CHAPTER 3

Concepts

Who do you want to talk to?

As we’ve seen, the main premise of multitenancy is that we can respond differently to different tenants. You might have asked yourself: how does the ASP.NET know which tenant’s contents it should be serving? That is, who is the client trying to reach? How can ASP.NET find out?

There may be several answers to this question:

- From the requested host name; for example, if the browser is trying to reach abc.com or xyz.net, as stated in the request URL

- From a query string parameter, like http://host.com?tenant=abc.com

- From the originating (client) host IP address

- From the originating client’s domain name

Probably the most typical (and useful) use case is the first one; you have a single web server (or server farm) which has several DNS records (A or CNAME) assigned to it, and it will respond differently depending on how it was reached, say, abc.com and xyz.net. Being developers, let’s try to define a generic contract that can give an answer to this question. Consider the following method signature:

Code Sample 5

String GetCurrentTenant(RequestContext context) |

We can interpret it as: “given some request, give me the name of the corresponding tenant.”

Note: If you want to know the difference between DNS A and CNAME records, you can find a good explanation here

The RequestContext class is part of the System.Web.Routing namespace, and it encapsulates all of a request’s properties and context. Its HttpContext property allows easy access to the common HTTP request URL, server variables, query string parameters, cookies and headers and RouteData to routing information, if available. I chose this class for the request instead of what might be more obvious ones—HttpContext and HttpContextBase—precisely because it eases access to route data, in case we need it.

Note: HttpContextBase was introduced in .NET 3.5 to allow easy mocking, because it is not sealed, and outside of the ASP.NET pipeline. It basically mimics the properties and behavior of HttpContext, which is sealed.

As for the return type, it will be the name of a tenant. More on that later.

In the .NET world, we have two main options if we are to reuse such a method signature:

- Define a method delegate

- Define an interface or an abstract base class

In our case, we’ll go with an interface, enter ITenantIdentifierStrategy:

Code Sample 6

public interface ITenantIdentifierStrategy { String GetCurrentTenant(RequestContext context); } |

Host header strategy

- Host header strategy

A simple implementation of ITenantIdentifierStrategy for using the requested host name (Host HTTP header) as the tenant identifier is probably the one you’ll use more often in public-facing sites. A single server with a single IP address and multiple host and domain names will differentiate tenants by the requested host, in the HTTP request:

Table 1: Mapping of HTTP Host headers to tenants

HTTP Request Headers | Tenant |

|---|---|

GET /Default.aspx HTTP/1.1 Host: abc.com | abc.com |

GET /Default.aspx HTTP/1.1 Host: xyz.net | xyz.net |

Note: For more information on the Host HTTP header, see RFC 2616, HTTP Header Field Definitions.

A class for using the host header as the tenant name might look like the following:

Code Sample 7

public class HostHeaderTenantIdentifierStrategy : ITenantIdentifierStrategy { public String GetCurrentTenant(RequestContext context) { return context.HttpContext.Request.Url.Host.ToLower(); } } |

Tip: This code is meant for demo purposes only; it does not have any kind of validation and just returns the requested host name in lowercase. Real-life code should be slightly more complex.

Query string strategy

- Query string strategy

We might want to use a query string parameter to differentiate between tenants, like host.com?tenant=abc.com:

Table 2: Mapping of HTTP query strings to tenants

HTTP Request URL | Tenant |

http://host.com?Tenant=abc.com | abc.com |

http://host.com?Tenant=xyz.net | xyz.net |

This strategy makes it really easy to test with different tenants; no need to configure anything— just pass a query string parameter in the URL.

We can use a class like the following, which picks the Tenant query string parameter and assigns it as the tenant name:

public class QueryStringTenantIdentifierStrategy : ITenantIdentifierStrategy { public String GetCurrentTenant(RequestContext context) { return (context.HttpContext.Request.QueryString["Tenant"] ?? String.Empty).ToLower(); } } |

Tip: Even if this technique may seem interesting at first, it really isn’t appropriate for real-life scenarios. Just consider that for all your internal links and postbacks you will have to make sure to add the Tenant query string parameter; if for whatever reason it is lost, you are dropped out of the desired tenant.

Note: A variation of this pattern could use the HTTP variable PATH_INFO instead of QUERY_STRING, but this would have impacts, namely, with MVC.

Source IP address strategy

- Source IP strategy

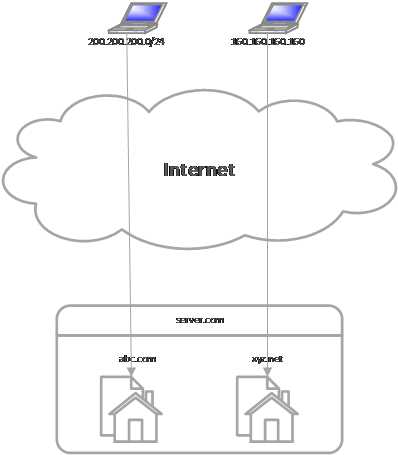

Now suppose we want to determine the tenant’s name from the IP address of the originating request. Say a user located at a network whose address is 200.200.200.0/24 will be assigned tenant abc.com and another one using a static IP of 160.160.160.160 will get xyz.net. It gets slightly trickier, because we need to manually register these assignments, and we need to do some math to find out if a request matches a list of registered network addresses.

We have two possibilities for associating a network address to a tenant name:

- We use a single IP address

- We use an IP network and a subnet mask.

Say, for example:

Table 3: Mapping of source IP addresses to tenants

Source Network / IP | Tenant |

200.200.200.0/24 (200.200.200.1-200.200.200.254) | abc.com |

160.160.160.1 | xyz.net |

The .NET Base Class Library does not offer an out-of-the-box API for IP network address operations, so we have to build our own. Consider the following helper methods:

Code Sample 8

public static class SubnetMask { public static IPAddress CreateByHostBitLength(Int32 hostPartLength) { var binaryMask = new Byte[4]; var netPartLength = 32 - hostPartLength; if (netPartLength < 2) { throw new ArgumentException ("Number of hosts is too large for IPv4."); } for (var i = 0; i < 4; i++) { if (i * 8 + 8 <= netPartLength) { binaryMask[i] = (Byte) 255; } else if (i * 8 > netPartLength) { binaryMask[i] = (Byte) 0; } else { var oneLength = netPartLength - i * 8; var binaryDigit = String.Empty .PadLeft(oneLength, '1').PadRight(8, '0'); binaryMask[i] = Convert.ToByte(binaryDigit, 2); } } return new IPAddress(binaryMask); }

public static IPAddress CreateByNetBitLength(Int32 netPartLength) { var hostPartLength = 32 - netPartLength; return CreateByHostBitLength(hostPartLength); } public static IPAddress CreateByHostNumber(Int32 numberOfHosts) { var maxNumber = numberOfHosts + 1; var b = Convert.ToString(maxNumber, 2); return CreateByHostBitLength(b.Length); } } public static class IPAddressExtensions { public static IPAddress[] ParseIPAddressAndSubnetMask(String ipAddress) { var ipParts = ipAddress.Split('/'); var parts = new IPAddress[] { ParseIPAddress(ipParts[0]), ParseSubnetMask(ipParts[1]) }; return parts; } public static IPAddress ParseIPAddress(String ipAddress) { return IPAddress.Parse(ipAddress.Split('/').First()); } public static IPAddress ParseSubnetMask(String ipAddress) { var subnetMask = ipAddress.Split('/').Last(); var subnetMaskNumber = 0; if (!Int32.TryParse(subnetMask, out subnetMaskNumber)) { return IPAddress.Parse(subnetMask); } else { return SubnetMask.CreateByNetBitLength(subnetMaskNumber); } }

public static IPAddress GetBroadcastAddress(this IPAddress address, IPAddress subnetMask) { var ipAdressBytes = address.GetAddressBytes(); var subnetMaskBytes = subnetMask.GetAddressBytes(); if (ipAdressBytes.Length != subnetMaskBytes.Length) { throw new ArgumentException ("Lengths of IP address and subnet mask do not match."); } var broadcastAddress = new Byte[ipAdressBytes.Length]; for (var i = 0; i < broadcastAddress.Length; i++) { broadcastAddress[i] = (Byte)(ipAdressBytes[i] | (subnetMaskBytes[i] ^ 255)); } return new IPAddress(broadcastAddress); } public static IPAddress GetNetworkAddress(this IPAddress address, IPAddress subnetMask) { var ipAdressBytes = address.GetAddressBytes(); var subnetMaskBytes = subnetMask.GetAddressBytes(); if (ipAdressBytes.Length != subnetMaskBytes.Length) { throw new ArgumentException ("Lengths of IP address and subnet mask do not match."); } var broadcastAddress = new Byte[ipAdressBytes.Length]; for (var i = 0; i < broadcastAddress.Length; i++) { broadcastAddress[i] = (Byte)(ipAdressBytes[i] & (subnetMaskBytes[i])); } return new IPAddress(broadcastAddress); } public static Boolean IsInSameSubnet(this IPAddress address2, IPAddress address, Int32 hostPartLength) { return IsInSameSubnet(address2, address, SubnetMask .CreateByHostBitLength(hostPartLength)); } public static Boolean IsInSameSubnet(this IPAddress address2, IPAddress address, IPAddress subnetMask) { var network1 = address.GetNetworkAddress(subnetMask); var network2 = address2.GetNetworkAddress(subnetMask); return network1.Equals(network2); } } |

Note: This code is based in code publicly available here (and slightly modified).

Now we can write an implementation of ITenantIdentifierStrategy that allows us to map IP addresses to tenant names:

Code Sample 9

public class SourceIPTenantIdentifierStrategy : ITenantIdentifierStrategy { private readonly Dictionary<Tuple<IPAddress, IPAddress>, String> networks = new Dictionary<Tuple<IPAddress, IPAddress>, String>();

public IPTenantIdentifierStrategy Add(IPAddress ipAddress, Int32 netmaskBits, String name) { return this.Add(ipAddress, SubnetMask.CreateByNetBitLength( netmaskBits), name); } public IPTenantIdentifierStrategy Add(IPAddress ipAddress, IPAddress netmaskAddress, String name) { this.networks [new Tuple<IPAddress, IPAddress>(ipAddress, netmaskAddress)] = name.ToLower(); return this; } public IPTenantIdentifierStrategy Add(IPAddress ipAddress, String name) { return this.Add(ipAddress, null, name); } public String GetCurrentTenant(RequestContext context) { var ip = IPAddress.Parse(context.HttpContext.Request .UserHostAddress); foreach (var entry in this.networks) { if (entry.Key.Item2 == null) { if (ip.Equals(entry.Key.Item1)) { return entry.Value.ToLower(); } } else { if (ip.IsInSameSubnet(entry.Key.Item1, entry.Key.Item2)) { return entry.Value; } } } return null; } } |

Notice that this class is not thread safe; if you wish to make it so, one possibility would be to use a ConcurrentDictionary<TKey, TValue> instead of a plain Dictionary<TKey, TValue>.

Before we can use IPTenantIdentifierStrategy, we need to register some mappings:

Code Sample 10

var s = new SourceIPTenantIdentifierStrategy(); s.Add(IPAddress.Parse("200.200.200.0", 24), "abc.com"); s.Add(IPAddress.Parse("160.160.160.1"), "xyz.net"); |

In this example we see that tenant xyz.net is mapped to a single IP address, 160.160.160.1, while tenant abc.com is mapped to a network of 200.200.200.0 with a 24-bit network mask, meaning all hosts ranging from 200.200.200.1 to 200.200.200.254 will be included.

Source domain strategy

- Source domain strategy

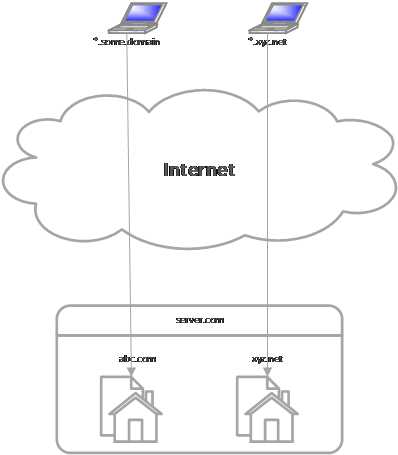

We may not know about IP addresses, but instead, domain names; hence a strategy based on client domain names comes in order. We want to get the tenant’s name from the domain name part of the requesting host, something like:

Table 4: Mapping source domain names to tenants

Source Domain | Tenant |

*.some.domain | abc.com |

*.xyz.net | xyz.net |

Subdomains should also be included. Here’s a possible implementation of such a strategy:

Code Sample 11

public class SourceDomainTenantIdentifierStrategy : ITenantIdentifierStrategy { private readonly Dictionary<String, String> domains = new Dictionary<String, String>(StringComparer.OrdinalIgnoreCase); public DomainTenantIdentifierStrategy Add(String domain, String name) { this.domains[domain] = name; return this; } public DomainTenantIdentifierStrategy Add(String domain) { return this.Add(domain, domain); } public String GetCurrentTenant(RequestContext context) { var hostName = context.HttpContext.Request.UserHostName; var domainName = String.Join(".", hostName.Split('.') .Skip(1)).ToLower(); return this.domains.Where(domain => domain.Key == domainName) .Select(domain => domain.Value).FirstOrDefault(); } } |

For DomainTenantIdentifierStrategy, of course, we also need to enter some mappings:

Code Sample 12

var s = new SourceDomainTenantIdentifierStrategy(); s.Add("some.domain", "abc.com"); s.Add("xyz.net"); |

The first entry maps all client requests coming from the some.domain domain (or a subdomain of) to a tenant named abc.com. The second does an identical operation for the xyz.net domain, where we skip the tenant’s name because it should be identical to the domain name.

As you can see, two of the previous strategies’ implementations—host header and query string parameter—are basically stateless and immutable, so instead of creating new instances every time, we can instead have static instances of each in a well-known location. Let’s create a structure for that purpose:

Code Sample 13

public static class TenantsConfiguration { public static class Identifiers { public static readonly HostHeaderTenantIdentifierStrategy HostHeader = new HostHeaderTenantIdentifierStrategy(); public static readonly QueryStringTenantIdentifierStrategy QueryString = new QueryStringTenantIdentifierStrategy(); } |

Tip: Notice the DefaultTenant property. This is what will be used if the tenant identification strategy is unable to map a request to a tenant.

Two other strategies—by source IP address and by domain name—require configuration, so we shouldn’t have them as constant instances, but, to allow for easy finding, let’s add some static factories to the TenantsConfiguration class introduced just now:

Code Sample 14

public static class TenantsConfiguration { //rest goes here public static class Identifiers { //rest goes here public static SourceDomainTenantIdentifierStrategy SourceDomain() { return new SourceDomainTenantIdentifierStrategy(); } public static SourceIPTenantIdentifierStrategy SourceIP() { return new SourceIPTenantIdentifierStrategy(); } } } |

Note: In Chapter 12,we will see how all these strategies are related.

Getting the current tenant

We’ve looked at some strategies for obtaining the tenant’s name from the request; now, we have to pick one, and store it somewhere where it can be easily found.

Static property

One option is to store this as a static property in the TenantsConfiguration class:

Code Sample 15

public static class TenantsConfiguration { public static ITenantIdentifierStrategy TenantIdentifier { get; set; } //rest goes here } |

Now, we can choose whatever strategy we want, probably picking one from the TenantsConfiguration’s static members. Also, we need to set the DefaultTenant property, so that if the current strategy is unable to identify the tenant to use, we have a fallback:

Code Sample 16

TenantsConfiguration.TenantIdentifier = TenantsConfiguration.Identifiers.HostHeader; TenantsConfiguration.DefaultTenant = "abc.com"; |

Unity and the Common Service Locator

Another option is to use an Inversion of Control (IoC) framework to store a singleton reference to the tenant identifier instance of our choice. Better yet, we can use the Common Service Locator to abstract away the IoC that we’re using. This way, we are not tied to a particular implementation, and can even change the one to use without impacting the code (except, of course, some bootstrap code). There are several IoC containers for the .NET framework. Next, we’ll see an example using a well-known IoC framework, Microsoft Unity, part of Microsoft’s Enterprise Library. This approach has the advantage that we can register new strategies dynamically through code (or through the Web.config file) without changing any code, should we need to do so. We will be using this approach throughout the book.

Code Sample 17

//set up Unity var unity = new UnityContainer(); //register instances unity.RegisterInstance<ITenantIdentifierStrategy>(TenantsConfiguration.Identifiers.HostHeader); unity.RegisterInstance<String>("DefaultTenant", "abc.com"); //set up Common Service Locator with the Unity instance ServiceLocator.SetLocatorProvider(() => new UnityServiceLocator(unity)); //resolve the tenant identifier strategy and the default tenant var identifier = ServiceLocator.Current.GetInstance<ITenantIdentifierStrategy>(); var defaultTenant = ServiceLocator.Current.GetInstance<String>("DefaultTenant"); |

Chapter 6 also talks about Unity and how to use it to return components specific to the current tenant.

Note: Unity is just one among tens of IoC containers, offering similar functionality as well as more specific ones. Not all have adapters for the Common Service Locator, but it is generally easy to implement one. For a more in-depth discussion of IoC, the Common Service Locator, and Unity, please see Microsoft Unity Succinctly.

What’s in a name?

Now that we have an abstraction that can give us a tenant’s name, let’s think for a moment what else a tenant needs.

We might need a theme as well, something that aggregates things like color schemes and fonts. Different tenants might want different looks.

In the ASP.NET world, the two major frameworks, MVC and Web Forms, offer the concept of master pages or layout pages (in MVC terminology), which are used to define the global layout of an HTML page. With this, it is easy to enforce a consistent layout throughout a site, so, let’s consider a master page (or layout page, in MVC terms) property.

It won’t hurt having a collection of key/value pairs that are specific to a tenant, regardless of having a more advanced configuration functionality, so we now have a general-purpose property bag.

Windows offers a general purpose, operating-system-supported mechanism for monitoring applications: performance counters. Performance counters allow us to monitor in real time certain aspects of our application, and even react automatically to conditions. We shall expose a collection of counter instances to be created automatically in association with a tenant.

It might be useful to offer a general-purpose extension mechanism; before the days IoC became popular, .NET already included a generic interface for resolving a component from a type in the form of the IServiceProvider interface. Let’s also consider a service resolution mechanism using this interface.

Finally, it makes sense to have a tenant initialize itself when it is registering with our framework. This is not data, but behavior.

So, based on what we’ve talked about, our tenant definition interface, ITenantConfiguration, will look like this:

Code Sample 18

public interface ITenantConfiguration { String Name { get; } String Theme { get; } String MasterPage { get; } IServiceProvider ServiceProvider { get; } IDictionary<String, Object> Properties { get; } IEnumerable<String> Counters { get; } void Initialize(); } |

For example, a tenant called xyz.net might have the following configuration:

Code Sample 19

public sealed class XyzNetTenantConfiguration : ITenantConfiguration { public XyzNetTenantConfiguration() { //do something productive this.Properties = new Dictionary<String, Object>(); this.Counters = new List<String> { "C", "D", "E" }; }

public void Initialize() { //do something productive } public String Name { get { return "xyz.net"; } } public String MasterPage { get { return this.Name; } } public String Theme { get { return this.Name; } } public IServiceProvider ServiceProvider { get; private set; } public IDictionary<String, Object> Properties { get; private set; } public IEnumerable<String> Counters { get; private set; } } |

In this example, we are returning a MasterPage and a Theme that are identical to the tenant’s Name, and are not returning anything really useful in the Counters, Properties and ServiceProvider properties, but in real life, you would probably do something else. Any counter names you return will be automatically created as numeric performance counter instances.

Note: There are lots of other options for providing this kind of information, like with attributes, for example.

Finding tenants

Tenant location strategies

What’s a house without someone to inhabit it?

Now, we have to figure out a strategy for finding tenants. Two basic approaches come to mind:

- Manually configuring individual tenants explicitly

- Automatically finding and registering tenants

Again, let’s abstract this functionality in a nice interface, ITenantLocationStrategy:

Code Sample 20

public interface ITenantLocationStrategy { IDictionary<String, Type> GetTenants(); } |

This interface returns a collection of names and types, where the types are instances of some non-abstract class that implements ITenantConfiguration and the names are unique tenant identifiers.

We’ll also keep a static property in TenantsConfiguration, DefaultTenant, where we can store the name of the default tenant, as a fallback if one cannot be identified automatically:

Code Sample 21

public static class TenantsConfiguration { public static String DefaultTenant { get; set; } //rest goes here } |

Here are the strategies for locating and identifying tenants:

Code Sample 22

public static class TenantsConfiguration { public static String DefaultTenant { get; set; } public static ITenantIdentifierStrategy TenantIdentifier { get; set; } public static ITenantLocationStrategy TenantLocation { get; set; } //rest goes here } |

Next, we’ll see some ways to register tenants.

Manually Registering Tenants

Perhaps the most obvious way to register tenants is to have a configuration section in the Web.config file where we can list all the types that implement tenant configurations. We would like to have a simple structure, something like this:

Code Sample 23

<tenants default="abc.com"> <add name="abc.com" type="MyNamespace.AbcComTenantConfiguration, MyAssembly" /> <add name="xyz.net" type="MyNamespace.XyzNetTenantConfiguration, MyAssembly" /> </tenants> |

Inside the tenants section, we have a number of elements containing the following attributes:

- Name: the unique tenant identifier; in this case, it will be the same as the domain name that we wish to answer to (see Host header strategy)

- Type: the fully qualified type name of a class that implements ITenantConfiguration

- Default: the default tenant, if no tenant can be identified from the current tenant identifier strategy

The corresponding configuration classes in .NET are:

Code Sample 24

[Serializable] public class TenantsSection : ConfigurationSection { public static readonly TenantsSection Section = ConfigurationManager .GetSection("tenants") as TenantsSection; [ConfigurationProperty("", IsDefaultCollection = true, IsRequired = true)] public TenantsElementCollection Tenants { get { return base[String.Empty] as TenantsElementCollection; } } } [Serializable] public class TenantsElementCollection : ConfigurationElementCollection, IEnumerable<TenantElement> { protected override String ElementName { get { return String.Empty; } }

protected override ConfigurationElement CreateNewElement() { return new TenantElement(); } protected override Object GetElementKey(ConfigurationElement element) { var elm = element as TenantElement; return String.Concat(elm.Name, ":", elm.Type); } IEnumerator<TenantElement> IEnumerable<TenantElement>.GetEnumerator() { foreach (var elm in this.OfType<TenantElement>()) { yield return elm; } } } [Serializable] public class TenantElement : ConfigurationElement { [ConfigurationProperty("name", IsKey = true, IsRequired = true)] [StringValidator(MinLength = 2)] public String Name { get { return this["name"] as String; } set { this["name"] = value; } }

[ConfigurationProperty("type", IsKey = true, IsRequired = true)] [TypeConverter(typeof(TypeTypeConverter))] public Type Type { get { return this["type"] as Type; } set { this["type"] = value; } } [ConfigurationProperty("default", IsKey = false, IsRequired = false, DefaultValue = false)] public Boolean Default { get { return (Boolean)(this["default"] ?? false); } set { this["default"] = value; } } } |

So, our tenant location strategy (ITenantLocationStrategy) implementation might resemble the following:

Code Sample 25

You might have noticed the Instance field; because there isn’t much point in having several instances of this class, since all point to the same .config file, we can have a single static instance of it, and always use it when necessary. Now, all we have to do is set this strategy as the one to use in TenantsConfiguration. If we are to use the Common Service Locator strategy (see Unity and the Common Service Locator), we need to add the following line in our Unity registration method and TenantsConfiguration static class:

Code Sample 26

public static class TenantsConfiguration { //rest goes here public static class Locations { public static XmlTenantLocationStrategy Xml() { return XmlTenantLocationStrategy.Instance; } //rest goes here } } container.RegisterInstance<ITenantLocationStrategy>(TenantsConfiguration.Locations. Xml()); |

By keeping a factory of all strategies in the TenantsConfiguration class, it is easier for developers to find the strategy they need, from the set of the ones provided out of the box.

Finding tenants automatically

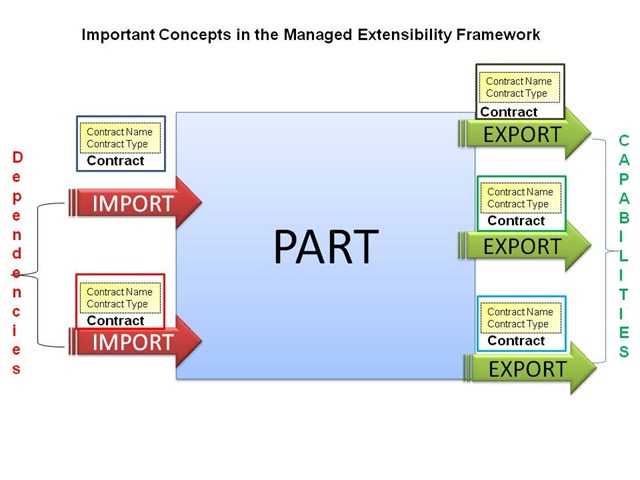

As for finding tenants automatically, there are several alternatives, but I opted for using Microsoft Extensibility Framework (MEF). This is a framework included with .NET that offers mechanisms for automatically locating plug-ins from, among others, the file system. Its concepts include:

- Contract Type: The abstract base class or interface that describes the functionality to import (the plug-in API)

- Contract Name: A free-form name that is used to differentiate between multiple parts of the same contract type

- Part: A concrete class that exports a specific Contract Type and Name and can be found by a Catalog

- Catalog: An MEF class that implements a strategy for finding parts

- MEF architecture

- MEF parts

We won’t go into MEF in depth; we’ll just see how we can use it to find tenant configuration classes automatically in our code. We just need to decorate plug-in classes—in our case, tenant configurations—with a couple of attributes, choose a strategy to use, and MEF will find and optionally instantiate them for us. Let’s see an example of using MEF attributes with a tenant configuration class:

Code Sample 27

[ExportMetadata("Default", true)] [PartCreationPolicy(CreationPolicy.Shared)] [Export("xyz.net", typeof(ITenantConfiguration))] public sealed class XyzNetTenantConfiguration : ITenantConfiguration { public XyzNetTenantConfiguration() { //do something productive this.Properties = new Dictionary<String, Object>(); this.Counters = new List<String> { "C", "D", "E" }; }

public void Initialize() { //do something productive } public String Name { get { return "xyz.net"; } } public String MasterPage { get { return this.Name; } } public String Theme { get { return this.Name; } } public IServiceProvider ServiceProvider { get; private set; } public IDictionary<String, Object> Properties { get; private set; } public IEnumerable<String> Counters { get; private set; } } |

This class is basically identical to one presented in code sample 18, with the addition of the ExportMetadataAttribute, PartCreationPolicyAttribute, and ExportAttribute attributes. These are part of the MEF framework and their purpose is:

- ExportMetadataAttribute: Allows adding custom attributes to a registration; you can add as many of these as you want. These attributes don’t have any special meaning to MEF, and will only be meaningful to classes importing plug-ins.

- PartCreationPolicyAttribute: How the plug-in is going to be created by MEF; currently, two options exist: Shared (for singletons) or NonShared (for transient instances, the default)

- ExportAttribute: Marks a type for exporting as a part. This is the only required attribute.

Now, our implementation of a tenant location strategy using MEF goes like this:

Code Sample 28

public sealed class MefTenantLocationStrategy : ITenantLocationStrategy { private readonly ComposablePartCatalog catalog;

public MefTenantLocationStrategy(params String [] paths) { this.catalog = new AggregateCatalog(paths.Select( path => new DirectoryCatalog(path))); }

public MefTenantLocationStrategy(params Assembly [] assemblies) { this.catalog = new AggregateCatalog(assemblies .Select(asm => new AssemblyCatalog(asm))); }

public IDictionary<String, Type> GetTenants() { //get the default tenant var tenants = this.catalog.GetExports( new ImportDefinition(a => true, null, ImportCardinality.ZeroOrMore, false, false)) .ToList(); var defaultTenant = tenants.SingleOrDefault(x => x.Item2.Metadata .ContainsKey("Default"));

if (defaultTenant != null) { var isDefault = Convert.ToBoolean(defaultTenant.Item2 .Metadata["Default"]); if (isDefault) { if (String.IsNullOrWhiteSpace( TenantsConfiguration.DefaultTenant)) { TenantsConfiguration.DefaultTenant = defaultTenant.Item2.ContractName; } } }

return this.catalog.GetExportedTypes<ITenantConfiguration>(); } } |

This code will look up parts from either a set of assemblies or a set of paths. Then it will try to set a tenant as the default one, if no default is set. Let’s add it to the TenantsConfiguration class:

Code Sample 29

public static class TenantsConfiguration { //rest goes here public static class Locations { public static XmlTenantLocationStrategy Xml() { return XmlTenantLocationStrategy.Instance; } public static MefTenantLocationStrategy Mef (params Assembly[] assemblies) { return new MefTenantLocationStrategy(assemblies); } public static MefTenantLocationStrategy Mef(params String [] paths) { return new MefTenantLocationStrategy(paths); } //rest goes here } } container.RegisterInstance<ITenantLocationStrategy>(TenantsConfiguration.Locations. Mef("some", "path"); |

At the end, we register this implementation as the default tenant location strategy—remember, there can be only one. This will be the instance returned by the Common Service Locator for the ITenantLocationStrategy type.

Bootstrapping tenants

We need to run the bootstrapping code at the start of the web application. We have a couple of options:

- At the Application_Start event of the HttpApplication, normally defined in the Global.asax.cs

- Using the PreApplicationStartMethodAttribute, to run code before Application_Start

In any case, we need to set the strategies and get the tenants list:

Code Sample 30

TenantsConfiguration.DefaultTenant = "abc.com"; TenantsConfiguration.TenantIdentifier = TenantsConfiguration.Identifiers .HostHeader; TenantsConfiguration.TenantLocation = TenantsConfiguration.Locations.Mef(); TenantsConfiguration.Initialize(); |

Here’s an updated TenantsConfiguration class:

Code Sample 31

public static class TenantsConfiguration { public static String DefaultTenant { get; set; } public static ITenantIdentifierStrategy TenantIdentifierStrategy { get; set; } public static ITenantLocationStrategy TenantLocationStrategy { get; set; } public static void Initialize() { var tenants = GetTenants(); InitializeTenants(tenants); CreateLogFactories(tenants); CreatePerformanceCounters(tenants); } private static void InitializeTenants (IEnumerable<ITenantConfiguration> tenants) { foreach (var tenant in tenants) { tenant.Initialize(); } } private static void CreatePerformanceCounters( IEnumerable<ITenantConfiguration> tenants) { if (PerformanceCounterCategory.Exists("Tenants") == false) { var col = new CounterCreationDataCollection(tenants .Select(t => new CounterCreationData(t.Name, String.Empty, PerformanceCounterType.NumberOfItems32)) .ToArray()); var category = PerformanceCounterCategory .Create("Tenants", "Tenants Performance Counters", PerformanceCounterCategoryType .MultiInstance, col);

foreach (var tenant in tenants) { foreach (var instanceName in tenant.Counters) { using (var pc = new PerformanceCounter( category.CategoryName, tenant.Name, String.Concat(tenant.Name, ":", instanceName), false)) { pc.RawValue = 0; } } } } } } |

By leveraging the ServiceProvider property, we can add our own tenant-specific services. For instance, consider this implementation that registers a private Unity container and adds a couple of services to it:

Code Sample 32

public sealed class XyzNetTenantConfiguration : ITenantConfiguration { private readonly IUnityContainer container = new UnityContainer(); public void Initialize() { this.container.RegisterType<IMyService, MyServiceImpl>(); this.container.RegisterInstance<IMyOtherService>(new MyOtherServiceImpl()); } public IServiceProvider ServiceProvider { get { return this.container; } } //rest goes here } |

Then, we can get the actual services from the current tenant, if they are available:

Code Sample 33

var tenant = TenantsConfiguration.GetCurrentTenant(); var myService = tenant.ServiceProvider.GetService(typeof(IMyService)) as IMyService; |

There’s a small gotcha here: Unity will throw an exception in case there is no registration by the given type. In order to get around this, we can use this nice extension method over IServiceProvider:

Code Sample 34

public static class ServiceProviderExtensions { public static T GetService<T>(this IServiceProvider serviceProvider) { var service = default(T);

try { service = (T) serviceProvider.GetService(typeof (T)); } catch { }

return service; } } |

As you can see, besides performing a cast, it also returns the default type of the generic parameter (likely null, in the case of interfaces) if no registration exists.

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.