CHAPTER 3

Stateful Patterns with Durable Functions

In this chapter, we will discover other fundamental patterns you can implement using Azure Durable Functions. Each of these is managed by the platform precisely in the same way you see for the function chaining pattern. The Durable Functions platform uses the underlying storage to manage each orchestrator's current state and drive the orchestration between the activities.

Fan-out/fan-in

In the fan-out/fan-in pattern, you must execute several activity functions in parallel and wait for all functions to finish (because, for example, you have to aggregate the results received from them in a single value).

Let’s look at an example. Suppose you want to implement a durable function that implements a backup of a disk folder into a blob storage. In this scenario, you retrieve all the files contained in the source folder, and then, for each file, you copy it to the backup folder in the destination storage. You’ll need to run several functions that implement the copy based on the number of files you find in the source folder.

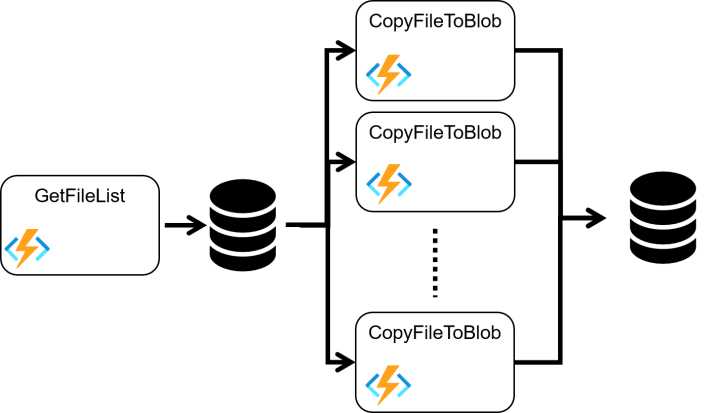

The following image shows you the scenario.

Figure 22: Fan-out/fan-in

The backup client starts the orchestrator, and the orchestrator calls the following activities:

- GetFileList: Retrieves the file list in the source folder and returns it to the orchestrator.

- CopyFileToBlog: Receives the reference to the file to back up in the destination blob and executes the copy. It will run for each file retrieved in the previous one.

Suppose we try to implement a pattern like this using standard Azure Functions. In that case, we can meet all the difficulties we encountered in the function chaining pattern, and we also have another big obstacle.

Calling multiple activities is relatively simple. For example, you can use a queue and publish one message for each function you want to invoke. But waiting for all the activities executed to finish is too hard. How can you manage the status of all the activities in parallel? You need to know exactly the work progress because when all of these finish their jobs, you need to complete your workflow with the results aggregation.

The Durable Functions platform manages all the work progress of the activity functions for you. It can continue your workflow when all of the activities finish their jobs.

In the following snippet of code, you can see the client function.

Code Listing 11: Fan-out/fan-in client function

[FunctionName("Backup_Client")] public async Task<HttpResponseMessage> Client( [HttpTrigger(AuthorizationLevel.Function, "post", Route = "funoutfanin/backup")] HttpRequestMessage req, [DurableClient] IDurableOrchestrationClient starter, ILogger log) { log.LogInformation($"[CLIENT Backup_Client] --> Backup started!"); string jsonContent = await req.Content.ReadAsStringAsync(); try { var backupRequest = JsonConvert.DeserializeObject<BackupRequest>(jsonContent); if (backupRequest.IsValid()) { var instanceId = await starter.StartNewAsync("Backup_Orchestrator", backupRequest); log.LogInformation($"Backup started - started orchestration with ID = '{instanceId}'."); return starter.CreateCheckStatusResponse(req, instanceId); } } catch (Exception ex) { log.LogError("Error during backup operation", ex); } return new HttpResponseMessage(System.Net.HttpStatusCode.BadRequest); } |

The client manages a POST request and supposes that it contains the BackupRequest object based on the JSON schema.

Code Listing 12: The backup request object schema

{ "path":"c:\\temp" } |

The client starts a new orchestrator, passing the backup request, and the orchestrator looks like the following.

Code Listing 13: Fan-out/fan-in orchestrator function

[FunctionName("Backup_Orchestrator")] public async Task<BackupReport> Orchestrator( [OrchestrationTrigger] IDurableOrchestrationContext context, ILogger log) { log.LogInformation($"[ORCHESTRATOR Backup_Orchestrator] --> id : {context.InstanceId}"); var backupRequest = context.GetInput<BackupRequest>(); var report = new BackupReport(); var files = await context.CallActivityAsync<string[]>("Backup_GetFileList", backupRequest.path); report.NumberOfFiles = files.Length; var tasks = new Task<long>[files.Length]; for (int i = 0; i < files.Length; i++) { tasks[i] = context.CallActivityAsync<long>("Backup_CopyFileToBlob", files[i]); } await Task.WhenAll(tasks); report.TotalBytes = tasks.Sum(t => t.Result); return report; } |

The orchestrator executes the following steps:

- Calls the activity Backup_GetFileList, passing the path to backup and saving the file list found in the source folder (the activity returns the list).

- For each file in the file list, the orchestrator creates a Task object to invoke the activity that copies the file in the destination storage. The orchestrator saves all the tasks in an array.

- Leverages the WhenAll method of the Task class to invoke all the activity. That method finishes when all the tasks in the array finish. This means the orchestrator waits for all the activities to complete.

- Adds all the results returned by every activity (the copy activity returns the number of bytes copied) to calculate the number of bytes copied during the backup. The Result property stores the return value of the activity.

You can find the code for the GetFileList activity in the following snippets of code.

Code Listing 14: GetFileList activity

[FunctionName("Backup_GetFileList")] public string[] GetFileList([ActivityTrigger] string rootPath, ILogger log) { log.LogInformation($"[ACTIVITY Backup_GetFileList] --> rootPath : {rootPath}"); string[] files = Directory.GetFiles(rootPath, "*", SearchOption.AllDirectories); return files; } |

The activity receives the disk path from the orchestrator and uses the Directory class to retrieve the list of files in the folder (in a recursive way).

You can improve the function using a complex object in the signature instead of the simple file path. Using a complex object, you can introduce a set of file filters or a flag that allows you to manage the recursion. We have kept the sample as easy as possible for demo purposes.

The following snippet of code shows the CopyFileToBlob activity.

Code Listing 15: CopyFileToBlob activity

[FunctionName("Backup_CopyFileToBlob")] [StorageAccount("StorageAccount")] public async Task<long> CopyFileToBlob([ActivityTrigger] string filePath, IBinder binder, ILogger log) { log.LogInformation($"[ACTIVITY Backup_CopyFileToBlob] --> filePath : {filePath}"); long byteCount = new FileInfo(filePath).Length; string blobPath = filePath .Substring(Path.GetPathRoot(filePath).Length) .Replace('\\', '/'); string outputLocation = $"backups/{blobPath}"; using (Stream source = File.Open(filePath, FileMode.Open, FileAccess.Read, FileShare.Read)) using (Stream destination = await binder.BindAsync<CloudBlobStream>( new BlobAttribute(outputLocation, FileAccess.Write))) { await source.CopyToAsync(destination); } return byteCount; } |

The activity receives the file path from the orchestrator. Then, it uses the FileInfo class to access the file content and copy it (using the dynamic binding provided by the IBinder interface) to the destination.

The IBinder interface is an example of dynamic binding in Azure Functions (it is also called imperative approach). This technique allows you to create the binding connection during the runtime phase instead of having the binding declared in the attributes. Thus, you can use it if you need to change the destination service at runtime. Using this approach, you can, for example, choose to connect to a storage blog or to a storage queue every time the function is executed.

The StorageAccount attribute decorates the activity. It tells the platform that the function uses the storage account defined in the connection string called StorageAccount stored in the configuration file. The function also recreates, within the backup storage, the same folder hierarchy present in the source folder.

Async HTTP APIs

One of the most common scenarios when you have a workflow, especially if your workflow is a long-running operation, is to provide a set of APIs to your users that they can use to retrieve the status of the single workflow instance.

An example might be when you need to notify someone that a workflow finished its job.

In the previous chapter, we looked at how the Durable function manages the state. You could access the underlying persistence layer and read the current status. If you are using a storage account as a persistence layer, you must read the TaskHubInstances table to understand the current state of an orchestrator instance.

Unfortunately, reading the underlying persistence layer is not a good approach, because you are coupled to the persistence schema. You need to modify your code (and retest it) every time something changes in the Durable Function platform.

Fortunately, the scenario is simpler than you might think, because the Durable Function platform provides you with a set of rest APIs you can use to read the status of your orchestration.

Let’s consider the function chaining example we saw in the previous chapter to understand what kind of APIs Durable Functions gives you.

The following code shows the implementation of the client function for the function chaining pattern.

Code Listing 16: Function chaining client

[FunctionName("OrderManager_Client")] public async Task<HttpResponseMessage> Client( [HttpTrigger(AuthorizationLevel.Function, "post", Route = "functionchaining/order")] HttpRequestMessage req, [DurableClient] IDurableOrchestrationClient starter, ILogger log) { log.LogInformation($"[CLIENT OrderManager_Client] --> Order received!"); string jsonContent = await req.Content.ReadAsStringAsync(); try { var order = JsonConvert.DeserializeObject<Order>(jsonContent); var instanceId = await starter.StartNewAsync("OrderManager_Orchestrator", order); log.LogInformation($"Order received - started orchestration with ID = '{instanceId}'."); return starter.CreateCheckStatusResponse(req, instanceId); } catch (Exception ex) { log.LogError("Error during order received operation", ex); } return new HttpResponseMessage(System.Net.HttpStatusCode.BadRequest); } |

When you make a POST call to the endpoint exposed by that client, you receive a response that looks like the following.

Code Listing 17: Function chaining client response

{ "id": "6a3f10a5108a416f87f2d4a2e90265b2", "statusQueryGetUri": "http://localhost:7071/runtime/webhooks/durabletask/instances/6a3f10a5108a416f87f2d4a2e90265b2?taskHub=ADFSHub&connection=Storage&code=E1PHYaGwuL1HB8UPa6AWWipN7FF8uAd1ZrSDF6O0W8l9I4U9ZIw9aQ==", "sendEventPostUri": "http://localhost:7071/runtime/webhooks/durabletask/instances/6a3f10a5108a416f87f2d4a2e90265b2/raiseEvent/{eventName}?taskHub=ADFSHub&connection=Storage&code=E1PHYaGwuL1HB8UPa6AWWipN7FF8uAd1ZrSDF6O0W8l9I4U9ZIw9aQ==", "terminatePostUri": "http://localhost:7071/runtime/webhooks/durabletask/instances/6a3f10a5108a416f87f2d4a2e90265b2/terminate?reason={text}&taskHub=ADFSHub&connection=Storage&code=E1PHYaGwuL1HB8UPa6AWWipN7FF8uAd1ZrSDF6O0W8l9I4U9ZIw9aQ==", "purgeHistoryDeleteUri": "http://localhost:7071/runtime/webhooks/durabletask/instances/6a3f10a5108a416f87f2d4a2e90265b2?taskHub=ADFSHub&connection=Storage&code=E1PHYaGwuL1HB8UPa6AWWipN7FF8uAd1ZrSDF6O0W8l9I4U9ZIw9aQ==", "restartPostUri": "http://localhost:7071/runtime/webhooks/durabletask/instances/6a3f10a5108a416f87f2d4a2e90265b2/restart?taskHub=ADFSHub&connection=Storage&code=E1PHYaGwuL1HB8UPa6AWWipN7FF8uAd1ZrSDF6O0W8l9I4U9ZIw9aQ==" } |

To generate that kind of response, you can use the method CreateCheckStatusResponse of the IDurableOrchestrationClient interface. The response provides you with a set of endpoints to get information for the specific orchestrator instance. Before analyzing the behavior of every single endpoint, we take a look at their composition.

As you can see, every single URL provided by the response has the following structure.

http://{function FQDN}/runtime/webhooks/durabletask/instances/{InstanceId}?

taskHub={task hub name}

&connection=Storage

&code={system Key}

The first part of each URL is the FQDN (fully qualified domain name) of our function app. For example, you can see localhost in the previous sample because you are debugging your function locally.

The last part of the URL before the query arguments is the instance ID of the orchestrator. If you use a non-existing instanceId, you receive an error code 404.

The URL also contains the task hub name we mentioned in the first chapter. Remember that the task hub is where all the information about the history and status of the instances is stored, so the platform needs to know where it can find the instance you want.

The property statusQueryGetUri is the URL you can use to retrieve the current status of the orchestrator. The query is a GET request, and the response looks like the following.

Code Listing 18: The status query response

{ "name": "OrderManager_Orchestrator", "instanceId": "6a3f10a5108a416f87f2d4a2e90265b2", "runtimeStatus": "Completed", "input": { "custName": "……", "custAddress": "……", "custEmail": "……", "cartId": "……", "date": "……", "price": ……, "fileName": null }, "customStatus": null, "output": { "order": { "PartitionKey": "……", "RowKey": "……", "orderId": "……", "custName": "……", "custAddress": "……", "custEmail": "……", "cartId": "……", "date": "……", "price": ……, "isReported": false, "fileName": null }, "fullPath": "invoices/5095b268-1a32-43a3-9938-fecce6fdbcd5.txt" }, "createdTime": "2021-06-22T07:00:16Z", "lastUpdatedTime": "2021-06-22T07:00:34Z" } |

The previous response contains:

- The name of orchestrator (property name).

- The current status of the orchestrator instance (property runtimeStatus).

- The input object (property input). In this property, you can find the object, serialized in JSON format, that you send to the orchestrator at the startup using the client.

- The output object (property output). You can find the output object in this property, serialized in JSON format. It is the object that the orchestrator returns at the end. This property must be empty if the orchestrator isn't finished yet, or if the orchestrator doesn’t have a return object.

- The created time and the last update time of the orchestrator status (properties createdTime and lastUpdatedTime).

A particular mention should be reserved for the output object. You need to remember that the orchestrator runs asynchronously compared to the client, and this means the client will complete its execution while the orchestrator has not yet completed its own. The value returned by the orchestrator, therefore, cannot be returned in the client's response. The durable function mechanism is always asynchronous.

You will notice that you receive from the platform all the information you have in the TaskHubInstances table, so you don't need to directly access that table.

The platform also gives you the ability to make a query over all the orchestrator instances you have in your solution. You can make a GET request using the following URL.

http://{function FQDN}/runtime/webhooks/durabletask/instances?

taskHub={task hub name}

&connection=Storage

&code={system Key}

&runtimeStatus={status1,status2,...}

&showInput=[true|false]

&showHistory=[true|false]

&showHistoryOutput=[true|false]

&createdTimeFrom={timestamp}

&createdTimeTo={timestamp}

&top={integer}

In this kind of query, you don't define the orchestratorId you are looking for, but you can define some filters:

- runtimeStatus: You can set one or more runtime statuses (separated by the ",") for the instances to filter the instances in your query. The allowed values are Pending, Running, Completed, ContinuedAsNew, Failed, and Terminated.

- showInput: If you set this to true, you have the input object in the response. The default is true.

- showHistory: If you set this to true, the execution history is included in the response. The default is false.

- showHistoryOutput: If you set this to true, the function outputs are included in the orchestration execution history in the response. The default is false.

- createdTimeFrom: If you specify this parameter, you filter the orchestrator instances, and you have in the return list only the instances created at or before the value you set. The value must be ISO 8601 timestamp.

- createdTimeTo: It is similar to the previous, but you filter all the instances created at or before the value you set.

- top: You can set the number of instances returned by the query. For example, if you set the value to 10, you will receive only the first 10 instances.

Later in this chapter, we will see that you can query your orchestrator instances using a few additional ways.

The terminatePostUri property of the function chaining client response gives you the URL to terminate a running orchestrator instance. It is a POST request, and if you want, you can set the reason for terminating the orchestration instance. You receive a different HTTP code as response, depending on the current state of the orchestrator. If the orchestrator is running (the status isn't "completed" yet), you receive an HTTP 202 code, while you receive HTTP 404 code if the orchestrator doesn't exist, or HTTP 410 if the orchestrator has completed or failed.

The purgeHistoryDeleteUri URL allows you to remove the history and all the related data for a specific orchestrator instance. It is an HTTP DELETE request, and its format is the following.

http://{function FQDN}/runtime/webhooks/durabletask/instances/{InstanceId}?

taskHub={task hub name}

&connection=Storage

&code={system Key}

The InstanceId query field is the ID of the instance you want to remove completely.

The platform exposes another URL you can use to remove orchestrator instances. The URL has the following schema.

http://{function FQDN}/runtime/webhooks/durabletask/instances?

taskHub={task hub name}

&connection=Storage

&code={system Key}

&runtimeStatus={status1,status2,...}

&createdTimeFrom={timestamp}

&createdTimeTo={timestamp}

It is an HTTP DELETE request, too, and the query fields you can set are similar to the fields you can use in the query request shown earlier in this chapter.

For this feature, you can receive only two HTTP codes as a response: HTTP 200 if the instance (or instances) is deleted correctly, or HTTP 404 if the instance (or instances) doesn't exist.

The restartPostUri URL allows you to restart a specific orchestration instance. It is an HTTP POST request, and its format is the following.

http://{function FQDN}/runtime/webhooks/durabletask/instances/{InstanceId}/restart?

taskHub={task hub name}

&connection=Storage

&code={system Key}

You can use the reason query field to trace the reason for rewinding the orchestration instance. If the restart request is accepted, you receive an HTTP 202, while you receive an HTTP 404 if the instance doesn't exist, or HTTP 410 if the instance is completed or terminated.

The last URL provided by the platform allows you to send an event to an orchestrator. We will see how to use the event approach in the human interaction pattern later in this chapter.

The URLs returned by the CreateCheckStatusResponse method allow you to interact with your orchestrator instances. However, it isn't a good idea to provide those URLs to your users. You will probably develop a software layer between your user and the orchestrator instances to implement security and access control. You can interact with your orchestrator instances using the IDurableOrchestrationClient interface in your client function or Azure Function Core Tools.

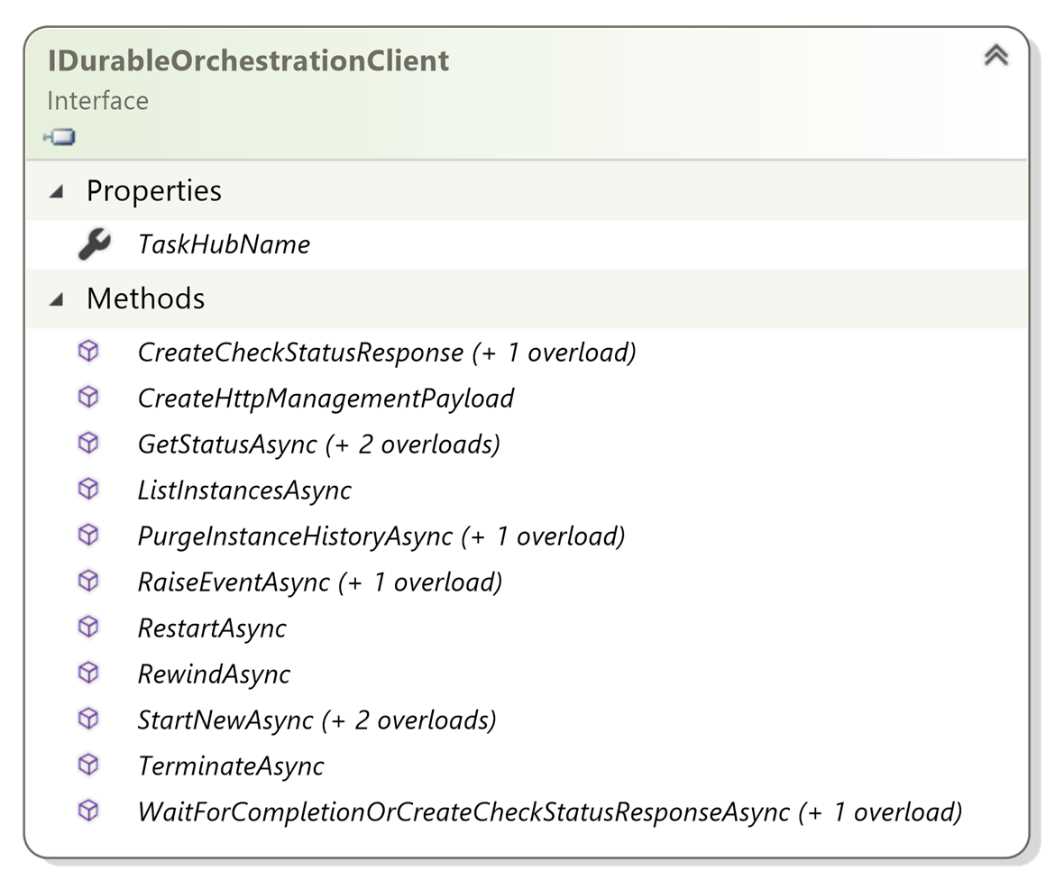

We used the IDurableOrchestrationClient interface to start a new orchestration in the previous samples, but it exposes several methods to control our orchestration instances. In the following image, you can see the IDurableOrchestrationClient interface structure.

Figure 23: The IDurableOrchestrationClient interface structure

The most important methods are:

- ListInstancesAsync: This method allows you to execute a query against your orchestration instances like you can using the statusQueryGetUri URL.

- PurgeInstanceHistoryAsync: You can use this method to remove the history of and all the data related to an instance.

- RaiseEventAsync: You can use this method to send an event to an orchestrator instance (we will see this feature in the human interaction pattern).

- RestartAsync: This method allows you to restart an orchestration.

- RewindAsync: This one is marked as obsolete: you must use RestartAsync.

- TerminateAsync: This method allows you to force the instance termination.

The WaitForCompletionOrCreateCheckStatusResponseAsync is a particular method: it waits for an amount of time you can define in one of the arguments (the default is 10 seconds) and returns a client response. If the orchestrator finishes its job during the timeout, the response contains the orchestrator output. Otherwise, it contains the same response you have using the CreateCheckStatusResponseAsync method.

Finally, you can manage your orchestration instances using Azure Functions Core Tools. You can retrieve all the options you can execute in the Azure Function Core Tools to manage the orchestration instances using the following command.

func durable

For example, if you want to retrieve the runtime status for an orchestration, you can run the command:

func durable get-runtime-status --id 20ae092dfeb444a993f23b3d511f4532

where id is the orchestration instance ID.

Note: You can find more information here about how to use the Azure Function Core Tools to manage your orchestration instances.

Monitoring

When we talk about the monitor pattern, we refer to a recurring process in a workflow in which we monitor an external service, periodically clean resources, or something similar.

You can use a standard Azure function with a timer trigger to implement a monitor pattern, but you have some limitations and difficulties using this approach. First of all, as we already saw in the previous patterns, it is not easy to orchestrate different activities invoked by the timer trigger function.

Furthermore, using a timer trigger, you cannot have flexibility on the polling interval. The interval time in a time trigger is static, and you cannot change it without redeploying your function. Using a Durable function, you can easily have different polling intervals for different instances of the same orchestrator.

An example of a monitoring pattern is exposing async HTTP APIs in a software layer and a client that periodically check the status using those APIs.

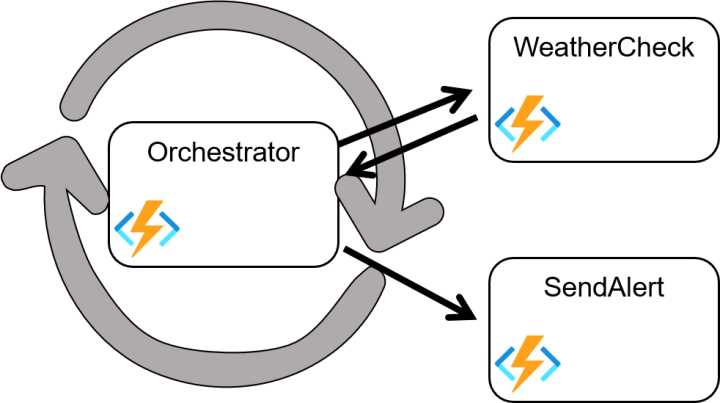

In this section, we want to analyze the monitor pattern implemented in a Durable function. Let's consider a process that monitors a city's weather conditions and sends an SMS when the weather conditions are identical to those required.

The following figure shows the pattern.

Figure 24: Monitoring pattern

As we did for the previous patterns, we need a client function to start the orchestration.

Code Listing 19: The client for monitoring pattern

[FunctionName("Monitoring_Client")] public async Task<HttpResponseMessage> Client( [HttpTrigger(AuthorizationLevel.Function, "post", Route = "monitoring/monitor")] HttpRequestMessage req, [DurableClient] IDurableOrchestrationClient starter, ILogger log) { log.LogInformation($"[CLIENT Monitoring_Client] --> Monitor started!"); string jsonContent = await req.Content.ReadAsStringAsync(); try { var monitorRequest = JsonConvert.DeserializeObject<MonitorRequest>(jsonContent); var instanceId = await starter.StartNewAsync("Monitoring_Orchestrator", monitorRequest); log.LogInformation($"Monitor started - started orchestration with ID = '{instanceId}'."); return starter.CreateCheckStatusResponse(req, instanceId); } catch (Exception ex) { log.LogError("Error during starting monitor orchestrator", ex); } return new HttpResponseMessage(System.Net.HttpStatusCode.BadRequest); } |

The client starts when it receives an HTTP POST request and tries to retrieve the MonitorRequest from the request body. The MonitorRequest has the following schema.

Code Listing 20: The MonitorRequest JSON

{ "city": "Rome,IT", "durationInMinutes": 60, "pollingInMinutes": 5, "weatherConditionCheck": "clear sky", "phoneNumber": "+39XXXXXXXXXX" } |

Using the MonitorRequest object, you can set the configuration for the specific orchestration.

The properties you can use are:

- city: The city you want to monitor (for example, Rome, IT, or New York, US-NY).

- durationInMinutes: The duration (in minutes) of the whole monitoring.

- pollingInMinutes: The time interval (in minutes) between two consecutive monitors.

- weatherConditionCheck: The desired weather condition (such as clear sky or light rain).

- phoneNumber: The phone number to use for the notification SMS.

So, for example, using the JSON shown in Code Listing 20, you can start a 60-minute monitoring workflow that checks the weather condition of Rome every five minutes and sends an SMS to the phone number set in the JSON when the weather condition becomes “clear sky.”

The orchestrator code is the following.

Code Listing 21: The monitor pattern orchestrator

[FunctionName("Monitoring_Orchestrator")] public async Task Orchestrator([OrchestrationTrigger] IDurableOrchestrationContext context, ILogger log) { log.LogInformation($"[ORCHESTRATOR Monitoring_Orchestrator] --> id : {context.InstanceId}"); var request = context.GetInput<MonitorRequest>(); DateTime endTime = context.CurrentUtcDateTime.AddMinutes(request.durationInMinutes); while (context.CurrentUtcDateTime < endTime) { bool isCondition = await context.CallActivityAsync<bool>("Monitoring_WeatherCheck", request); if (isCondition) { var notificationData = new NotificationData() { FromPhoneNumber = this.configuration.GetValue<string>("TwilioFromNumber"), PhoneNumber = request.phoneNumber, SmsMessage = $"Notification of weather {request.weatherConditionCheck} for city {request.city}" }; await context.CallActivityAsync("Monitoring_SendAlert", notificationData); break; } else { var nextCheckpoint = context.CurrentUtcDateTime.AddMinutes(request.pollingInMinutes); await context.CreateTimer(nextCheckpoint, CancellationToken.None); } } } |

The orchestrator retrieves the MonitorRequest object passed by the client and uses the duration property to calculate the end time for the monitoring. You can see that the orchestrator uses the orchestration context to calculate the end time of the monitoring—the method context.CurrentUtcDateTime.AddMinutes().

The orchestrator function must be deterministic: whenever an activity finishes its work, the orchestrator runs again from the beginning, and the state is rebuilt (using the event sourcing approach we saw in the second chapter).

If you use the standard .NET classes to calculate the end time for the monitor workflow, these classes calculate a different date each time the same orchestrator instance runs and can cause problems in reconstructing the state.

For this reason, every time you must do something that can be different every time the orchestrator runs (like a time calculation), you need to use the context or call an activity.

The main part of the orchestrator is the monitoring loop. Inside this loop, the orchestrator calls the WeatherCheck activity, tests its return value, and if needed, calls the SendAlert activity and closes the monitoring workflow.

The WeatherCheck activity code is shown in the following snippet.

Code Listing 22: The weather check activity

[FunctionName("Monitoring_WeatherCheck")] public async Task<bool> WeatherCheck([ActivityTrigger] MonitorRequest request, ILogger log) { log.LogInformation($"[ACTIVITY Monitoring_WeatherCheck] --> request : {request}"); try { var cityCondition = await this.weatherService.GetCityInfoAsync(request.city); if (cityCondition != null) return cityCondition.HasCondition(request.weatherConditionCheck); } catch (Exception ex) { log.LogError(ex, $"Error during calling weather service"); } return false; } |

The interesting thing in the previous snippet of code is that the activity uses a class (contained in the weatherService field) to interact with the external service that gives it the weather condition. It is an alternative example of how you can interact with an external service. You can create your custom binding to interact with an external service, but you can also leverage the dependency injection approach to inject the actual classes into a function.

If you look at the class that contains all the functions related to the monitoring pattern, you can find its constructor.

Code Listing 23: The function class constructor

private readonly IWeatherService weatherService; private readonly IConfiguration configuration; public MonitoringFunctions(IWeatherService weatherService, IConfiguration configuration) { this.configuration = configuration ?? throw new ArgumentNullException(nameof(configuration)); this.weatherService = weatherService ?? throw new ArgumentNullException(nameof(weatherService)); this.configuration = configuration; this.weatherService.ApiKey = configuration.GetValue<string>("WeatherServiceAPI"); } |

Azure Functions can use the dependency injection provided by the ASP.NET Core platform. You can define a startup class in your Azure Functions project like the following.

Code Listing 24: The function class construtor

[assembly: WebJobsStartup(typeof(Startup))] public class Startup : IWebJobsStartup { public void Configure(IWebJobsBuilder builder) { builder.Services.AddTransient<IWeatherService, OpenWeatherMapService>();

builder.Services.BuildServiceProvider(); } } |

The assembly attribute tells the platform to run the Startup class when the functions host starts.

In the Configure method, we can define the resolution for all our classes. For example, in the previous snippet of code, we use the AddTransient method to configure the dependency resolver to resolve the IWeatherService interface with the OpenWeatherMapService class every time a constructor has a dependency with that interface.

Note: You can find more information here about how you can use dependency injection in Azure Functions.

The following snippet of code shows the SendAlert activity.

Code Listing 25: The SendAlert activity

[FunctionName("Monitoring_SendAlert")] [return: TwilioSms(AccountSidSetting = "TwilioAccountSid", AuthTokenSetting = "TwilioAuthToken")] public CreateMessageOptions SendAlert([ActivityTrigger] NotificationData notificationData, ILogger log) { log.LogInformation($"[ACTIVITY Monitoring_SendAlert] --> notificationData : {notificationData}"); var message = new CreateMessageOptions(new PhoneNumber(notificationData.PhoneNumber)) { From = new PhoneNumber(notificationData.FromPhoneNumber), Body = notificationData.SmsMessage }; return message; } |

This activity uses the Twilio binding to send SMSs. It is a return binding, which means you create the message you want to send and return it from the function. After the function is completed without error, the binding implementation sends the message using the account configured in the attribute.

Human interaction

In some common scenarios, you have the main workflow that an external interaction can influence.

For example, you can imagine an approval process:

- Someone requests approval for something (such as a holiday vacation).

- The approval request waits for an amount of time before it is automatically approved.

- During this period, someone can approve or reject the vacation request.

In that scenario, you need to interact with your workflow from the external. You need to send one or more events to the workflow to change its status (for example, the vacation rejection).

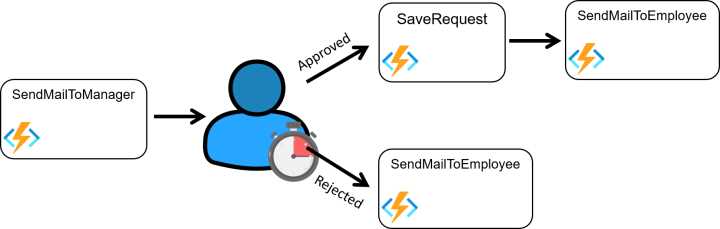

In the following figure, you can see the workflow mentioned before.

Figure 25: Human interaction pattern

What potential issues might we have when implementing this pattern using a standard Azure function?

The first problem appears when you try to implement your function that waits for a while before automatically approving the request. Unfortunately, a standard Azure function cannot run for a long time at will, so we can't start a function and wait.

The second problem you may have if you implement human interaction with an Azure function is how to interact with it if, for example, the manager approves the vacation request.

When an Azure function is running, it is not easy to communicate with it. You could, for example, use a queue and implement your function to check that queue periodically, but your code becomes complex and challenging to maintain.

Using the Durable Functions platform, you can leverage the durable context (through the IDurableOchestrationContext) that gives you several methods to create timers and interact with a running orchestrator.

We need a client to start the workflow: the employee will request his vacation using the REST API exposed by the following client function.

Code Listing 26: The human interaction pattern client

[FunctionName("HumanInteraction_Client")] public async Task<HttpResponseMessage> Client( [HttpTrigger(AuthorizationLevel.Function, "post", Route = "humaninteraction/vacationrequest")] HttpRequestMessage req, [DurableClient] IDurableOrchestrationClient starter, ILogger log) { log.LogInformation($"[CLIENT HumanInteraction_Client] --> Vacation requested!"); string jsonContent = await req.Content.ReadAsStringAsync(); try { var vacationRequest = JsonConvert.DeserializeObject<VacationRequest>(jsonContent); if (vacationRequest.IsValid()) { var instanceId = await starter.StartNewAsync("HumanInteraction_Orchestrator", vacationRequest); log.LogInformation($"Monitor started - started orchestration with ID = '{instanceId}'."); return starter.CreateCheckStatusResponse(req, instanceId); } } catch (Exception ex) { log.LogError("Error during requesting vacation", ex); } return new HttpResponseMessage(System.Net.HttpStatusCode.BadRequest); } |

The client is similar to the other clients you saw previously in this chapter. It is started by an HTTP POST request and retrieves the vacation request from the body.

The JSON of the vacation request looks like the following.

Code Listing 27: The vacation request JSON

{ "employeeID": "11111", "employeeFirstName": "Massimo", "employeeLastName": "Bonanni", "employeeEmail": "*****@****.***", "managerEmail": "*****@****.***", "dateFrom": "12/24/2021", "dateTo": "12/26/2021", "notes": "I need a vacation!!" } |

The request contains:

- employeeID: The identification of the employee.

- employeeFirstName, employeeLastName: The first name and last name of the employee.

- employeeEmail: The employee email. The workflow uses this email to send an email to the employee to communicate the result of the approval process.

- managerEmail: The email of the employee’s manager. The workflow uses this email to notify the manager when the employee requests a vacation.

- dateFrom, dateTo: The range of dates of the vacation.

- notes: The comments related to the request.

The vacation request is elementary because this is just an example, but you can easily understand that the JSON may be more complex.

The orchestrator started by the client is the following.

Code Listing 28: The human interaction orchestrator

[FunctionName("HumanInteraction_Orchestrator")] public async Task Orchestrator([OrchestrationTrigger] IDurableOrchestrationContext context, ILogger log) { log.LogInformation($"[ORCHESTRATOR HumanInteraction_Orchestrator] --> id : {context.InstanceId}"); var request = context.GetInput<VacationRequest>(); var response = new VacationResponse() { request = request, instanceId = context.InstanceId }; await context.CallActivityAsync("HumanInteraction_SendMailToManager", response); using (var timeoutCts = new CancellationTokenSource()) { DateTime expiration = context.CurrentUtcDateTime.AddDays(1); Task timeoutTask = context.CreateTimer(expiration, timeoutCts.Token); Task approvedResponseTask = context.WaitForExternalEvent(RequestEvents.Approved); Task rejectedResponseTask = context.WaitForExternalEvent(RequestEvents.Rejected); var taskCompleted = await Task.WhenAny(timeoutTask, approvedResponseTask, rejectedResponseTask); if (taskCompleted == approvedResponseTask || taskCompleted == timeoutTask) // request approved { if (taskCompleted == approvedResponseTask) timeoutCts.Cancel(); response.isApproved = true; await context.CallActivityAsync("HumanInteraction_SaveRequest", response); } else { timeoutCts.Cancel(); response.isApproved = false; } await context.CallActivityAsync("HumanInteraction_SendMailToEmployee", response); } } |

The orchestrator calls the SendMailToManager activity to send the notification email to the employee’s manager.

Code Listing 29: The send email to manager activity

[FunctionName("HumanInteraction_SendMailToManager")] public async Task SendMailToManager([ActivityTrigger] VacationResponse response, [SendGrid(ApiKey = "SendGridApiKey")] IAsyncCollector<SendGridMessage> messageCollector, ILogger log) { log.LogInformation($"[ACTIVITY HumanInteraction_SendMailToManager] --> response : {response}"); var message = SendGridHelper.CreateMessageForManager(response); await messageCollector.AddAsync(message); } |

After sending the email to the employee's manager, the orchestrator creates three tasks to manage the waiting time and the two interactions from outside (approval or rejection by the manager).

In particular:

- It uses the CreateTimer method of the context class to create a durable timer. A durable timer is a feature provided by the platform that allows you to restart the orchestrator after an interval of time. The platform completely manages it: your orchestrator will stop, and when the timer elapses, the platform will recall it.

- It uses the WaitForExternalEvent method of the context class to have your orchestrator listen for external events. The orchestrator will run again when an accept or reject event is sent. In the previous code, you have two different tasks, one for each type of event. You can define and manage the number of events you want.

In this case, the orchestrator uses the method WhenAny of the Task class to continue in the workflow when one of the tasks (the timer or one of the event listeners) finishes its job. The timer task will finish its job when the time is over, while the event listener tasks finish their jobs when one of the events is sent to the orchestrator.

Exiting from the WhenAny method, the variable taskCompleted contains the task that completes its job, and we can check it to proceed with the flow. In our sample, if the task completed is the event listener task for the event "accepted" or the timer, we call the SaveRequest activity to persist the vacation request in the enterprise repository (in our case, it is a storage table).

In the end, whether the request was accepted or rejected, we send the email to the employee using the SendMailToEmployee activity to notify him of the result of the process.

Another detail to consider is the way the timer is handled. We previously said that the platform actually manages the timer (it is a durable timer), and therefore, when an event arrives (be it accepted or rejected), we must signal to the platform that we don’t need the timer, and the platform must cancel it.

When we need to cancel the timer (for example, one of the two expected events has arrived), we must execute the Cancel method.

With Durable Functions, an event is a sort of notification coming from outside your orchestrator composed of a string that defines its name and a possible payload that contains the event data.

You have two different events, called approved and rejected in the previous example, and they don’t have data associated.

But how I can send an event to an orchestrator?

You can accomplish that task is several ways. You can use one of the HTTP endpoints provided by the platform to manage the orchestrations we saw in the HTTP APIs paragraph.

In particular, if you look at the JSON in Code Listing 17, you can see the property sendEventPostUri. This property contains a REST POST endpoint you can use to send an event to a specific orchestrator instance.

The signature of the URL is the following.

http://{function FQDN}/runtime/webhooks/durabletask/instances/{instanceId}/raiseEvent/{eventName}?

taskHub={task hub name}

&connection=Storage

&code={system Key}

In the previous URL, you address the orchestrator instance using the instanceId and the event using the eventName in the URL signature.

The request is a POST, and its body contains the event payload (if you need it). You receive a response that contains an HTTP 202 code if the event was accepted for processing, an HTTP 400 if the request contains an invalid JSON, an HTTP 404 if the orchestrator doesn’t exist, or an HTTP 410 if the instance is completed and cannot process the event.

You can also use the Azure Function Core Tools to send an event to your orchestrations. The following command shows you how you can send the approve event to the orchestrator.

func durable raise-event --id 0ab8c55a66644d68a3a8b220b12d209c --event-name approve--event-data @eventdata.json

The eventdata.json file contains the payload of our event.

Finally, the third way you can send an event to your orchestrator is by implementing a client function. Inside that function, you can use the RaiseEventAsync method of the IDurableOrchestrationClient interface (see Figure 23 for more info).

The following snippet of code shows you how the client approves the vacation request.

Code Listing 30: The approve vacation client function

[FunctionName("HumanInteraction_ClientApprove")] public async Task<HttpResponseMessage> ClientApprove( [HttpTrigger(AuthorizationLevel.Function, "put", Route = "humaninteraction/vacationrequest/{instanceId}/approve")] HttpRequestMessage req string instanceId, [DurableClient] IDurableOrchestrationClient starter, ILogger log) { log.LogInformation($"[CLIENT HumanInteraction_ClientApprove] --> instanceId {instanceId} approved"); await starter.RaiseEventAsync(instanceId, RequestEvents.Approved, null); return new HttpResponseMessage(System.Net.HttpStatusCode.OK); } |

It is an HTTP triggered function that responds to an HTTP PUT.

In this example, we do not need data inside the request body because the URL signature contains the instance ID, and the function only handles the approve event.

If necessary, the request's body can contain all the data (a serialized object in JSON format) to support the event. This data can be passed to the orchestrator.

The client sends the event to the orchestrator using the RaiseEventAsync method. This method has three arguments: the instance ID, the event name (a string), and the object you want to pass to the orchestrator.

In the same way, we implement the client to send the “rejected” event.

Code Listing 31: The reject vacation client function

[FunctionName("HumanInteraction_ClientReject")] public async Task<HttpResponseMessage> ClientReject( [HttpTrigger(AuthorizationLevel.Function, "put", Route = "humaninteraction/vacationrequest/{instanceId}/reject")] HttpRequestMessage req, string instanceId, [DurableClient] IDurableOrchestrationClient starter, ILogger log) { log.LogInformation($"[CLIENT HumanInteraction_ClientReject] --> instanceId {instanceId} rejected"); await starter.RaiseEventAsync(instanceId, RequestEvents.Rejected, null); return new HttpResponseMessage(System.Net.HttpStatusCode.OK); } |

One of the most common questions is: what is the best approach for managing one or more events? Must we use the HTTP APIs provided by the platform or implement our clients?

You use the HTTP APIs when you don't want (or don't need) to verify the event payload while you implement your custom client when you want to verify event payload or add some logic before sending the event to the orchestrator.

Implementing a custom client allows you to have more control over the complete end-to-end process.

In the following snippet of code, you can find the implementation of the activities used by the orchestrator to send emails to the employee and the manager and save the request in the database.

Code Listing 32: The activities of the human interaction pattern

[FunctionName("HumanInteraction_SendMailToManager")] public async Task SendMailToManager([ActivityTrigger] VacationResponse response, [SendGrid(ApiKey = "SendGridApiKey")] IAsyncCollector<SendGridMessage> messageCollector, ILogger log) { log.LogInformation($"[ACTIVITY HumanInteraction_SendMailToManager] --> response : {response}"); var message = SendGridHelper.CreateMessageForManager(response); await messageCollector.AddAsync(message); } [FunctionName("HumanInteraction_SendMailToEmployee")] public async Task SendMailToEmployee([ActivityTrigger] VacationResponse response, [SendGrid(ApiKey = "SendGridApiKey")] IAsyncCollector<SendGridMessage> messageCollector, ILogger log) { log.LogInformation($"[ACTIVITY HumanInteraction_SendMailToEmployee] --> response : {response}"); var message = SendGridHelper.CreateMessageForEmployee(response); await messageCollector.AddAsync(message); } [FunctionName("HumanInteraction_SaveRequest")] public async Task<bool> SaveRequest([ActivityTrigger] VacationResponse response, [Table("vacationsTable", Connection = "StorageAccount")] IAsyncCollector<VacationResponseRow> vacationsTable, ILogger log) { log.LogInformation($"[ACTIVITY HumanInteraction_SaveRequest] --> response : {response}"); var vacationRow = new VacationResponseRow(response); await vacationsTable.AddAsync(vacationRow); return true; } |

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.