CHAPTER 2

Durable Functions Fundamentals

Durable Functions components

Azure Functions is a great technology to implement using your favorite programming language, a unit of software. You can debug and test the functions easily, but they have a few limitations.

First, you cannot call a function directly from another function. Of course, you can make an HTTP call or use a queue, but you cannot call the other function directly, and this limitation makes your solution more complex.

The second (and more critical) limitation is that you cannot create a stateful function, which means you cannot store data in the function. Of course, you can use external services like storage or CosmosDB to store your data, but you have to implement the persistence layer in your function, and again, this situation makes your solution more complex.

For example, if you want to create a workflow using Azure Functions, you have to store the workflow status and interact with other functions.

A workflow is a set of stages, and each of them is typically a function call. You have to store the stage you reach and call other functions directly. You can implement a workflow using Azure Functions, but you need to find a solution to store (using an external service and some bindings) the workflow status and call the functions that compose your workflow.

Durable Functions is an Azure Functions extension that implements triggers and bindings that abstract and manage state persistence. Using Durable Functions, you can easily create stateful objects entirely managed by the extension.

You can implement Durable Functions using C#, F#, JavaScript, Python, and PowerShell.

Note: If you implement your Durable Functions using C#, you need to reference the package Microsoft.Azure.WebJobs.Extensions.DurableTask.

Clients, orchestrators, and activities

In the following figure, you can see the main components in a Durable function.

Figure 15: Durable Functions components

All the components in the Durable Functions world are Azure functions, but they use specific triggers and bindings provided by the extension.

Every component has its responsibility:

- Client: The client starts or sends commands to an orchestrator. It is an Azure function triggered by a built-in (or custom) trigger as a standard Azure function. It uses a custom binding (DurableClient, provided by the Durable Functions extension) to interact with the orchestrator.

- Orchestrator: The orchestrator implements your workflow. Using code, it describes what actions you want to execute and the order of them. An orchestrator is triggered by a particular trigger provided by the extension (OrchestrationTrigger). The OrchestrationTrigger gives you a context of execution you must use to call activities or other orchestrators. The purpose of the orchestrator is only to orchestrate activities or other orchestrators (sub-orchestration). It doesn’t have to perform any calculation or I/O operations, but only governs activities’ flow.

- Activity: The basic unit of work of your workflow, the activity is an Azure function triggered by an orchestrator using the ActivityTrigger provided by the extension. The activity trigger gives you the capability to receive data from the orchestrator. Inside the activity, you can use all the bindings you need to interact with external systems.

You have another type of function in the Durable Functions platform called the entity, but we will see it in another chapter later in this book.

The triggers and bindings provided by the extension abstract the state persistence.

How Durable functions manage state: function chaining

The Durable Functions extension is based on the Durable Task Framework. The Durable Task Framework is an open-source library provided by Microsoft that helps you implement long-running orchestration tasks. It abstracts the workflow state persistence and manages the orchestration restart and replay.

Note: The Durable Task Framework is available on GitHub.

The Durable Task Framework uses Azure Storage as the default persistence store for the workflow state, but you can use different stores using extended modules. At the moment, you can use Service Bus, SQL Server, or Netherite. To configure a different persistence store, you need to change the host.json file.

Note: Netherite is a workflow execution engine based on Azure EventHub and FASTER (a high-performance key-value store), implemented by Microsoft Research.

We will refer to the default persistence layer (Azure Storage) during the paragraph's continuation, but what we will say is almost the same for any other persistence layer.

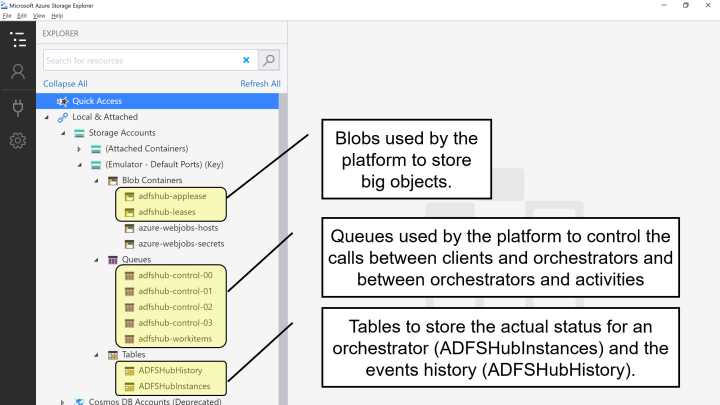

Durable functions use queues, tables, and blobs inside the storage account you configure in your function app settings for the following purposes:

- Queues: The persistence layer uses the queue to schedule orchestrators and activities’ executions. For example, every time the platform needs to invoke an activity from an orchestrator, it creates a specific message in one of the queues. The ActivityTrigger reacts to that message and starts the right activity.

- Tables: Durable functions use storage tables to store the status of each orchestrator (instances table) and all their execution events (history table). Every time an orchestrator does something (such as call an activity or receive a result from an activity), the platform writes one or more events in the history table. This event sourcing approach allows the platform to reconstruct the actual status of each orchestrator during every restart.

- Blobs: Durable functions use the blobs when the platform needs to save data with a size greater than the limitations of queues and tables (regarding the maximum size of a single entity or a single message).

The Durable Functions platform uses JSON as standard, but you can customize the serialization by implementing your custom serialization component.

Queues, tables, and blobs are grouped in a logical container called the task hub. You can configure the name of the task hub for each function app by modifying the host.json file. The following file is an example.

Code Listing 4: Setting the name of the task hub in the host.json file

{ "version": "2.0", "extensions": { "durableTask": { "hubName": "ADFSHub" } } } |

Using the previous host.json file, the Durable Functions platform will create the queues, table, and blobs shown in the following figure.

Figure 16: Queues, tables, and blobs in a task hub

As you can see, the name you configure in the hubName property of the host.json file becomes the prefix of all the queues, tables, and blobs used by the platform.

To better explain the mechanism used by Durable Functions to store the progress of an orchestrator, let's consider a simple example of a workflow called function chaining.

In the following figure, you can see a simple function chaining.

Figure 17: Function chaining

In this diagram, we suppose a simple workflow that manages a customer order. A client function receives an HTTP request that contains the order. The client starts an orchestrator, and the orchestrator calls the following activities:

- SaveOrder: Receives the order from the orchestrator and saves it in table storage (the orders table).

- CreateInvoice: Creates an invoice file in blob storage.

- SendMail: Sends an email to the customer for order confirmation.

Before looking at the code for the client, the orchestrator, and the activities, you must notice that a pattern like this can be implemented using standard Azure Functions and storage queues.

Each function could call the next one in the sequence using a queue, but you must manage two different queues, and if the number of activities grows, the number of queues becomes too high. Furthermore, the relationship between each function and its queue becomes an implementation detail, and you must document it very well.

Finally, your solution can become very complex to manage if you have to introduce compensation mechanisms in case of errors. Imagine you want to call a different function if the CreateInvoice activity throws an exception. How can you do this? Of course, you can introduce different queues for each exception you want to manage, but you understand that the complexity of your implementation just became unmanageable.

Note: You can find all the code used in this book at https://github.com/massimobonanni/AzureDurableFunctionsSuccinctly.

Now we can take a look at the code starting from the client.

Code Listing 5: Function chaining client

[FunctionName("OrderManager_Client")] public async Task<HttpResponseMessage> Client( [HttpTrigger(AuthorizationLevel.Function, "post", Route = "functionchaining/order")] HttpRequestMessage req, [DurableClient] IDurableOrchestrationClient starter, ILogger log) { log.LogInformation($"[CLIENT OrderManager_Client] --> Order received!"); string jsonContent = await req.Content.ReadAsStringAsync(); try { var order = JsonConvert.DeserializeObject<Order>(jsonContent); var instanceId = await starter.StartNewAsync("OrderManager_Orchestrator", order); log.LogInformation($"Order received - started orchestration with ID = '{instanceId}'."); return starter.CreateCheckStatusResponse(req, instanceId); } catch (Exception ex) { log.LogError("Error during order received operation", ex); } return new HttpResponseMessage(System.Net.HttpStatusCode.BadRequest); } |

The client is an Azure function with an HTTP trigger and uses the DurableClient attribute to declare the binding that allows you to manage the orchestrator.

The IDurableOrchestrationClient instance provided by the Durable Functions platform is the payload class for the new binding. StartNewAsync allows you to start a new orchestration, giving the name of the orchestration function and a custom object (in our sample, the order deserialized from the request) and returns the instance ID of the orchestrator.

Every time you start a new orchestrator, the platform creates a new instance and provides you with an ID that allows you to manage and control the specific orchestration.

The client function finishes returning a response generated by the method CreateCheckStatusResponse. We will talk about the content of this response in the paragraph related to the async HTTP APIs pattern.

Code Listing 6: Function chaining orchestrator

[FunctionName("OrderManager_Orchestrator")] public async Task<Invoice> Orchestrator( [OrchestrationTrigger] IDurableOrchestrationContext context, ILogger log) { log.LogInformation($"[ORCHESTRATOR OrderManager_Orchestrator] --> id : {context.InstanceId}"); var order = context.GetInput<Order>(); var orderRow = await context.CallActivityAsync<OrderRow>("OrderManager_SaveOrder", order); var invoice = await context.CallActivityAsync<Invoice>("OrderManager_CreateInvoice", orderRow); await context.CallActivityAsync("OrderManager_SendMail", invoice); return invoice; } |

The previous code contains the implementation for the orchestrator for our function chaining pattern.

The OrchestrationTrigger trigger starts the function and manages the restart every time an activity, called by the orchestrator, finishes. You can also use the trigger to retrieve the object passed by the client (using the GetInput method).

The orchestrator must implement only the workflow flow, and must not implement calculation, I/O operation, or similar. The code you write in an orchestrator must be deterministic. This means you cannot use values generated inside the orchestrator (like a random value), or values can change every time the orchestrator runs (for example, a value related to local time). Remember that the platform restarts the orchestrator every time an activity finishes and rebuilds its state using the events stored in the history table mentioned before. The state-building phase must be deterministic; otherwise, you receive an error.

If you need a random value, for example, you can create an activity to generate it and call the activity from the orchestrator.

As you can see in the previous code, you can call an activity (using the method CallActivityAsync), passing an object, and retrieve the result. The objects you involved in the process are custom objects (so you can create the classes you need to pass the data you need), and the only limitation is that those classes must be JSON serializable.

Now complete the code showing the three activities.

Code Listing 7: Function chaining save order activity

[FunctionName("OrderManager_SaveOrder")] public async Task<OrderRow> SaveOrder([ActivityTrigger] Order order, [Table("ordersTable", Connection = "StorageAccount")] IAsyncCollector<OrderRow> ordersTable, ILogger log) { log.LogInformation($"[ACTIVITY OrderManager_SaveOrder] --> order : {order}"); var orderRow = new OrderRow(order); await ordersTable.AddAsync(orderRow); return orderRow; } |

The SaveOrder activity is an Azure function triggered by an ActivityTrigger. The ActivityTrigger, like the OrchestrationTrigger, uses the queues mentioned earlier to schedule the execution of the function when an orchestrator requests it using the CallActivityAsync method.

This method creates a message containing all the information the platform needs to start the activity and puts it in the TaskHub-workitems queue, as shown in Figure 16. The ActivityTrigger is listening to that queue and can start the activity. The following JSON shows an example of a message created by the orchestrator.

Code Listing 8: An example of a message generated by the orchestrator

{ "$type": "DurableTask.AzureStorage.MessageData", "ActivityId": "3a718fb6-80fc-4a90-ba92-6366da789f1d", "TaskMessage": { "$type": "DurableTask.Core.TaskMessage", "Event": { "$type": "DurableTask.Core.History.TaskScheduledEvent", "EventType": 4, "Name": "OrderManager_SaveOrder", "Version": "", "Input": "[{\"$type\":\"DurableFunctions.FunctionChaining.Order, DurableFunctions\",\"custName\":\"Massimo Bonanni\",\"custAddress\":\"Viale Giuseppe Verdi 1, Roma\",\"custEmail\":\"[email protected]\",\"cartId\":\"11111111\",\"date\":\"2021-05-18T13:00:00\",\"price\":435.0,\"fileName\":null}]", "EventId": 0, "IsPlayed": false, "Timestamp": "2021-06-07T14:26:30.4134592Z" }, "SequenceNumber": 0, "OrchestrationInstance": { "$type": "DurableTask.Core.OrchestrationInstance", "InstanceId": "de534343c593443ca45dbc6165eb44ce", "ExecutionId": "b064f9960f0447e983547c8d0801d5b6" } }, "CompressedBlobName": null, "SequenceNumber": 2, "Episode": 1, "Sender": { "InstanceId": "de534343c593443ca45dbc6165eb44ce", "ExecutionId": "b064f9960f0447e983547c8d0801d5b6" }, "SerializableTraceContext": null } |

The message contains all the information the platform needs to start the right activity:

- Input: The object (serialized) passed from the orchestrator to the activity.

- Name: The name of the activity to call.

- OrchestrationInstance: The orchestration information in terms of InstanceId and ExecutionId.

In the following snippets of code, you can see the implementation of the other two activities involved in the workflow.

Code Listing 9: Function chaining create invoice activity

[FunctionName("OrderManager_CreateInvoice")] [StorageAccount("StorageAccount")] public async Task<Invoice> CreateInvoice([ActivityTrigger] OrderRow order, IBinder outputBinder, ILogger log) { log.LogInformation($"[ACTIVITY OrderManager_CreateInvoice] --> order : {order.orderId}"); var fileName = $"invoices/{order.orderId}.txt"; using (var outputBlob = outputBinder.Bind<TextWriter>(new BlobAttribute(fileName))) { await outputBlob.WriteInvoiceAsync(order); } var invoice = new Invoice() { order = order, fullPath = fileName }; return invoice; } |

The CreateInvoice activity receives the order written in the storage table by the SaveOrder activity and creates the order invoice in a blob storage container.

Code Listing 10: Function chaining send mail activity

[FunctionName("OrderManager_SendMail")] [StorageAccount("StorageAccount")] public async Task SendMail([ActivityTrigger] Invoice invoice, [SendGrid(ApiKey = "SendGridApiKey")] IAsyncCollector<SendGridMessage> messageCollector, IBinder invoiceBinder, ILogger log) { log.LogInformation($"[ACTIVITY OrderManager_SendMail] --> invoice : {invoice}"); SendGridMessage message; using (var inputBlob = invoiceBinder.Bind<TextReader>(new BlobAttribute(invoice.fileName))) { message = await SendGridHelper.CreateMessageAsync(invoice, inputBlob); } await messageCollector.AddAsync(message); } |

Finally, the SendMail activity receives the invoice data from the orchestrator and sends an email to the customer using the SendGrid binding provided by Microsoft.

Note: SendGrid is an email delivery service that allows you to automate the email sending process using REST APIs. Microsoft provides a set of bindings to interact with SendGrid, and you can find them in the package Microsoft.Azure.WebJobs.Extensions.SendGrid. You can find more information on how you can use SendGrid in your Azure functions here.

Orchestrator event-sourcing pattern

We previously discussed function chaining, one of the simplest workflow patterns we can implement using Durable Functions. The question is: how does the platform execute every single instance of the orchestrator, reconstructing precisely the state it had reached?

Durable functions are Azure functions, and therefore, cannot have a long execution time. The Durable Functions platform runs the orchestrator for the time necessary to perform the steps required to invoke one of the activities. It stops (literally) and restarts when the activity completes its job. At that point, the platform must reconstruct the state the orchestrator had reached to resume the execution with the remaining activities.

The platform manages the state of every single orchestrator using the event-sourcing pattern. Every time the orchestrator needs to start an activity, the platform stops its execution and writes a set of rows in a storage table. Each row contains what the orchestrator does before starting the activity (events sourcing).

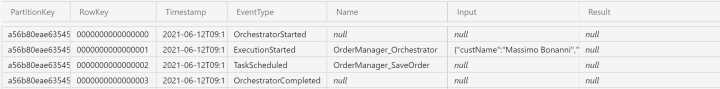

As an example, let's imagine we are running the orchestrator shown in Code Listing 6. The platform executes the instructions until the orchestrator calls the SaveOrder activity. The platform writes the startup message of the activity in the queue (as we saw previously), stops the execution of the orchestrator, and writes a few rows in the TaskHubHistory table to store the progress of the workflow.

In the next figure, you can see an example of what the platform writes in the table.

Figure 18: Orchestrator history before calling SaveOrder activity

This table shows only a subset of all the columns used in the history table. We analyze only the columns helpful to understand the event-sourcing pattern.

The meaning of each column is the following:

- PartitionKey: The platform uses the orchestrator instance ID to partition events (and therefore, the state). The events of each instance of the orchestrator will always be in the same partition.

- RowKey: The platform uses the order of succession of events as a row key.

- TimeStamp: This is the time in which the event occurred.

- EventType: This is the event type. For example, the first event is always OrchestratorStarted. The event type TaskScheduled is used to signal that the orchestrator starts an activity.

- Name: If the field is used, it contains the name of the functions object of the event. For example, if you look at RowKey 1, you can notice that the name field contains the value OrderManager_Orchestrator, which is exactly the name of the orchestrator function. In the case of an activity, we will find the name of the activity (look at RowKey 2).

- Input: This field contains the serialization of all the input objects passed to the orchestrator. In RowKey 1, you can see the payload received by the orchestrator from the client function.

- Result: This contains the serialization of the objects returned by the single activity when they finish their job.

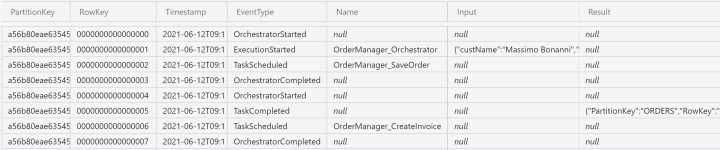

When the SaveOrder activity finishes its job, the platform writes a new message in the communication queue to start the orchestrator again. The OrchestrationTrigger captures that message and starts the orchestrator function (the message contains the ID of the instance of the orchestrator, so the platform can start the correct orchestrator instance).

The platform reads the rows in the history table and reconstructs the workflow state. It knows that the orchestrator already called the SaveOrder activity, and it must proceed with the instructions after the CallActivityAsync method.

Again, the platform creates a message in the communication queue to call the CreateInvoice function, stops the orchestrator, and writes some rows in the history table.

The new situation for the history table is shown in the following figure.

Figure 19: Orchestrator history before calling the CreateInvoice activity

You can see the serialization of the return object provided by the save order activity in the result field of RowKey 0005.

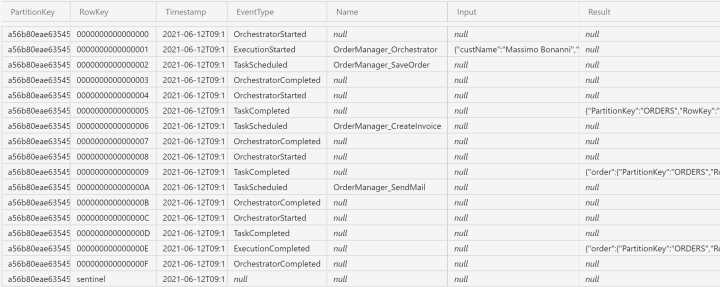

The platform iterates the pattern until the orchestrator finishes its execution. Every time the orchestrator restarts because an activity finishes its job, the platform reconstructs the state using the history table.

You can see all the history rows written by the platform for a function chaining orchestrator in the following figure.

Figure 20: Full execution history for the function chaining orchestrator

Another helpful table used by the platform is the TaskHubInstances table. The platform creates one row for each orchestrator instance in this table, and each row contains the current status of the orchestrator.

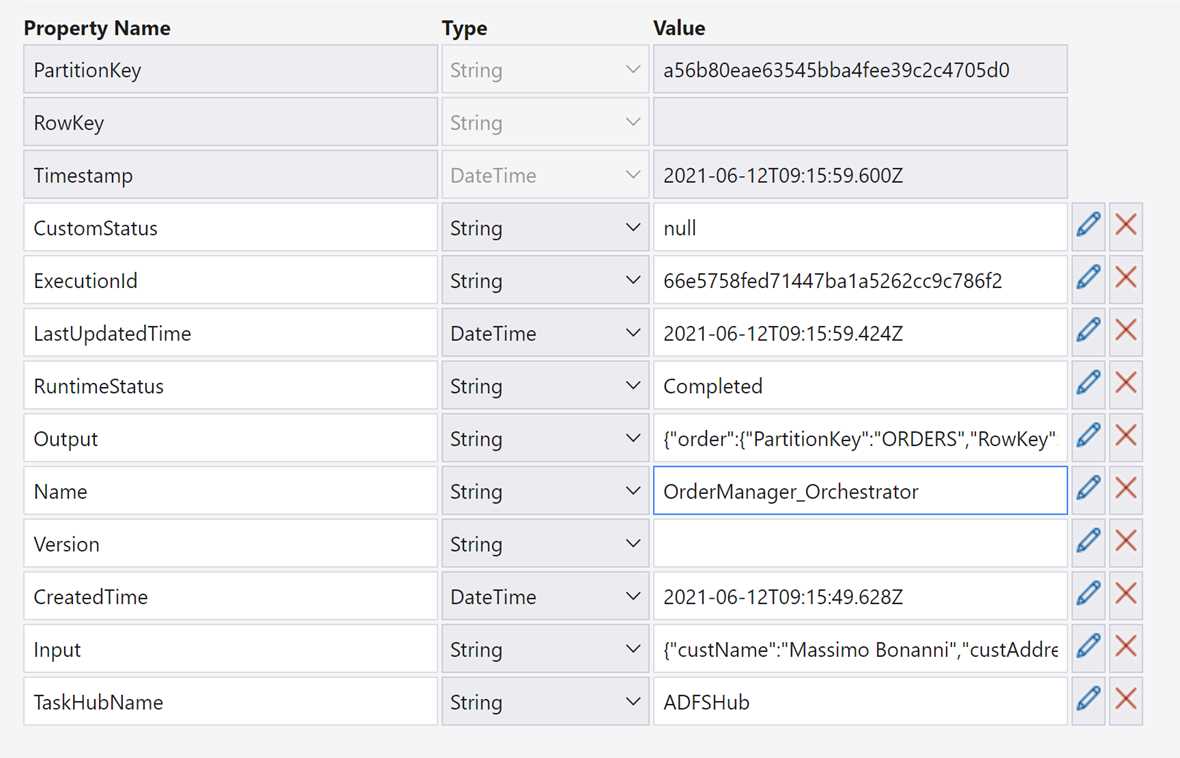

In the following figure, you can see the instance row for the previous orchestrator execution.

Figure 21: The actual state of an orchestrator in the instances table

As you can see in the table in Figure 21, the platform saves all the information you can use to understand the current state of each orchestrator. The most interesting fields are:

- LastUpdatedTime: This is the timestamp of the last update.

- RuntimeStatus: This field contains the current status of the orchestrator and allows you to understand if the orchestrator finishes its job.

- Output: In this field, you can find the return object of the orchestrator (if the orchestrator returns an object). The returned object is serialized.

- Input: Here, you can find the input object passed to the orchestrator. Also, in this case, the object is serialized.

Versioning issues

The event sourcing approach allows the platform to understand the step the orchestrator reached in the previous execution and reconstruct the state. But what happens if we change code in the orchestrator (or in one of the activities used by it)?

Of course, there aren't issues with the new executions: they run using the new code. You can have problems with the orchestrator in the running state (the orchestrator instances that have started their job but not finished it yet). After code changes, in fact, at the next execution, the platform tries to reconstruct the orchestrator status—but the code in the orchestrator could be different from the one that generated the set of events stored in the history table. In that scenario, the orchestrator instance throws an exception.

You need to take care of those breaking changes. Two of the most common are:

- Change orchestrator or activity signature: This breaking change occurs when you modify the number or types of the arguments of an orchestrator or activity.

- Change the orchestration logic: In this breaking change, you change the code inside an orchestrator function, and the new one is different from the previous in terms of workflow.

There are some strategies to manage those breaking changes:

- Do nothing: Using this approach, you continue to receive errors from the orchestrators (because the platform tries to run the orchestrator every time an exception is generated). It isn't the recommended solution.

- Stop all running instances: You can stop all the running instances by removing the rows in the management tables for those orchestrators (if you have access to the underlying storage resources). Alternatively, you can restart all the orchestrators using the features exposed by the platform. We will see those features in the next chapters.

- Deploy the new version side-by-side with the previous one: In this scenario, you can use different storage accounts for different function versions, keeping each version isolated from the other.

If you are deploying your functions in Azure, you can use deployment slots provided by the Azure Functions platform to deploy multiple versions of your functions in isolated environments.

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.