CHAPTER 1

Introduction

About this book

This is a book about building multitenant applications using ASP.NET. We will be discussing what multitenancy means for a web application in general, and then we’ll be looking at how ASP.NET frameworks like Web Forms and MVC can help us implement multitenant solutions.

You can expect to find here working solutions for the problems outlined, some of which certainly can be enhanced and evolved. Whenever appropriate, I will leave references so that interested readers can improve upon what I’ve built and further their understanding of these matters.

Some knowledge of ASP.NET (Web Forms or MVC) is required, but you do not have to be an expert. Hopefully, both beginners and experts will find something they can use here.

Throughout the book, we will be referring to two imaginary tenants/domains, ABC.com and XYZ.net, which will both be hosted in our server.

What is multitenancy and why should you care?

Multitenancy is a concept that has gained some notoriety in the last years as an alternative to multiple deployments. The concept is simple: a single web application can respond to clients in a way that can make them think they are talking to different applications. The different “faces” of this application are called tenants, because conceptually they live in the same space—the web application—and can be addressed individually. Tenants can be added or removed just by the flip of a configuration switch.

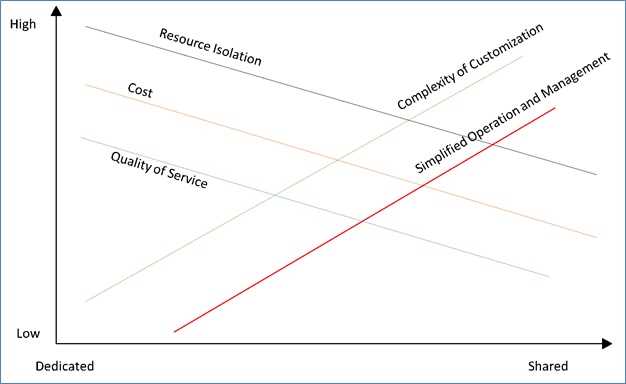

Why is this useful? Well, for one, it renders it unnecessary to have multiple servers online, with all the maintenance and costs they require. In general, among other things, one has to consider the following:

- Resource isolation: A dedicated server is better shielded from failures in other infrastructure components than a shared solution.

- Cost: Costs are higher when we need to have one physical server per service, application, or customer than with a shared server.

- Quality of service: You can achieve a higher level of quality and customization if you have separate servers, because you are not concerned with how it might affect different services, applications, or customers.

- Complexity of customization: We must take extra care in customizing multitenant solutions because we typically don’t want things to apply to all tenants in the same way.

- Operation and management: “Hard” management, like backups, monitoring, physical allocation, power supplies, cooling, etc., are much easier when we only have one server.

- Decision criteria for dedicated versus shared (multitenant) deployments

In general, a multitenant framework should help us handle the following problems:

- Branding: Different brandings for different tenants; by branding I mean things like logo images, stylesheets, and layout in general.

- Authentication: Different tenants should have different user registrations; a user registered in a specific tenant should not be able to login to another tenant.

- Workflow: It makes sense that different tenants handle the same basic things in a (slightly) different way; a multitenant framework is supposed to make this as transparent as possible with regard to code.

- Data Model: Different tenants may have (slightly) different data needs; again, we should accommodate this need when possible, considering that we are talking about the same shared application.

Throughout the book we will give some attention to these problems.

Multitenancy requirements

As high-level requirements, our application framework should be able to:

- Load a number of tenants and their information automatically

- Identify, from each HTTP request, the tenant that it was meant to, or use a fallback value

- Apply a branding theme to each tenant’s requested pages

- Allow users to log in only to the tenant they are associated with

- Offer common application services to all tenants that don’t collide; for example, something stored in application cache for one tenant will not be overwritten by another tenant

Application services

Application services offer common functionality that .NET/ASP.NET provides out of the box, but not in a multitenant way. These will be discussed in Chapter 9, “Application Services.”

Frameworks

ASP.NET is an umbrella under which different frameworks coexist: while the venerable Web Forms was the first public implementation that Microsoft put out, MVC has gained a lot of momentum since its introduction, and is now considered by some as a more modern approach to web development. SharePoint is also a strong contender, and even more so with SharePoint Online, part of the Office 365 product. Now it seems that OWIN (and Katana) is the new cool kid on the block, and some of the most recent frameworks that Redmond introduced recently even depend on it (take SignalR, for example).

On the data side, Entity Framework Code First is now the standard for data access using the Microsoft .NET framework, but other equally solid—and some would argue, even stronger—alternatives exist, such as NHibernate, and we will cover these too.

Authentication has also evolved from the venerable, but outdated, provider mechanism introduced in ASP.NET 2. A number of Microsoft (or otherwise) sponsored frameworks and standards (think OAuth) have been introduced, and the developer community certainly welcomes them. Here we will talk about the Identity framework, Microsoft’s most recent authentication framework, designed to replace the old ASP.NET 2 providers and the Simple Membership API introduced in MVC 4 (not covered since it has become somewhat obsolete with the introduction of Identity).

Finally, the glue that will hold these things together, plus the code that we will be producing, is Unity, Microsoft’s Inversion of Control (IoC), Dependendy Injection (DI), and Aspect-Oriented Programming (AOP) framework. This is mostly because I have experience with Unity, but, by all means, you are free to use whatever IoC framework you like. Unity is only used for registering components; its retrieval is done through the Common Service Locator, a standard API that most IoC frameworks comply to. Most of the code will work with any other framework that you choose, provided it offers (or you roll out your own) integration with the Common Service Locator. Except the component registration code, which can be traced to a single bootstrap method, all the rest of the code relies on the Common Service Locator, not a particular IoC framework.

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.