example.

ALTER TABLE offers ADD equipment map<text, text>; |

Code Listing 59

Now that we have the equipment map on our offers, let’s talk a bit about the properties of the map collection. Long story short, a map is a typed set of key-value pairs. The keys in the map are always unique. One interesting property of the values in a map when stored in Cassandra is that the keys are always sorted.

There are two ways to define map key-value pairs. One is to update just the specific key in the map. The other is to define a whole map at once. Both ways are possible with the UPDATE command, but when using INSERT, you can specify just the whole map. Let’s see what an INSERT would look like.

INSERT INTO offers ( username, date, price, brand, model, year, mileage, color, equipment) VALUES ('adoe', '2014-09-01 12:02:52', 12000, 'Audi', 'A4 2.0T', 2008, 99000, 'Black', { 'transmission' : 'automatic', 'doors' : '4', 'fuel' : 'petrol' }); |

Code Listing 60

The syntax for defining the maps is pretty similar to the very popular JSON format. The comma separates the key-value pairs and the key is separated from the value by a colon. The saved row looks like the following.

SELECT equipment FROM offers WHERE username= 'adoe'; equipment --------------------------------------------------------------- {'doors': '4', 'fuel': 'petrol', 'transmission': 'automatic'} |

Code Listing 61

Notice that the stored map values are sorted and that they don’t depend on the order we defined them. If we ever decide to change the values in the map or add a new one without discarding the old values, we can use the following UPDATE commands.

UPDATE offers SET equipment['doors'] = '5', equipment['turbo'] = 'yes' WHERE username = 'adoe' AND date='2014-09-01 12:02:52'; |

Code Listing 62

The previous query will update the doors key in the map and will add a new turbo key to it. This syntax is used when doing updates because we don’t have to care if the key was created or not. We simply specify its value and Cassandra will update the key with the new value if it is able to find it, or it will define a new key if it’s unable to find it. Let’s see what the data looks like at the moment.

SELECT equipment FROM offers WHERE username= 'adoe'; equipment --------------------------------------------------------------- {'doors': '5', 'fuel': 'petrol', 'transmission': 'automatic', 'turbo': 'yes'} |

Code Listing 63

If we wanted to redefine the complete map, we would simply set equipment to be equal to a whole new map definition as it was done in Code Listing 60. Still, sometimes we will want to remove just specific keys from the map. This is done with the DELETE command.

DELETE equipment['turbo'] FROM offers WHERE username = 'adoe' AND date='2014-09-01 12:02:52+0200'; |

Code Listing 64

Deleting a key that does not exist in the map is not a problem. You can run the previous example as many times as you like but it will delete the turbo key only on the first run. We have yet to cover the concept of time to live (TTL). For now, just remember that Cassandra can automatically delete data after it has lived for a specified period of time. For instance, if you insert or update a key-value with a time to live parameter, the time the data will actually live refers only to the changed, inserted key-value pair. All the other data have their own times to live. We will discuss the TTL concept more in depth later. For now, it’s enough to know that collections specify a TTL on an element level, not on the row or the column level.

The next collection type we are going to dive into is the set. A set is a collection of unique values. Cassandra always orders sets by their value. Creating a column that is a set is done with the set keyword followed by the type of key elements in angled brackets. One of the most common uses for sets is saving user contact data such as e-mail addresses and phone numbers. Let’s add a set of e-mails to the users table.

ALTER TABLE users ADD emails set<text>; |

Code Listing 65

Now the users table can store more e-mails for every user. Inserting a new user is shown in the following example.

INSERT INTO users ( username, password, first_name, last_name, state, emails) VALUES ('jqpublic', 'secret', 'John', 'Public', 'NY', {'[email protected]', '[email protected]'}); |

Code Listing 66

The difference in sets when compared to maps is that there are no key elements, there are just values. If you add duplicates in the previous e-mail list, the duplicated values will not be stored in Cassandra. The values in the set are always sorted just as the keys in maps are.

The updating syntax is based on the plus and minus operators. If we wanted to first remove an e-mail address from the set and then add a new one, we would do it with the following queries.

UPDATE users SET emails = emails - {'[email protected]'} WHERE username = 'jqpublic'; UPDATE users SET emails = emails + {'[email protected]'} WHERE username = 'jqpublic'; |

Code Listing 67

The previous queries result in the following emails for the user jqpublic.

SELECT username, emails FROM users WHERE username = 'jqpublic'; username | emails ----------+------------------------------------- jqpublic | {'[email protected]', '[email protected]'} |

Code Listing 68

The last collection type in Cassandra is a list. A list is a typed collection of non-unique values. The values in the list are ordered by their position. Map and set values are always sorted. The list elements always remain in the position where we put them. The most basic example would be a to-do list. We’ll show how to use the list in the next examples. Before doing anything with the list, we have to define one.

CREATE TABLE list_example ( username text, to_do list<text>, PRIMARY KEY (username) ); |

Code Listing 69

Maps and sets are set in braces, but the list is in brackets. Other than that, the list is pretty similar to the previous two collection types. Let’s see how to define a list when inserting data into a table.

INSERT INTO list_example (username, to_do) VALUES ('test_user', ['buy milk', 'send mail', 'make a call']); |

Code Listing 70

The previous INSERT statement generated a simple to-do list for a user, with three elements in it. Let’s have a look at what’s in the table.

SELECT * FROM list_example; username | to_do -----------+------------------------------------------ test_user | ['buy milk', 'send mail', 'make a call'] |

Code Listing 71

When referencing the elements in the list, we do so by their position. The first element in the list has the position 0, the second 1, and so on. The following example shows how to update the first element in the to-do list of the user.

UPDATE list_example SET to_do[0] = 'buy coffee' WHERE username = 'test_user'; |

Code Listing 72

In some situations, we will want to add elements to the list.

UPDATE list_example SET to_do = to_do + ['go to a meeting', 'visit parents'] WHERE username = 'test_user'; |

Code Listing 73

Cassandra can also remove occurrences of items from the list.

UPDATE list_example SET to_do = to_do - ['send mail', 'make a call'] WHERE username = 'test_user'; |

Code Listing 74

It’s also possible to delete elements with a specific index in the list.

DELETE to_do[1] FROM list_example WHERE username = 'test_user'; |

Code Listing 75

All of the previous changes in the list should result in the following.

SELECT * FROM list_example; username | to_do -----------+--------------------------------- test_user | ['buy coffee', 'visit parents'] |

Code Listing 76

Now we know how to use collections in Cassandra. Collections are a relatively new concept in Cassandra. They are very useful in many day-to-day situations. Because they are very easy to work with, they might sometimes be overused. Be very careful and don’t fill up collection columns with data that might be in the tables. All of the collection types are limited to 65,535 elements; having more would definitely be a sign that you are doing something wrong.

Time Series Data in Cassandra

Knowing how something changes over time is always important. By having the historical data about some kind of phenomenon, we can draw conclusions about the inner workings of that phenomenon and then predict how it’s going to behave in the future. When talking about historical data, it usually consists of a measurement and a time stamp of when the measurement was taken. In statistics, these measurements are called data points. If the data points are in sequence, and if the measurements are spaced at uniform time intervals, then we are talking about time series data.

Time series data is very important in many fields of human interest. It is often used in:

- Performance metrics

- Fleet tracking

- Sensor data

- System logging

- User activity and behavior tracking

- Financial markets

- Scientific experiments

The importance of time series data is growing even more in today’s world of interconnected devices that are getting smarter and, therefore, generate more and more data. Time series data is often associated with terms such as the Internet of Things (IoT). Every day, there are more devices generating more data. Until recently, most of this time series data was gathered on very specialized and expensive machines which, more or less, supported only vertical scaling. There aren’t a lot of storage solutions out there that can handle large amounts of data and allow horizontal scaling at the same time. As a storage technology, Cassandra’s performance is very comparable to expensive and specialized solutions; it even outperforms them in some areas.

So far we have gone pretty deep into some concepts of Cassandra, and we know that columns in Cassandra rows are always sorted by the column name. We also learned that Cassandra, in some cases, uses logical row values to form column names for the data that is going to be stored. Cassandra usually stores time series data presorted and fetches it with very little seeking on the hard drive.

We have also looked at modeling examples in our online used car market. When interacting with time series data, however, most tutorials use weather station data. We will also be using weather stations to introduce time series data because they use easy to understand concepts. Weather stations usually measure barometric pressure and the amount of precipitation, but we will limit all of our examples to temperature only to keep things simple.

Basic Time Series

Cassandra can support up to two billion columns in a single row. If you have a temperature measurement captured on a daily or hourly basis, a single row for every weather station will be enough. Each row in this table would probably be marked with some kind of weather station ID. The column name would be the time stamp of when the measurement was taken, and the data would be the temperature.

Let’s place the time series examples into a separate keyspace. We will come back to the used cars in the later sections.

CREATE KEYSPACE weather WITH replication = { 'class': 'SimpleStrategy', 'replication_factor' : 1}; |

Code Listing 77

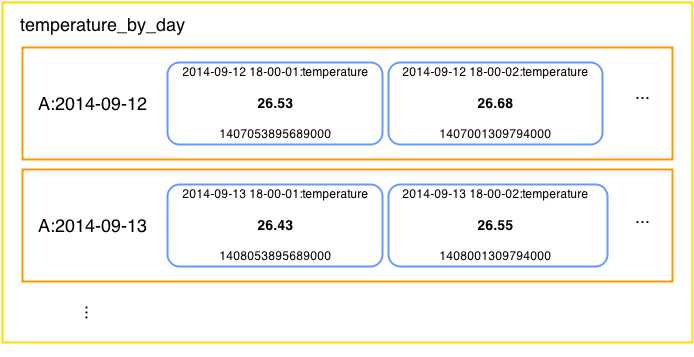

In its simplest form, basic weather station data could be gathered with the following table.

CREATE TABLE temperature ( weatherstation_id text, measurement_time timestamp, temperature float, PRIMARY KEY (weatherstation_id, measurement_time) ); |

Code Listing 78

If the data is gathered every hour per year, one weather station would generate around 8,760 columns. Even if we added additional data to the previous table, the column number would not pass Cassandra’s row length limitation in even the most optimistic predictions for the system’s expected lifetime. Adding temperature readings to this table is shown in the following example.

INSERT INTO temperature (weatherstation_id, measurement_time, temperature) VALUES ('A', '2014-09-12 18:00:00', 26.53); |

Code Listing 79

Feel free to add as many readings to the temperature table as you like. All of the inserted data will be saved under a weather station row. Column names will be the measurement time stamps, and temperatures will be the stored values. Let’s look at how Cassandra stores this data internally.

- Single weather station data

In our temperature example, Cassandra will automatically sort all of the inserted data by the measurement time stamp. This makes reading the data very fast and efficient. When loading the data, Cassandra reads portions on the disk sequentially and this is where most of the efficiency and speed comes from.

Sooner or later, we will need to perform some kind of analysis on time series data. To do it in our example, we will fetch the temperature measurement data station by station. Fetching all of the temperature readings from weather station A would be done with the following query.

SELECT * FROM temperature WHERE weatherstation_id = 'A'; weatherstation_id | measurement_time | temperature -------------------+--------------------------+------------- A | 2014-09-12 18:00:00+0200 | 26.53 A | 2014-09-12 19:00:00+0200 | 26.68 A | 2014-09-12 20:00:00+0200 | 26.98 A | 2014-09-12 21:00:00+0200 | 22.11 |

Code Listing 80

If the application gathers data for a very long time, the amount of data in a row might become too impractical to be analyzed in a timely manner. Also, Cassandra is, in most cases, primarily used for storing and organizing the data. Almost any kind of analysis would have to be done on an application level since Cassandra does not have any aggregating functions other than COUNT. In reality, most of the analysis will not require you to fetch all of the data that was ever recorded by the weather station. In fact, most analysis will be for certain periods of time, such as a day, week, month, or year. To limit the results down to a specified period, the following query is used.

SELECT measurement_time, temperature FROM temperature WHERE weatherstation_id = 'A' AND measurement_time >= '2014-09-12 18:00:00' AND measurement_time <= '2014-09-12 20:00:00'; weatherstation_id | measurement_time | temperature -------------------+--------------------------+------------- A | 2014-09-12 18:00:00+0200 | 26.53 A | 2014-09-12 19:00:00+0200 | 26.68 A | 2014-09-12 20:00:00+0200 | 26.98 |

Code Listing 81

Note that if we ran the previous query without the greater than or equal to operator and used just the greater than operator, we would not include the readings for the time stamps that we specified in the query conditions. Sometimes this might lead to a faulty analysis or unexpected results.

Our weather station example will handle most basic time series usages. As you might have noticed, Cassandra gets along with time series data pretty easily, and running it enables horizontal scaling and reasonable running costs.

Reverse Order Time Series

In some cases, applications will be oriented toward recent data, and fetching historical data will not be as important. We know that Cassandra always sorts columns. So, if we selected just a few results from our weather station row, we would get the first results the weather station ever recorded. This is not very useful in dashboard-like applications where we just want to see the latest results. Furthermore, the old data might even be irrelevant to us, and we would want to remove it completely from our storage.

Cassandra handles this case very well because we can influence the way Cassandra stores and sorts a row in the table with the help of the CLUSTERING directive when defining the table. We talked about clustering in earlier sections of the book and we also looked at examples of it. Clustering is very important to creating a reverse order time series because it helps increase efficiency, especially if the data is kept for a longer period of time. In our example, we simply need to define a descending clustering on the temperatures table.

CREATE TABLE latest_temperatures ( weatherstation_id text, measurement_time timestamp, temperature float, PRIMARY KEY (weatherstation_id, measurement_time) ) WITH CLUSTERING ORDER BY (measurement_time DESC); |

Code Listing 82

Inserting the data is the same as it was in the temperatures table.

INSERT INTO latest_temperatures (weatherstation_id, measurement_time, temperature) VALUES ('A', '2014-09-12 18:00:00', 26.53); |

Code Listing 83

When we retrieve the values, the latest data will automatically be on top.

SELECT * FROM latest_temperatures WHERE weatherstation_id = 'A'; weatherstation_id | measurement_time | temperature -------------------+--------------------------+------------- A | 2014-09-12 21:00:00+0200 | 22.11 A | 2014-09-12 20:00:00+0200 | 26.98 A | 2014-09-12 19:00:00+0200 | 26.68 A | 2014-09-12 18:00:00+0200 | 26.53 |

Code Listing 84

A query that returns the latest reading of a temperature from the station would look like the following.

SELECT * FROM latest_temperatures WHERE weatherstation_id = 'A' LIMIT 1; weatherstation_id | measurement_time | temperature -------------------+--------------------------+------------- A | 2014-09-12 21:00:00+0200 | 22.11 |

Code Listing 85

We used a LIMIT option to fetch just one result. If we were interested in more than one of the latest readings, we would adjust the limit. All of the other queries are the same as in the basic time series. We could even use the basic time series and then use the ORDER clause to fetch the latest result. The following query uses temperature table, not latest_temperatures.

SELECT * FROM temperature WHERE weatherstation_id = 'A' ORDER BY measurement_time DESC LIMIT 1; weatherstation_id | measurement_time | temperature -------------------+--------------------------+------------- A | 2014-09-12 21:00:00+0200 | 22.11 |

Code Listing 86