CHAPTER 4

Durable Entities

One of the most important stateful patterns in computer science is the aggregator pattern. In the aggregator pattern, you want to implement something that receives multiple calls from the outside, aggregates all the data it receives in an internal status, and manages the status persistence.

If you want to implement this pattern using Azure Functions, you will run into some issues:

- Every function execution is different from the others. Every function execution is a different instance, potentially running in a different server. For this reason, you need to store its status outside your function, and you need to take care of the persistence layer.

- In this kind of scenario, the data order you receive is important, and you may receive lots of data in a small amount of time. Therefore, you need to guarantee the order of what you receive. Because you cannot avoid multiple instances of the same function related to the same aggregator running simultaneously, you need to manage the concurrency in the saving operation of the state. You need to manage this consistency at the persistence layer.

Imagine you want to implement an Azure function that allows you to store the telemetry data from an IoT field device. The following figure shows the pattern.

Figure 26: The aggregator pattern

We suppose that every device must have these features:

- It receives several telemetries at regular intervals.

- It must store and manage the telemetries in chronological order.

- It can have an internal logic to analyze the telemetry in search of anomalies and, if necessary, send notification of the situation to external services.

- It must expose APIs for retrieving telemetry and for setting configuration.

- We can have devices with different behavior with the least possible impact on the code.

The Durable Functions platform provides us with special durable functions called durable entities, or entity functions. In the following paragraphs, we will see in detail the characteristics of these particular functions and how they can help us. Later in this chapter, we will see the full implementation for an IoT platform based on the durable entities.

General concepts

Before starting with the implementation of our devices, it is important to clarify some fundamental concepts regarding durable entities.

A durable entity is similar to an orchestrator. It is an Azure function with a special trigger (the EntityTrigger). Like an orchestrator, a durable entity manages its state abstracting the persistence layer.

You can consider a durable entity like a little service that communicates using messages. It has a unique identity and an internal state, and it exposes operations. It can interact with other entities, orchestrators, or external services.

We saw in the previous chapters that you can access an orchestrator using its orchestrator ID.

You can access a durable entity using a unique identifier called entityID. This identifier is essentially composed of two strings:

- Entity Name: The name of the entity. This name must be the name you define for the entity function that implements the entity. For example, if we implement our device with an entity function called TemperatureDeviceEntity, we will use that string as entity name.

- Entity Key: A string that uniquely identifies a specific entity. You can use a friendly name, a GUID, or whatever string you want.

In our example, suppose we implement one device with an entity function called TelemetryDeviceEntity, and we have two different devices in our environment called livingRoom and kitchen. The platform will uniquely identify the devices with the following entity ID: @TemperatureDeviceEntity@livingRoom and @TemperatureDeviceEntity@kitchen.

A durable entity can expose several operations, and you need the following information to call a specific operation:

- EntityId: It is the entity ID of the target entity. As we said previously, an entityId allows you to address one and only one entity.

- Operation Name: It is a string that identifies the operation to call. For example, our device can have TelemetryReceived or SetConfiguration operations.

- Operation input: This is the parameter (optional) you need to pass to the operation. For example, the TelemetryReceived operation of our device can have the telemetry object as input.

- Scheduled time: This is optional and allows you to schedule the operation.

You can call an operation from different sources (a client, another entity, or an orchestrator), and you have several ways to do that. We will cover those ways in the "Accessing the entities" section.

An entity operation can change the entity's inner status or call another entity and return a value.

Entity definition: function-based vs. class-based

You can define your durable entity in two different ways:

- Function-based syntax: You implement your entity as a function, and the operations provided by the entities are dispatched inside that function.

- Class-based syntax: You design your entity as a class with several methods, and every method can be one operation exposed by your entity.

Function-based syntax

You define a function with a special trigger (EntityTrigger), and you manage your entity state inside that function.

In the following snippet of code, you can see an example of a simple counter implemented using this approach.

Code Listing 33: The counter entity implemented with the function-based syntax

[FunctionName("CounterFunctionBased")] public static void Counter([EntityTrigger] IDurableEntityContext ctx) { switch (ctx.OperationName.ToLowerInvariant()) { case "add": ctx.SetState(ctx.GetState<int>() + ctx.GetInput<int>()); break; case "reset": ctx.SetState(0); break; case "get": ctx.Return(ctx.GetState<int>()); break; } } |

The function uses IDurableEntityContext to manage the input data from the caller, the data to return (if you need it), and the entity's state.

The context interface allows you to set and get the status, and it abstracts the persistence layer. You can store only one object in the state (the platform serializes and deserializes it for you before and after every persistence operation). If you need a complex state object, you must declare and use a class to store the state instead of using a base type like an integer.

If you look at Code Listing 33, you can see that the function implements a switch to manage every single operation supported by the entity. Every branch of the switch manages a single operation and uses the context to retrieve the input data, retrieve the state, and save the state.

The context interface also gives you other methods to call orchestrators or other entities and provides you with all the information about the EntityId invoked. Using the context, you can implement the behavior you prefer for your entity.

This approach works well when:

- You need to provide a dynamic set of operations. Because a string in the function code identifies every operation, you can provide a set of names that change depending on the scenario.

- You have a simple state. The status is simple in our example, but if you have a more complex object, or you need multiple objects in your state, your code grows in complexity.

- You have few operations. If the number of your entity operations is three, like in our example, you can manage them easily, but if the number grows, your code becomes more complex.

The limitations of this approach are:

- Its syntax (based on strings for the operation name) is difficult to maintain and doesn't allow you to have a compile-time check.

- The code isn't readable, and its evolution may be difficult.

You need to manage the retrieving and saving state operations using the context interface. It abstracts the actual persistence operations (you don't see the underlying storage layer), but you explicitly call the GetStatus and SetStatus methods.

Class-based syntax

You can use the function-based syntax for your durable entities if your entity has a simple state or exposes few methods.

In the real world, you often have entities with a complex state (composed of more than one complex object), you need to expose a lot of methods, or more simply, you want to take advantage of the compilation features of the language that you are using such as the compile-time syntax check or the IntelliSense.

In those scenarios, you can implement your durable entity using the class-based syntax. A class-based syntax entity is a POCO class (POCO stands for plain old CLR object) with properties, methods, and one entity function (similar to the entity function you see earlier in the function-based syntax).

This class doesn't require a special hierarchy (you can create your own class structure). It only requires that:

- It must be constructible (it must have at least one public constructor).

- It must be JSON serializable.

The platform automatically serializes and deserializes every single entity instance to store the status on the underlying storage layer. All its serializable properties represent the inner state (so you can design the entity state as a composition of complex objects).

You have some limitations on how you can implement the methods, and in particular:

- A method must have zero or one argument.

- You cannot use overloading, so you cannot have two methods with the same name but different types or arguments.

- You cannot use generics in the method definition.

- Arguments and return values must be JSON serializable.

The entity class exposes an entity function you can use to call the methods provided by the class. When you use your entity in a durable context, you don't call its methods directly. You call the entity function, and it invokes your particular method.

You can read or update the entity state by reading or changing the value in one or more properties in an entity method. The platform stores the state in the storage immediately after your method is finished. Moreover, in a method, you can perform I/O operations or computational operations: the limits are the common limits of Azure functions.

Finally, in an entity method, you can use the entity context (for example, to call another entity or create a new orchestration) through the Entity.Context object.

The following code listing shows you the implementation of the Counter entity.

Code Listing 34: The Counter entity implemented with the function-based syntax

[JsonObject(MemberSerialization.OptIn)] public class Counter { [JsonProperty("value")] public int CurrentValue { get; set; } public void Add(int amount) => this.CurrentValue += amount; public void Reset() => this.CurrentValue = 0; public int Get() => this.CurrentValue; [FunctionName(nameof(Counter))] public static Task Run([EntityTrigger] IDurableEntityContext ctx) => ctx.DispatchAsync<Counter>(); } |

As you can see, the device class consists of:

- A set of properties: They map the inner status you want to manage. In the previous code, for example, we define the CurrentValue property to store the value of the counter. You can use complex objects to store complex values in your state.

- A set of public methods: They can be invoked from outside the entity using the entity function.

- A set of private methods: You can use private methods to implement internal features. We don’t implement any private methods in the previous example because it is simple.

- An entity function: The platform uses it to manage the calls from outside the entity directed to the entity.

If you look at the entity function, you can see that this function uses the durable context to dispatch the calls received by the entity to the correct method without implementing any switch in the code. The DispatchAsync method uses the call context provided by the platform to try to invoke the method in the class. Here you don't have any string as happened in the function-based syntax, so the possibility for error is less.

The name of the entity function (declared in the FunctionName attribute) is also the entity's name. You can have different names for the class and the entity.

A durable entity can implement an interface. In that way, you can create a polymorphism in the durable entities platform.

The following code listing shows you the interface for the counter.

Code Listing 35: The Counter interface

public interface ICounter { void Add(int amount); Task AddAsync(int amount); Task ResetAsync(); Task<int> GetAsync(); } [JsonObject(MemberSerialization.OptIn)] public class Counter : ICounter { [JsonProperty("value")] public int CurrentValue { get; set; } public void Add(int amount) => this.CurrentValue += amount; public Task AddAsync(int amount) { this.Add(amount); return Task.CompletedTask; } public Task ResetAsync() { this.CurrentValue = 0; return Task.CompletedTask; } public Task<int> GetAsync() => Task.FromResult(this.CurrentValue); [FunctionName(nameof(Counter))] public static Task Run([EntityTrigger] IDurableEntityContext ctx) => ctx.DispatchAsync<Counter>(); } |

When you use an interface, you have some other limitations on the methods you can define:

- The entity interface can only have methods.

- The entity interface cannot use generic parameters.

- The entity interface methods must not have more than one parameter.

- An interface method must return a void, Task, or Task<T> value.

If you define a void method, you can only call that method using a fire-and-forget pattern (a one-way call). A Task or Task<T> method can call both one-way and two-way patterns. You call those methods using the two-way pattern when you want to receive a result. We look at both patterns in the next section.

Accessing the entities

You can invoke an entity in two different ways:

- Calling: It is a two-way (round-trip) communication. You call one method exposed by the entity and wait for the method completion. The entity can return a value or not, or it can throw an exception (an error code in JavaScript). In the case of the exception, it will be caught by the caller.

- Signaling: It is a one-way (fire and forget) communication. You call a method exposed by the entity, but you don't wait for a response. In this scenario, the platform delivers your call to the entities, but you cannot know if the method throws an error.

An entity can be accessed by client functions, orchestrator functions, and other entities, and the way to call the entity depends on the caller.

A client function can call an entity using a one-way approach or can retrieve the entity state.

An orchestrator function can use both one-way and two-way patterns.

An entity can only signal another entity.

Accessing the entity from a client function

A client function can signal an entity or read its status.

The following snippet of code shows you how you can use the one-way approach inside a client function.

Code Listing 36: A client function signals an entity

[FunctionName("AddFromQueue")] public static Task AddFromQueue([QueueTrigger("durable-function-trigger")] string input, [DurableClient] IDurableEntityClient client) { // Entity operation input comes from the queue message content. var entityId = new EntityId(nameof(Counter), "myCounter"); int amount = int.Parse(input); return client.SignalEntityAsync(entityId, "Add", amount); } |

The client function is triggered by a message in the durable-function-trigger queue.

It creates the EntityId object for the entity to signal to and calls the SignalEntityAsync method provided by the IDurableEntityClient interface.

The entity invocation is completely asynchronous: you cannot know when the destination entity will process the request.

The IDurableEntityClient interface used by the client provides you with all the methods you need to interact with an entity inside a client.

In the following figure, you can see the methods exposed by the interface.

Figure 27: The IDurableEntityClient interface structure

It is important to know how this interface works.

The SignalEntityAsync allows you to create a one-way communication between your client and an entity, and you have six different overloads of this method. Two of those overloads (one is used in the previous snippet of code) allow you to call a method of the entity knowing the entityId and the method's name (a string). One of those also allows you to signal the entity delayed: you can specify a DateTime object, and the method will signal the entity at that time.

Both the overloads use a string to identify the method, which can create some issues when you refactor your code. If you change the name of an entity method, the compiler will not give you any information that the name you are using in the SignalEntityAsync is wrong. You can determine that only at runtime.

If your entity implements an interface (as mentioned earlier in this chapter), you can use one of the other signatures of the method.

Code Listing 37: A client function signals an entity through an interface

[FunctionName("AddFromQueueWithInterface")] public static Task AddFromQueueWithInterface([QueueTrigger("durable-function-trigger")] string input, [DurableClient] IDurableEntityClient client) { // Entity operation input comes from the queue message content. var entityId = new EntityId(nameof(Counter), "myCounter"); int amount = int.Parse(input); return client.SignalEntityAsync<ICounter>(entityId, c => c.Add(amount)); } |

In this case, you use a lambda expression to identify the entity method you want to signal, and the compiler will give you a compile-time error if you miss the method name. This is one reason why defining and using an interface for your entities is a best practice.

Using the IDurableEntityClient interface, you can also read the state of an entity.

Code Listing 38: A client function reads the entity state

[FunctionName("GetCounterState")] public static async Task<IActionResult> GetCounterState( [HttpTrigger(AuthorizationLevel.Function, Route = "counters/{counterName}")] HttpRequest req, string counterName, [DurableClient] IDurableEntityClient client) { var entityId = new EntityId(nameof(Counter), counterName); EntityStateResponse<JObject> stateResponse = await client.ReadEntityStateAsync<JObject>(entityId); return new OkObjectResult(stateResponse.EntityState); } |

The EntityStateResponse object contains the state of the entity. You can use your class as a generic parameter in the ReadEntityStateAsync method if you want to deserialize the status in your custom object. In the sample, we retrieve the status as JObject. The JObject class can contain complex objects serialized in JSON format.

If you look at Figure 27, you can see another two methods exposed by the IDurableEntityClient interface. The ListEntitiesAsync method allows you to retrieve the list of all the entities in the platform.

Code Listing 39: A client function to retrieve all the counter entities

public class CounterQueryState { public string Key { get; set; } public int Value { get; set; } } [FunctionName("CounterList")] public static async Task<IActionResult> CounterList( [HttpTrigger(AuthorizationLevel.Function, Route = "counters")] HttpRequest req, [DurableClient] IDurableEntityClient client) { var responseList = new List<CounterQueryState>(); var queryDefinition = new EntityQuery() { PageSize = 100, FetchState = true, EntityName = nameof(Counter) }; do { EntityQueryResult queryResult = await client.ListEntitiesAsync(queryDefinition, default); foreach (var item in queryResult.Entities) { var counterState = item.State.ToObject<CounterQueryState>(); counterState.Key = item.EntityId.EntityKey; responseList.Add(counterState); } queryDefinition.ContinuationToken = queryResult.ContinuationToken; } while (queryDefinition.ContinuationToken != null ); return new OkObjectResult(responseList); } |

You create an EntityQuery object that allows you to control how you execute the query against the platform. The EntityQuery object allows you to define the page size for each fetch operation (the query in the platform is always paginated), the name of the entity you want to search (if you want), if the query results contain the state of the entities, and so on.

Every time you call the ListEntitiesAsync method, you retrieve a page of the query, and you need to provide the continuation token returned by the previous invocation. You can know if you reach the last page by checking the continuation token. When it is null, you’ve retrieved the last page of the search.

The last method of the IDurableEntityClient interface is CleanEntityStorage. This method allows you to remove all the empty entities in your platform. An empty entity is an entity with no state, not used by other entities (with no active locks) and idle for a configurable amount of time in the durable function settings. This method allows you to clear your persistence storage safely.

Accessing the entity from an orchestrator function

When you use an orchestrator to interact with an entity, you have the most flexibility. You can use both the patterns one-way and two-way inside a workflow. An orchestrator can signal an entity without waiting for the response. Still, because the platform can manage the workflow state and restart the orchestrator, it can wait for a response from the entity. From this point of view, calling an entity is equal to calling an activity.

The orchestration context (provided by the platform through the OrchestrationTrigger) gives you all the methods you need to interact with entities.

In the following figure, you can see the structure of the IDurableOrchestrationContext interface.

Figure 28: The IDurableOrchestrationContext interface structure

In the following snippet of code, you can see an example of an orchestrator that calls an entity waiting for the response, and then interacts with the same entity with a one-way approach.

Code Listing 40: Interaction between an orchestrator and an entity

[FunctionName("CounterOrchestration")] public static async Task CounterOrchestration([OrchestrationTrigger] IDurableOrchestrationContext context) { var counterName = context.GetInput<string>(); var entityId = new EntityId(nameof(Counter), counterName); int currentValue = await context.CallEntityAsync<int>(entityId, "Get"); if (currentValue < 10) { context.SignalEntity(entityId, "Add", 1); } } |

The orchestrator executes these operations:

- Retrieves the name of the counter entity passed by the client (GetInput method) with which to interact.

- Creates the entityId to identify the entity with which to interact uniquely.

- Calls the Get method of the entity and waits for the result (CallEntityAsync method).

- Based on the result of the previous call, signals the entity for the Add method (SignalEntity method).

Code Listing 40 is easy to understand, but it has a big issue. The names of the operations you want to call or signal in the entity are strings, and you cannot leverage the compiler checking at compile time. If you make a mistake entering one of the names, you have an error at runtime.

To avoid this, you can use the entity interface and you can create a proxy for the entity you want to interact with, as shown in the following code.

Code Listing 41: Interaction between an orchestrator and an entity using the entity interface

[FunctionName("CounterOrchestrationWithProxy")] public static async Task CounterOrchestrationWithProxy([OrchestrationTrigger] IDurableOrchestrationContext context) { var counterName = context.GetInput<string>(); var entityId = new EntityId(nameof(Counter), counterName); var entityProxy = context.CreateEntityProxy<ICounter>(entityId); int currentValue = await entityProxy.GetAsync(); if (currentValue < 10) { entityProxy.Add(1); } } |

The CreateEntityProxy method enables you to create a proxy that exposes the entity interface you want (in the previous snippet of code, the ICounter interface). You can use this proxy to call the entity's methods directly.

As you can see in the snippet, the CallEntityAsync method of the orchestrator context is substituted with the Get method of the ICounter interface, and the SignalEntity method with the Add. If you save the result of the method (like in the Get method of the previous snippet), you are waiting for the response, so you are using a two-way approach. If you don't store the result of a method (like in the Add method invocation), you are using the one-way pattern.

The code is clearer and more maintainable, and you avoid having runtime errors by mistaking the names of the methods.

Another helpful scenario may be the coordination between entities. In some use cases, you must interact with more than one entity simultaneously, and you want other functions not to modify the entities involved in your task.

The orchestration context interface provides you with a lock implementation to implement those scenarios. At the time of writing this book, unfortunately, this feature is only present for durable functions written in .NET.

In the following snippet of code, you can see an example of a lock between two counter entities.

Code Listing 42: Use of the LockAsync method of the IDurableOrchestrationContext

[FunctionName("AddCounterValue")] public static async Task AddCounterValue([OrchestrationTrigger] IDurableOrchestrationContext context) { var counters = context.GetInput<string>(); if (string.IsNullOrWhiteSpace(counters)) return; var counterNames = counters.Split("|"); if (counterNames.Count() != 2) return; var sourceEntityId = new EntityId(nameof(Counter), counterNames[0]); var destEntityId = new EntityId(nameof(Counter), counterNames[1]); using (await context.LockAsync(sourceEntityId, destEntityId)) { ICounter sourceProxy = context.CreateEntityProxy<ICounter>(sourceEntityId); ICounter destProxy = context.CreateEntityProxy<ICounter>(destEntityId); var sourceValue = await sourceProxy.GetAsync(); await destProxy.AddAsync(sourceValue); await sourceProxy.AddAsync(-sourceValue); } } |

The orchestrator retrieves the value in the state of a source counter entity, adds that value to a destination counter entity, and subtracts it from the source entity. The platform will perform all the operations with a lock on the source and destination entities. This means that other orchestrations or entities cannot interact with the same entities while the lock is active.

The LockAsync method creates a critical section in the orchestrator and returns an IDisposable object. You can use the using construct or call the Dispose method explicitly to end the critical section and release all the locks on the entities involved in the operation. When you create a lock with the LockAsync method, the platform sends a "lock" message to all the entities and waits for the "lock acquired" confirmation.

When an entity is locked, every other operation it receives will be placed in the pending operation queue. When the platform releases the lock, the entity will process all the pending operations. The platform persists the lock in the entity state.

Remember that this isn't a transaction. The critical section doesn't automatically roll back the state of the entities involved in the section. It just prevents other functions from modifying the state while you are working on those entities. You must implement your rollback logic if you need it.

There are some limitations with critical sections:

- You cannot create a critical section in another critical section or nest critical sections.

- An orchestrator cannot call another orchestrator in a critical section.

- Inside a critical section, you can call or signal only the entities you locked.

- You cannot call the same entities with parallel calls in a critical section.

If you violate one of the previous limitations, you receive a runtime error (a LockingRulesViolationException).

Accessing an entity from an entity

You can interact with an entity from another entity, but you can only use the one-way pattern: an entity can only signal another entity.

The entity context (both in a function-based syntax using the trigger of the function, and in the class-based syntax using the Entity.Current property) provides you with the SignalEntity method to achieve that.

To give an example, suppose you want to monitor how many times your counter is called by the ResetAsync method. Of course, you can add a new property in the state that takes care of that number, but this information is related to the counter without belonging to it. It is monitoring information, so the best approach may be to create another entity called MonitorEntity to take care of all the monitoring information you want to store.

In the following snippet of code, you can see a simple implementation of the MonitorEntity.

Code Listing 43: A simple MonitorEntity entity

public interface IMonitorEntity { void MethodCalled(string methodName); } [JsonObject(MemberSerialization.OptIn)] public class MonitorEntity : IMonitorEntity { [JsonProperty("methodsCounters")] public Dictionary<string, int> MethodsCounters { get; set; } public void MethodCalled(string methodName) { if (MethodsCounters == null) MethodsCounters = new Dictionary<string, int>(); if (MethodsCounters.ContainsKey(methodName)) MethodsCounters[methodName]++; else MethodsCounters[methodName] = 1; } [FunctionName(nameof(MonitorEntity))] public static Task Run([EntityTrigger] IDurableEntityContext ctx) => ctx.DispatchAsync<MonitorEntity>(); } |

Now we can modify the method ResetAsync of the Counter entity to signal the MethodCalled operation of the MonitorEntity every time the ResetAsync is executed.

Code Listing 44: Signaling an entity inside an entity

public Task ResetAsync() { this.CurrentValue = 0; // Monitoring all the reset operation signaling in a MonitorEntity. // The monitoring entity has the same key of the counter. var monitorEntityId = new EntityId("MonitorEntity", Entity.Current.EntityId.ToString()); Entity.Current.SignalEntity<IMonitorEntity>(monitorEntityId, m => m.MethodCalled("ResetAsync")); return Task.CompletedTask; } |

Entity state management

The platform abstracts our entities' state persistence, which means the platform saves and retrieves each entity's status when we address it by calling any method.

As we said earlier in this paragraph, our entity class must be serializable because the durable function runtime uses the Json.NET library to serialize the entire class in the underlying storage.

Note: The Json.NET package is available for download here, and you can read full documentation about it here.

To control how the runtime serializes our class, we can use the attributes present in the Json.NET library. If we look at Code Listing 35, we can see that in the Counter class, we use two different attributes:

- JsonObject: This attribute allows us to control how Json.NET will serialize the class in the storage. With the MemberSerialization equal to OptIn, only the class members marked with the attribute JsonProperty (or DataMember) will be serialized. OptOut allows you to serialize all the members except for that member marked with the JsonIgnore attribute.

- JsonProperty: This attribute allows you to explicitly mark the member you want to serialize (and if you want to define the name of the JSON property in the serialization).

You can use all the serialization attributes provided by Json.NET. For example, you can use the JsonIgnore attribute to prevent Json.NET from serializing a specific member.

The previous attributes aren't mandatory. Our entity is a standard class, and the Json.NET manages it even if you don't decorate the class member. If you like, you can use the DataContract and DataMember attributes, as shown in the following code.

Code Listing 45: The counter class decorated using DataContract

[DataContract] public class CounterDataMember { [DataMember(Name = "value")] public int CurrentValue { get; set; } ..... } |

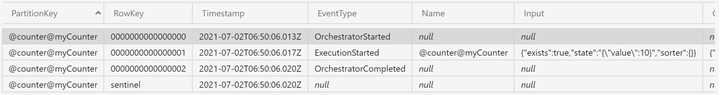

The runtime manages the entity function executions in the same way it manages an orchestrator. It uses the TaskHubHistory table to store each step the entities did. So, for example, if we call the Add method of the Counter entity myCounter, the result is shown in the following figure.

Figure 29: myCounter history table for Add execution

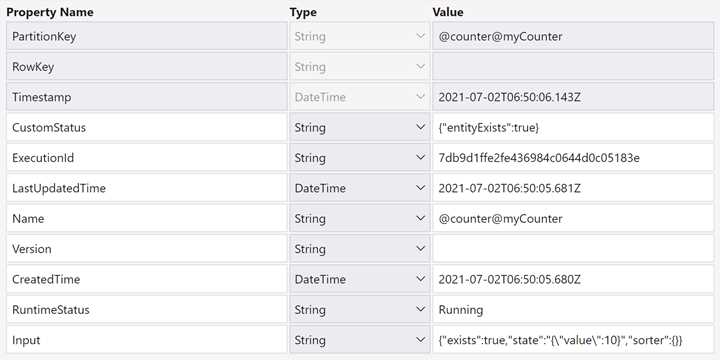

The runtime uses the TaskHubInstances table to store the current status of every entity. In the following figure, you can see the myCounter status after the Add invocation.

Figure 30: The current status of myCounter in the TaskHubInstances

As you can see, the runtime uses the Input field to store the serialization of your class (in the state property of the complex object stored in the field).

State and versioning

In the real world, your project evolves, and you may need to modify the class that implements your entity. As the entity state is serialized in JSON format within the storage, you need to pay attention to some scenarios:

- You add a new property in your class. In this case, that property isn't in the current status stored in the storage, and it will assume the default value when your entity is recovered.

- You remove a property in the class, and the property is in the serialization on the storage. In this case, the value in that property will be lost next time you interact with that entity.

- You rename a property in the class. The result is the same as when removing a property, and the "new" property will assume the default value the first time you interact with it.

- You change the type of property. In this case, you can have two different behaviors. If the runtime can deserialize the old type in the new one (for example, you have an integer property and change it to double), it can recreate the status, and nothing happened. If the runtime cannot deserialize the old type in the new one, an exception will occur when you try to interact with the entity.

Because the runtime is using Json.NET, you can use all the options in Json.NET to control the serialization of the objects. You can write your own code to deserialize the JSON in the status as you prefer.

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.