CHAPTER 5

Unlimited Possibilities with Serverless

Serverless is not a technology—it’s a paradigm with these characteristics:

- Abstractions of servers: You don’t need to think about the physical infrastructure that runs your system. Sometimes you can choose certain aspects (for example, Linux or Windows-based OS for Azure Functions), but you have far less control than with IaaS and even PaaS.

- Event-driven, instant scale: Your infrastructure is not fixed but will scale very quickly based on external events, like the number of HTTP calls or pending messages in queue. When there are few requests, the infrastructure will scale down; in some cases, it can also scale to zero when there are no more requests.

- Micro-billing: You only pay for the transactions that you’re doing in the system (depending on the service, it can be the number of executions, memory used, and so on), and not for the underlying infrastructure.

Note: Many serverless services can also be billed as PaaS services; Azure Functions and API Management are examples of services that can be charged with a consumption plan or with fixed plans (like the App Service). You can choose the best mode depending on your workload. If your workload is random, unpredictable, and has high spikes, but also long periods with zero activity, the consumption (serverless) plan is the best candidate. If the workload is fixed, changes slowly, and never goes to zero, fixed plans (with autoscale if available) are better suited. Having the choice means that you don’t have to rearchitect your application if your workload changes over time.

In Azure, the most important serverless services are:

- Azure Functions: Stateless, event-driven execution of code. With Durable Functions, you have a stateful orchestrator for your functions that can also be used to create workflows.

- Logic Apps: Graphical workflow engine with hundreds of out-of-the-box connectors for essential SaaS systems in the market.

- Event Grid: Massively scalable event handler, built for the serverless world. We’ll see how Event Grid compares with other messaging and dispatching systems in the next chapter.

Other PaaS services are being “extended” to support serverless consumption plans, like API Management and the SQL Database compute engine.

Azure Functions

One of the first use cases for serverless computing was to execute small pieces of code in the cloud in a way that could scale indefinitely based on load.

Azure Functions is the Microsoft implementation of this use case, where small pieces of code, called functions, are packaged together inside function apps that can run in a consumption plan (see later in the chapter).

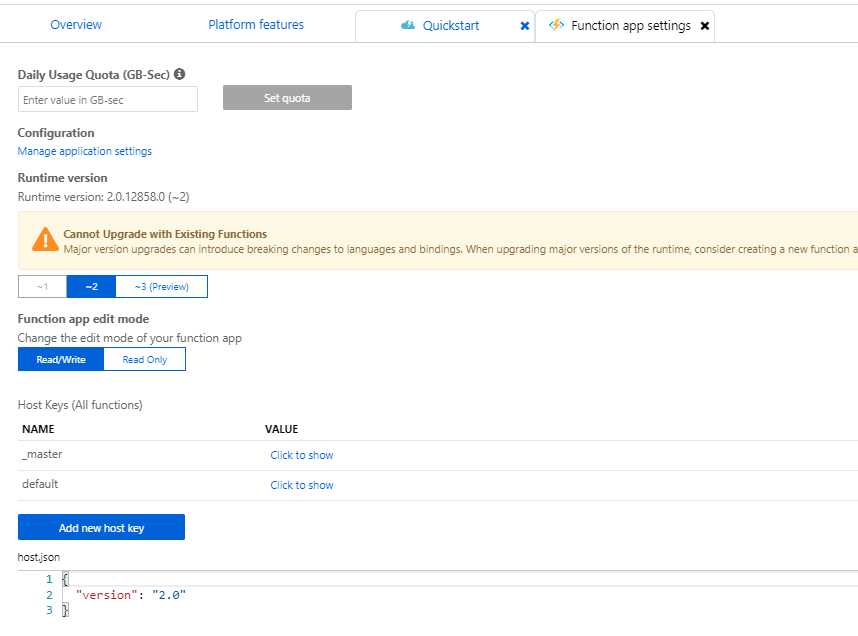

In this book, we will use Azure Functions version 2, since version 1 is in maintenance mode, and version 3 (which includes support for .NET Core 3.0) was in early preview when this e-book was written. You can find more details about the different versions here.

Function apps

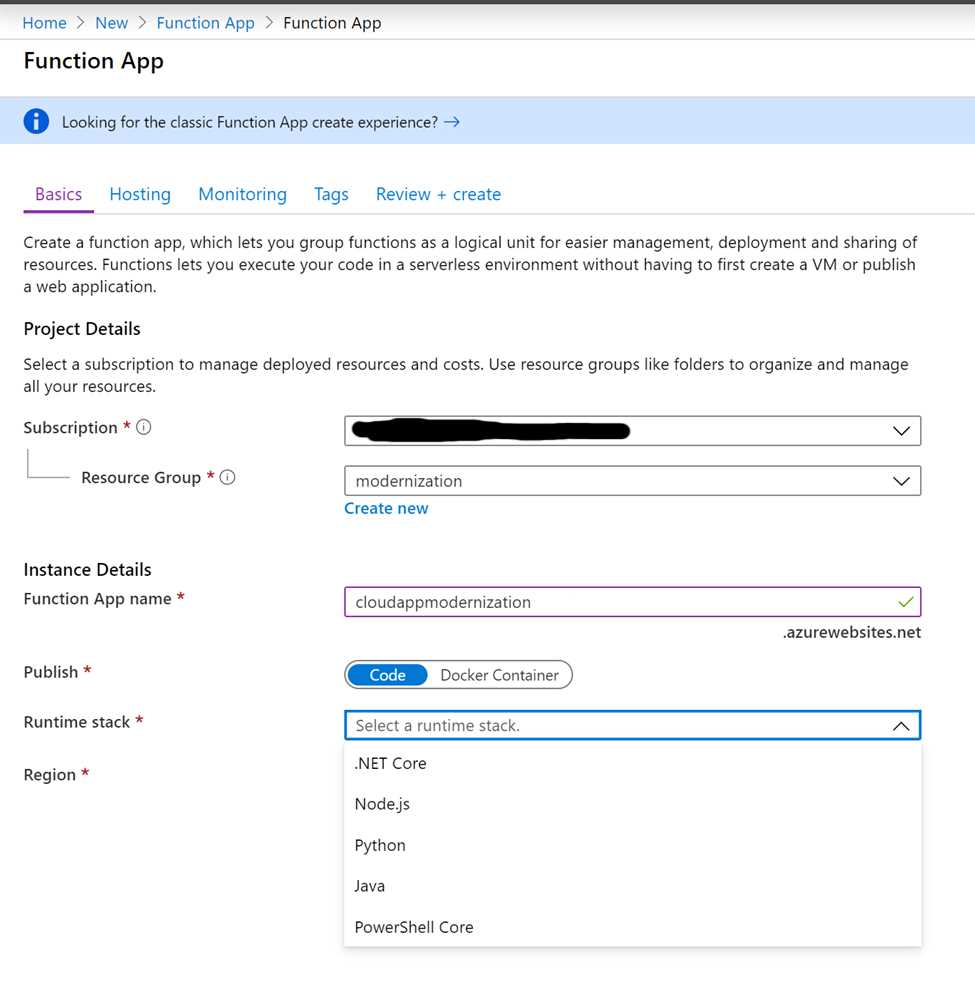

Function apps in Azure Functions v2 (and v3) define many characteristics of the included Azure functions (more details later in the chapter):

- Runtime stack: Every Azure function inside a function app should be written using the same runtime stack, established when the function app was created.

- Operating system: Every Azure function inside a function app should run on the same OS. If you need some functions running on Windows and some functions running on Linux, you should create (at least) two function apps.

- Execution plan: Every Azure function inside a function app shares the same execution plan.

Function apps can also run containers directly, but only when hosted on Linux at this time.

Runtime stacks

Azure Functions v2 supports many runtime stacks:

- .NET Core: C# class libraries, C# script (.csx files), F# (using a precompiled F# class library project only).

- JavaScript: Node 8 and 10 are currently supported. It’s also possible to use TypeScript through transpiling to JavaScript.

- Java: Java 8 is currently supported on Windows hosts. Other JVM-based languages could also run, but are not officially supported (such as Kotlin).

- Python: Python 3.6 is currently supported on Linux hosts.

- PowerShell: PowerShell Core 6 is currently supported on Windows hosts.

Creating a function app

Creating a function app is straightforward, as you can see from the following figures.

Figure 40: Creating a function app—step 1

Every function app should have a unique name (that defines the URL, as in the App Service) and be able run in a region. If you need your Azure functions running in multiple regions, you can create different function apps and use a service like Azure Front Door to route the traffic between them.

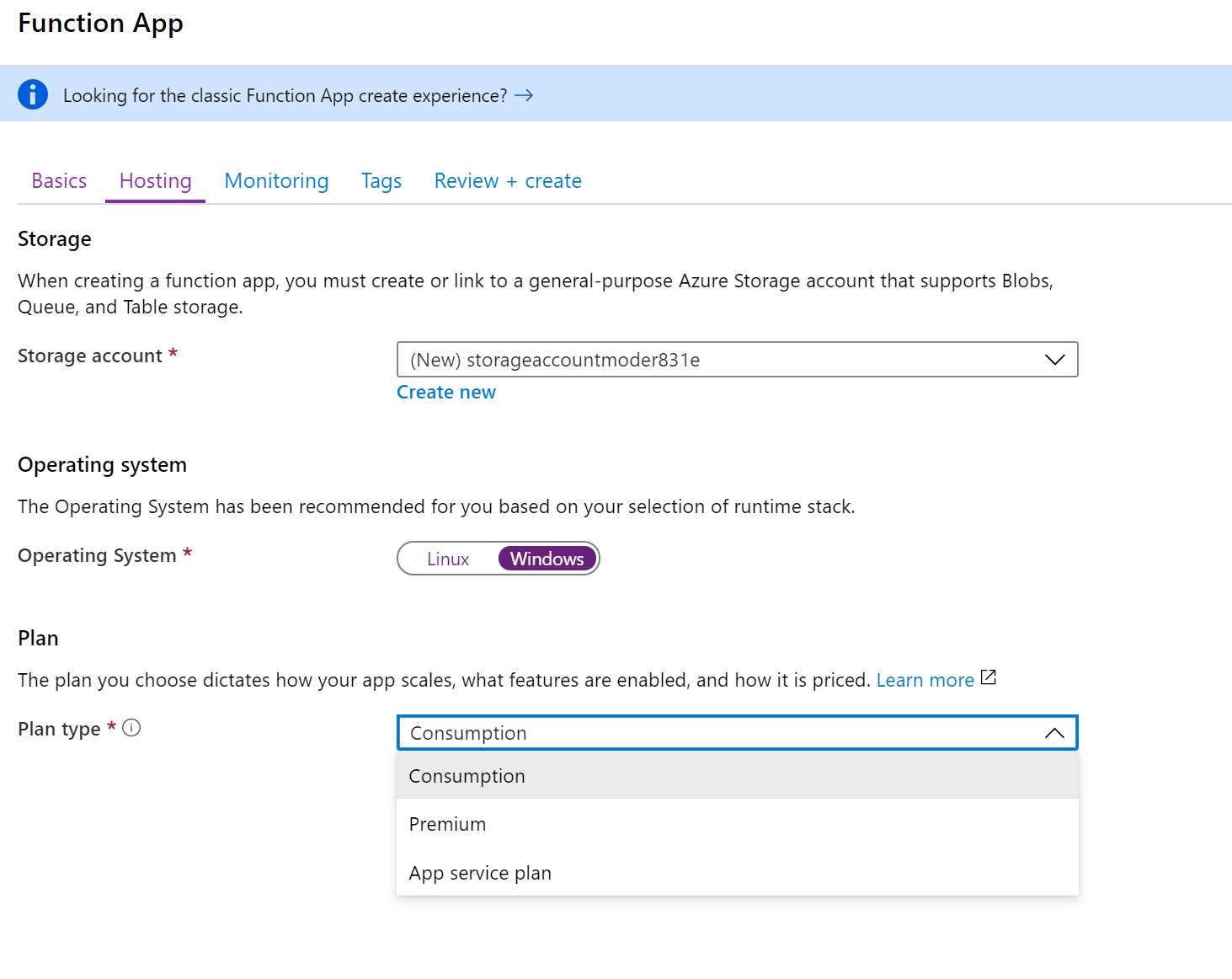

Figure 41: Creating a function app—step 2

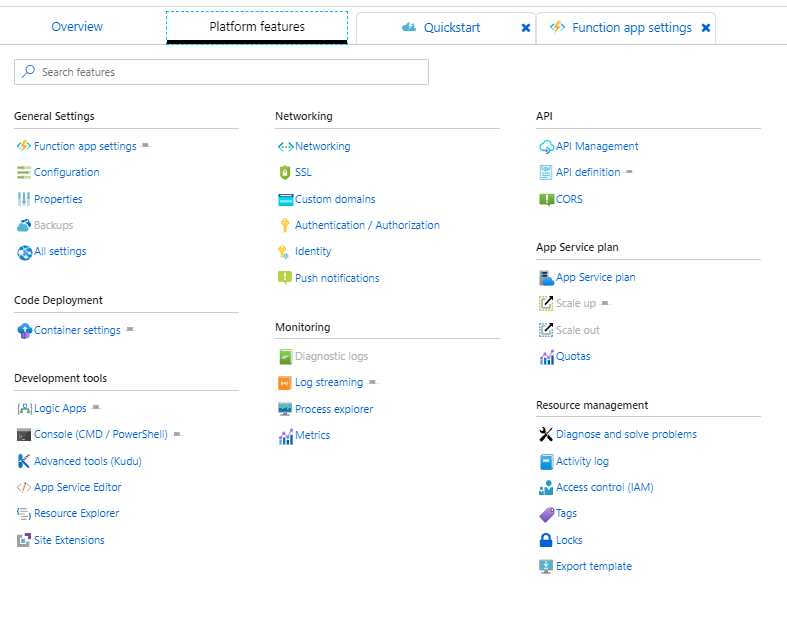

Creating an Azure function

Once a function app is completed, it’s possible to configure its platform features. Most of the features that can be configured are the same as an App Service; some of them are not available when using the consumption plan and are available only when using the App Service plan or premium plan (more on this later in the chapter).

Figure 42: Function app platform features configuration

Function apps also have specific settings that can be configured, including the runtime version, a daily usage quota, the edit mode (read/write when editing .csx files in the portal, read-only for all the other configurations), host keys for security, and more.

Figure 43: Function app settings

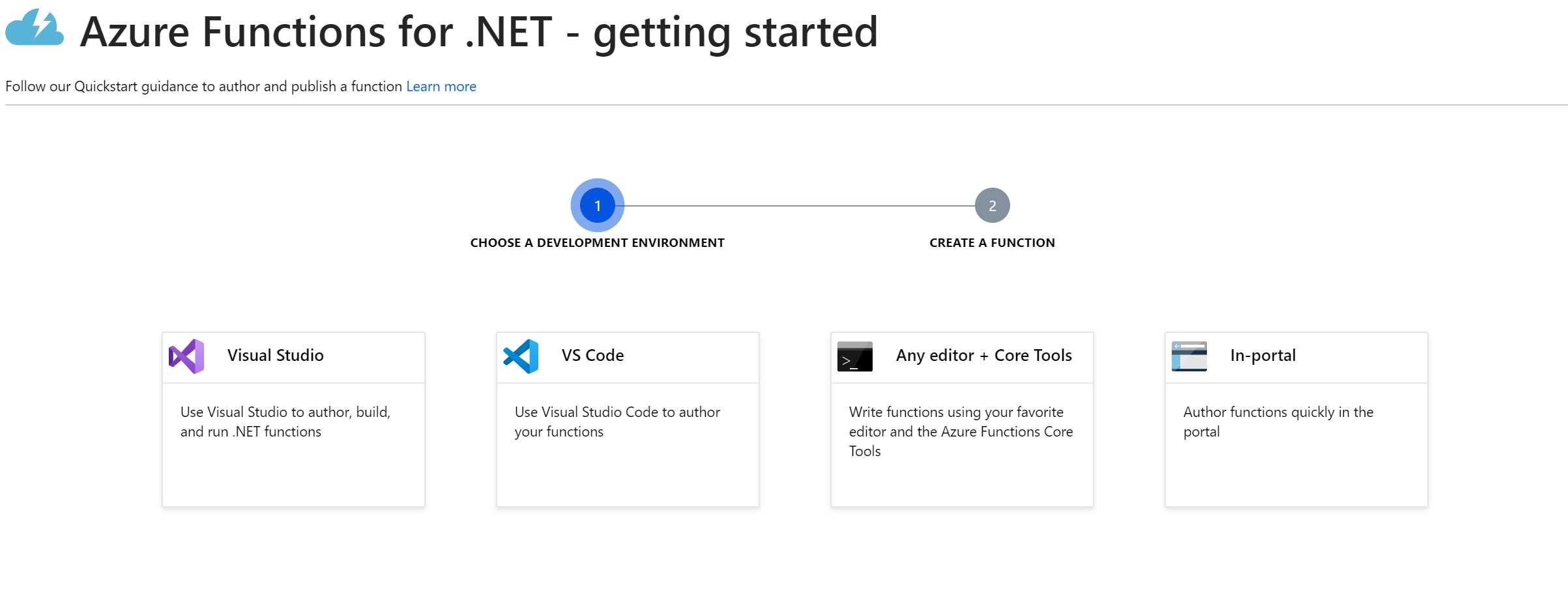

When you create a new Azure function inside a function app, there are different options available, depending on the selected runtime stack. For .NET Core, you can create a new function using Visual Studio, Visual Studio Code, the command line, or in-portal.

Figure 44: Different options to create an Azure function in .NET Core

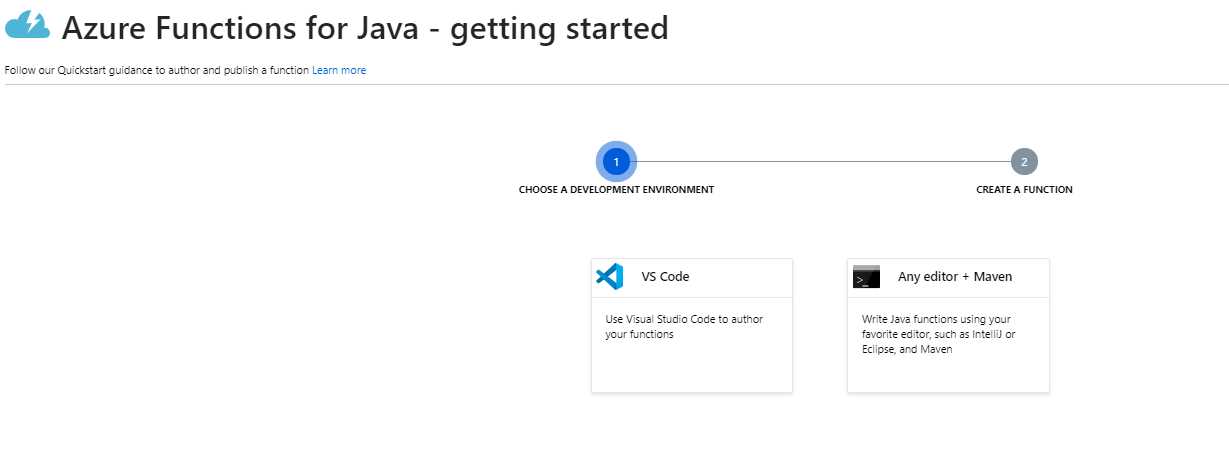

Other runtime stacks have different options. For example, in Java, you can only use Visual Studio Code or the command line (plus Maven, a Java build tool).

Figure 45: Different options to create an Azure function in Java

Our first Azure function

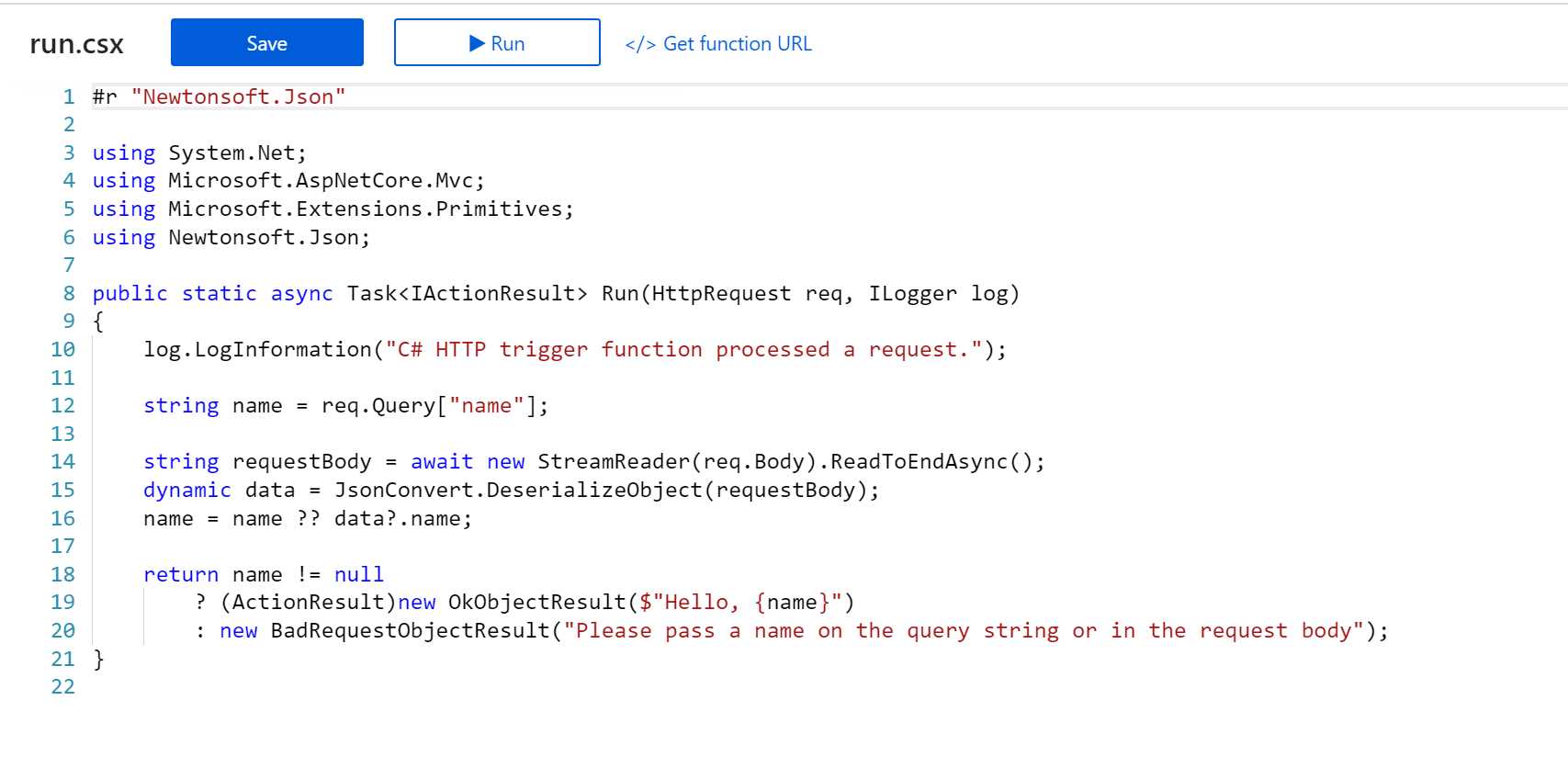

In the following example, we created a new .NET Core-based Azure function in C# script, using the in-portal option of the wizard and selecting an HTTP trigger (that can also be called as a WebHook).

Figure 46: A sample .NET Core Azure function using the HttpTrigger

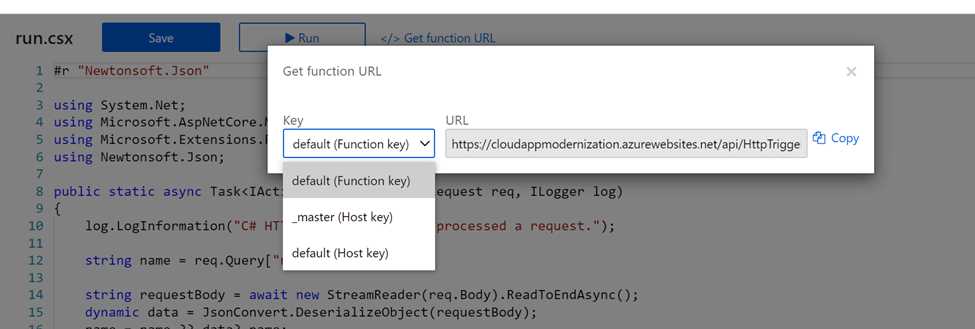

Once the function is created, it’s possible to invoke it from an application or (in this case, since it’s callable with HTTP) from the browser, by obtaining the function URL:

Figure 47: How to get the function URL

Using a key in the URL is the simplest security mechanism supported by the Azure functions, but other authentication/authorization schemes can also be used.

![]()

Figure 48: Calling the function from the browser

Triggers and bindings

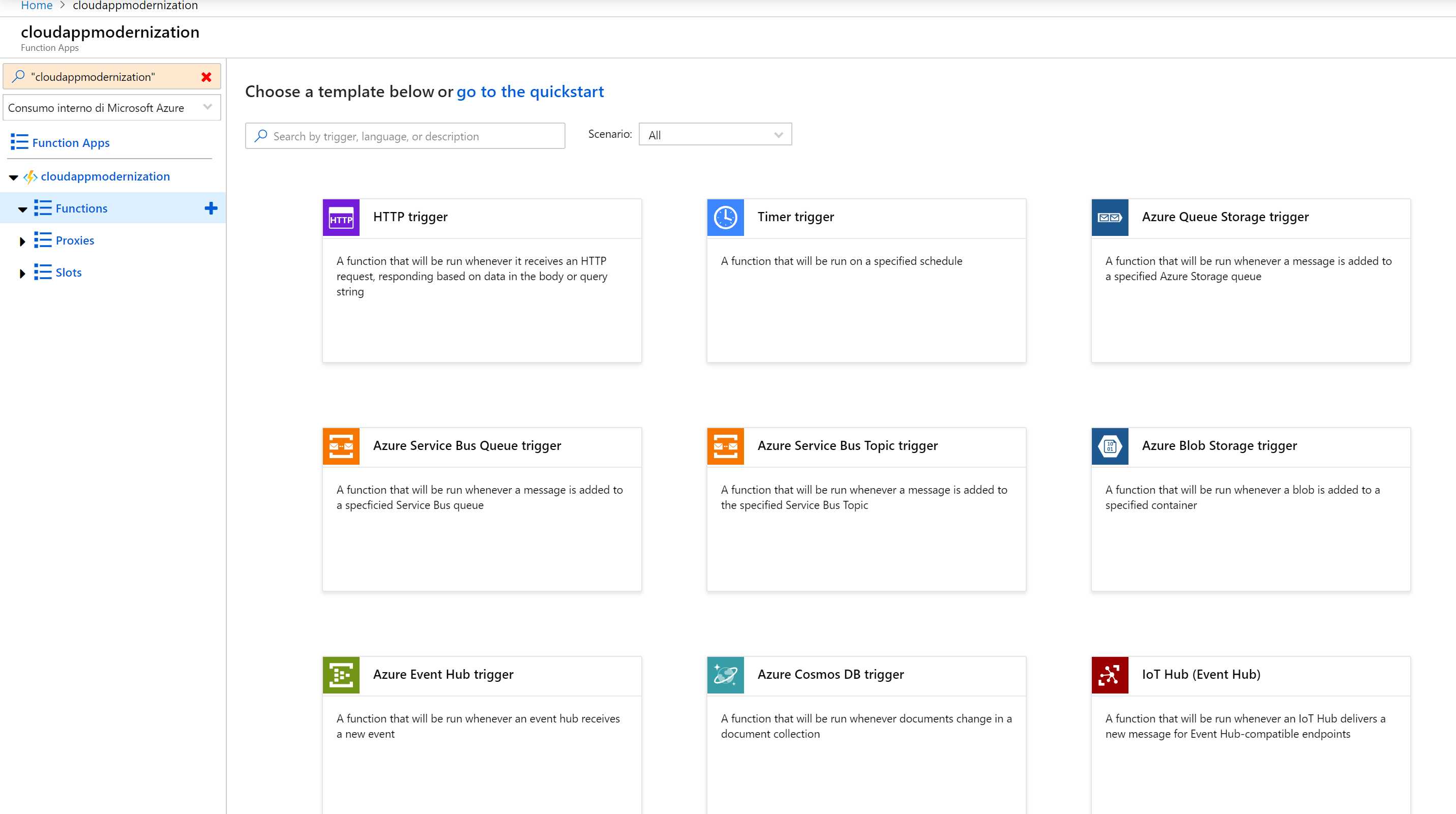

In the previous example, we saw a simple Azure function using the HTTP trigger that allows the invoking of a function with the HTTP protocol.

Triggers decide when and how a function can run. Azure functions natively support a timer trigger that is useful for maintenance tasks. With the timer trigger, you can specify a CRON expression to define at which time the function should run.

There are many other triggers included in the platform: Blob Storage, Cosmos DB, Microsoft Graph, Event Grid, Event Hub, IoT Hub, queue storage, Service Bus, SignalR, etc.

Bindings provide a way to pass parameters to a function (input bindings) or send the output to an external system (output bindings). In principle, bindings are optional, and a function can have multiple input and output bindings.

More information on triggers and bindings can be found here. It’s possible to create custom triggers and bindings, and all the triggers and bindings (apart from HTTP and timer) must be registered in the function app.

Apart from the triggers and bindings provided by Microsoft, you can find hundreds of solutions here.

Figure 49: Creating a function app in the Azure Portal using a predefined template

Azure Functions core tools

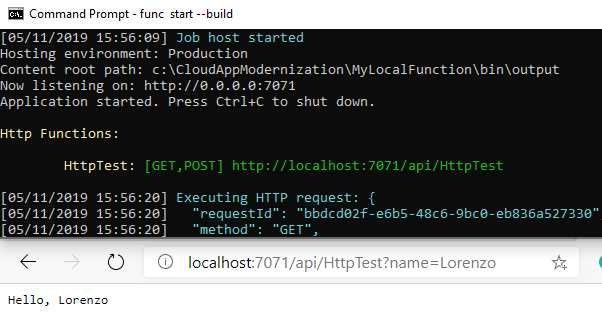

One of the great advantages of Azure Functions over its competitors is the ability to run locally on Windows, Linux, or macOS through the Azure Functions Core Tools.

Once installed, you can test them by opening a CLI in an empty directory and using the following commands.

func init MyLocalFunction

func new

func start –build

The first command will create the function app project using the runtime stack that you want; the second one will create a new function with the trigger that you select; and the third one will start the function (the -build parameter is necessary for .NET Core-based functions).

If you’ve selected an HTTP trigger-based function, the func start command will display the URL of the function that you can test.

Figure 50: Testing an Azure function running locally

When the function is ready, it can be published to Azure directly or by using a Docker container (we’ll cover more on this later in the chapter).

Differences between the consumption and App Service plans

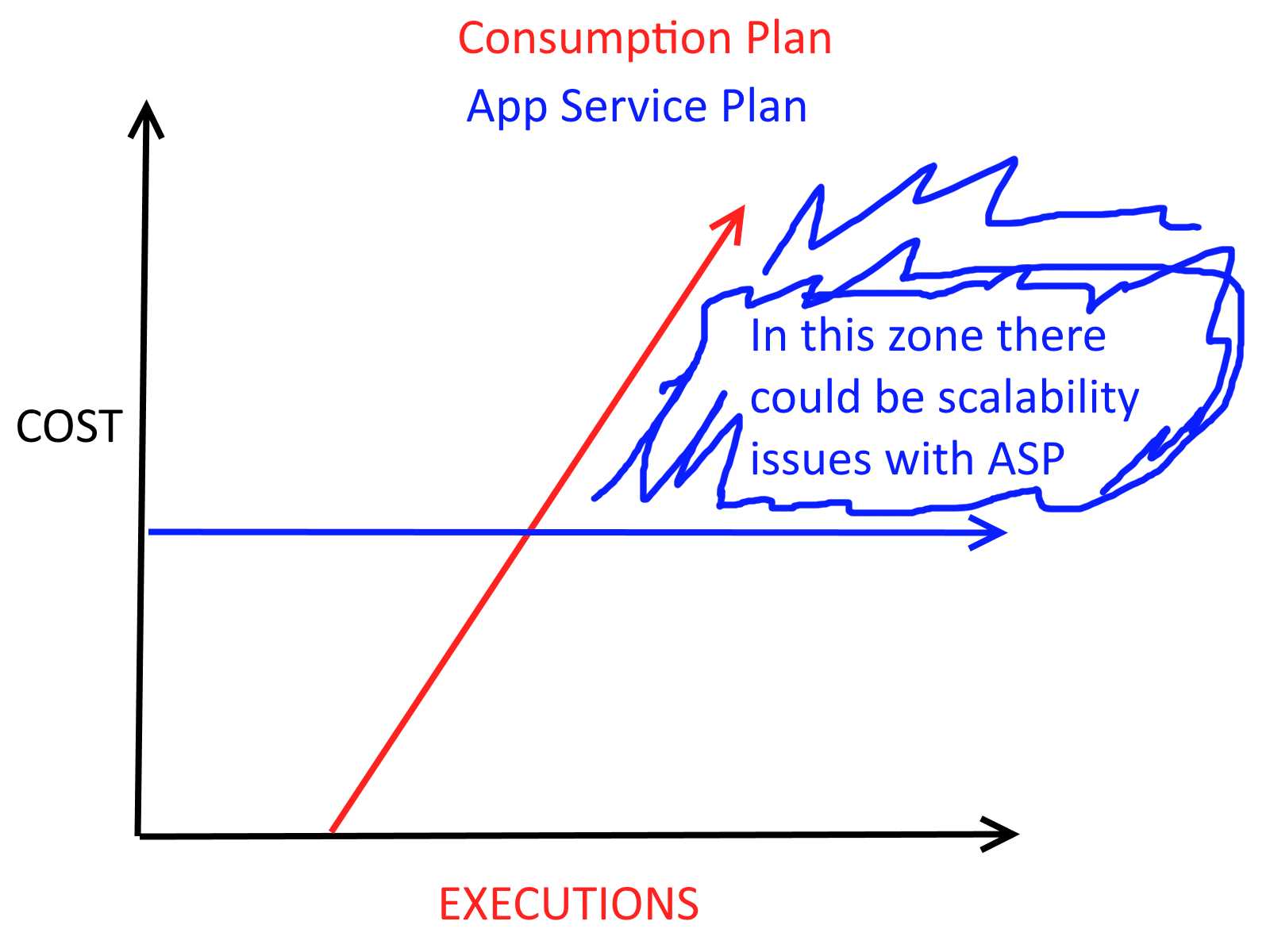

The Azure Functions consumption plan is the serverless plan that is billed based on the number of executions and on the memory used by the function apps over time. The consumption plan can automatically scale based on load and heavy traffic, and you only pay if the functions are used. The consumption plan includes a monthly free grant on both number of executions and memory.

The costs associated with the consumption plan are listed here.

Azure Functions can also run on an App Service plan (using a fixed set of underlying VMs). In this case, the price is fixed, and you also pay when there isn’t a load.

Figure 51: Simplified diagram about cost based on executions on different plans

Looking at the simplified diagram in Figure 52, it seems that the App Service plan is always the wrong choice. When there are no or few executions, you pay more. When there is a big load, you can have scalability problems. Of course, you can autoscale the App Service plan using Azure Monitor.

There are three main advantages of the App Service plan over the consumption plan:

- The price is fixed (if autoscale is disabled) or easily computable (with autoscale), and some customers may like it more than a pure consumption plan.

- The consumption plan can have a cold start problem when it’s scaled to zero because it takes time to start up the function app.

- The App Service plan has many technical advantages. Since you have a set of dedicated machines so that you can attach Visual Studio to live-debug your functions, you can have VNET integration, and many other features of the App Service plan that are not available on a consumption plan.

The consumption plan can scale very fast (queues are evaluated in seconds), while the App Service plan autoscale can run every five minutes, leaving a big space in case of quickly changing loads.

Functions premium plan

The functions premium plan was introduced to overcome the limitations of both the consumption and App Service plans.

With the functions premium plan, you always have prewarmed instances (so it cannot be scaled to zero, and you still pay for those instances when there’s no load), you have all the features of App Service plan (such as Visual Studio debugging and VNET integration), but the scaling follows the same rules of the consumption plan (with limits that you decide; it’s not unlimited), so it’s much faster than the App Service plan.

To better understand the differences among the three plans, see this article.

Linux-based functions and containers

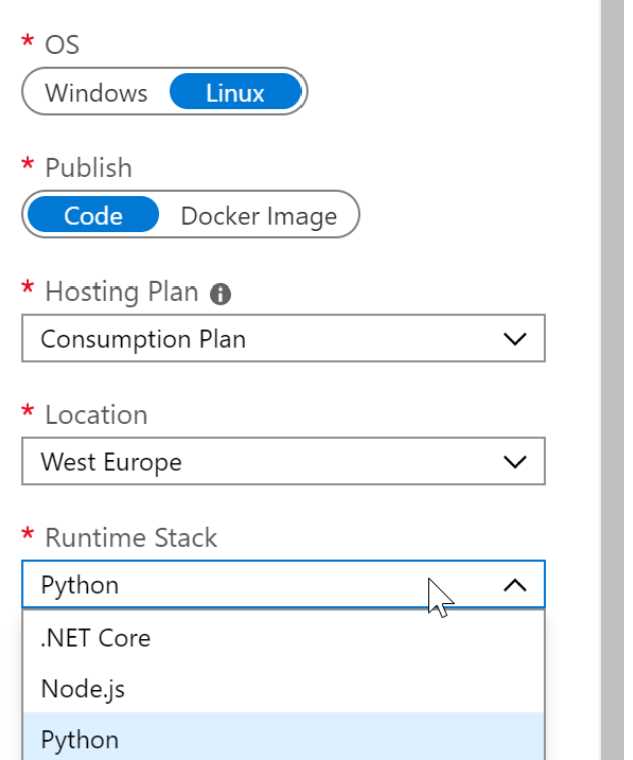

Since the release of Azure Functions 2.0, you can decide to host your functions on Linux instead of Windows.

Figure 52: Creating a Linux-based function app

If you choose Linux, your functions will run inside containers instead of a web app (since Azure functions are based on App Services, this is a similar working model).

If you choose to deploy code inside your function app, you end up using a Microsoft-managed container that can run .NET Core, Node.js, or Python. Your code is then published on top of the container, and it will run from there. You can create the Linux-based function app in the portal, or by using Azure CLI.

You can also choose to use a custom Docker image, stored on Docker Hub, Azure Container Registry, or wherever you want, and run your functions from there. You usually decide to create a custom container if the platform that you need is not supported, or if the version that you need is not supported. In this case, you should create your custom image, starting from one of the base containers, and publish it.

Running (Linux-based) Azure functions on Kubernetes everywhere

Azure functions running inside containers can be hosted wherever a container is supported. You can run them on Azure container instances, on a VM with Docker installed, or on Kubernetes (AKS, on-premises, or on other cloud providers).

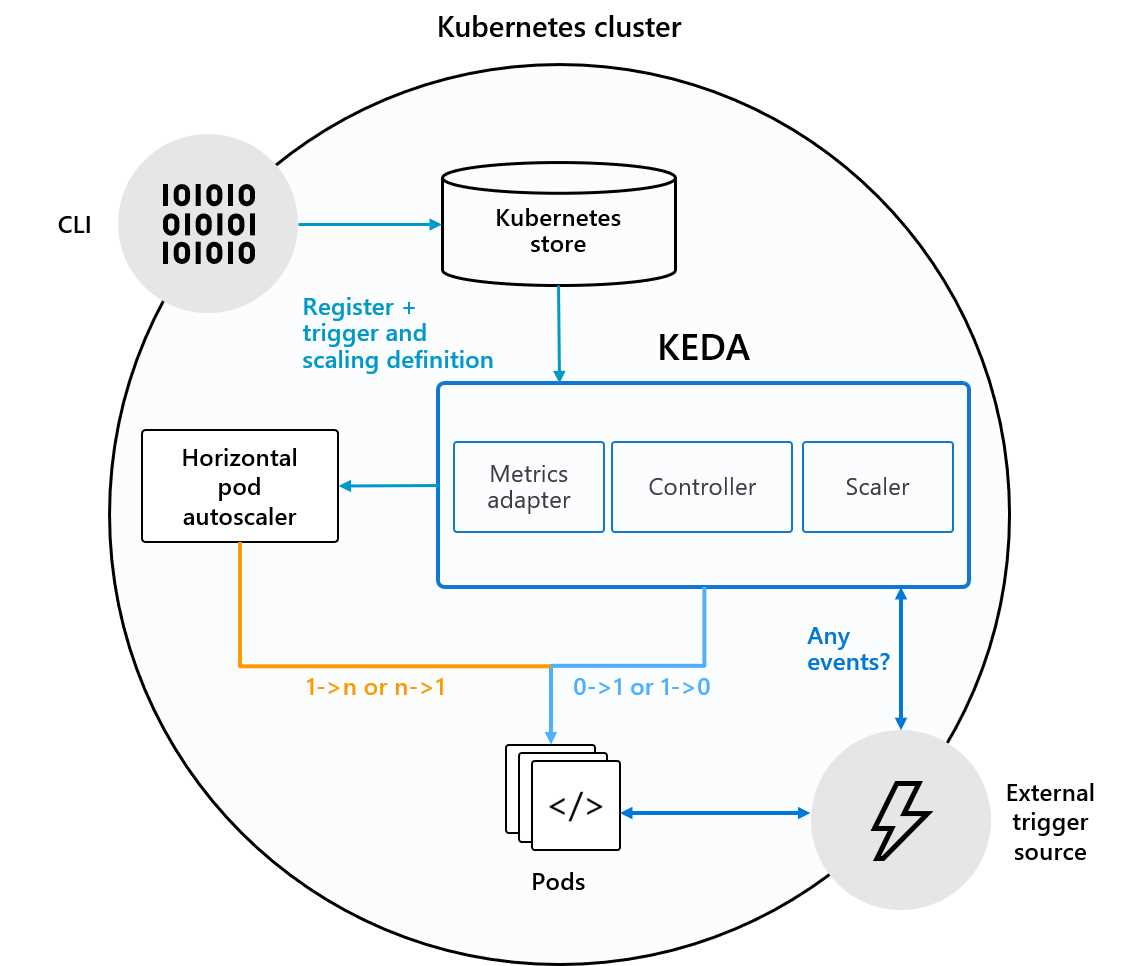

If you run Azure functions on Kubernetes, you should take a look at KEDA (Kubernetes-based event-driven autoscaling), which allows your orchestrator to scale nodes based on external sources and not only the internal parameters of the cluster.

KEDA is an open-source project created by Microsoft and RedHat. It can run on-premises and in the cloud (on every cloud), and can be integrated into vanilla Kubernetes or AKS, OpenShift, and so on. With KEDA, for example, you can scale your resources based on the HTTP queue, and you can also scale your resources (pods) to zero.

Figure 53: KEDA integration with Kubernetes (from GitHub documentation)

Apart from HTTP queues, KEDA enables pod autoscaling based on:

- AWS CloudWatch

- AWS Simple Queue Service

- Azure Event Hub

- Azure Service Bus Queues and Topics

- Azure Storage Queues

- GCP PubSub

- Kafka

- Liiklus

- Prometheus

- RabbitMQ

- Redis Lists

You can find more information about KEDA here, or on the official GitHub page.

Durable Functions

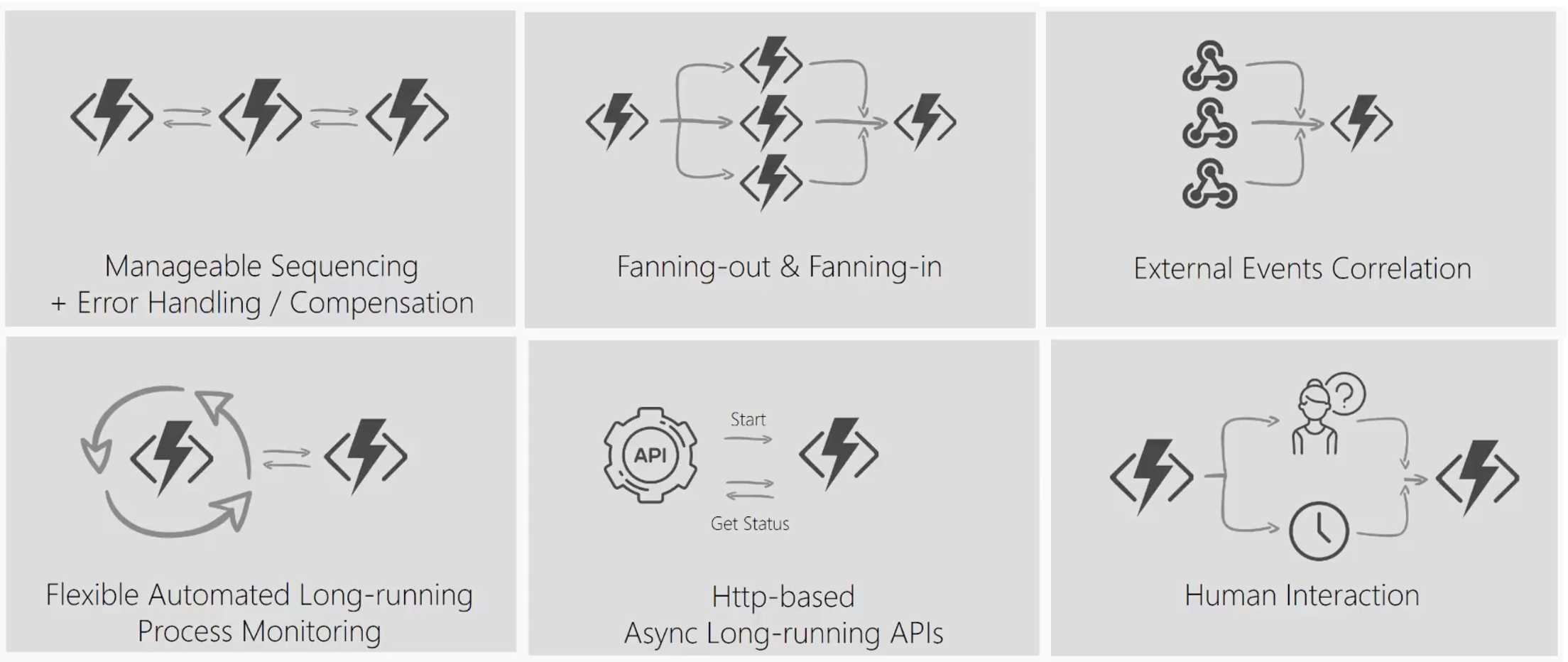

Durable Functions can be used to implement patterns that are difficult with stateless Azure functions.

Figure 54: Patterns that are suited for durable functions (from a Microsoft presentation)

You can create Durable Functions in C#, F#, and JavaScript, and they are entirely code-based. Durable Functions are technically extensions of Azure Functions that can run orchestrator functions (for workflows) or entity functions (for stateful entities).

Durable Functions billing is based on Azure Functions (consumption, app plan, or premium functions plan), but with some differences that are explained here.

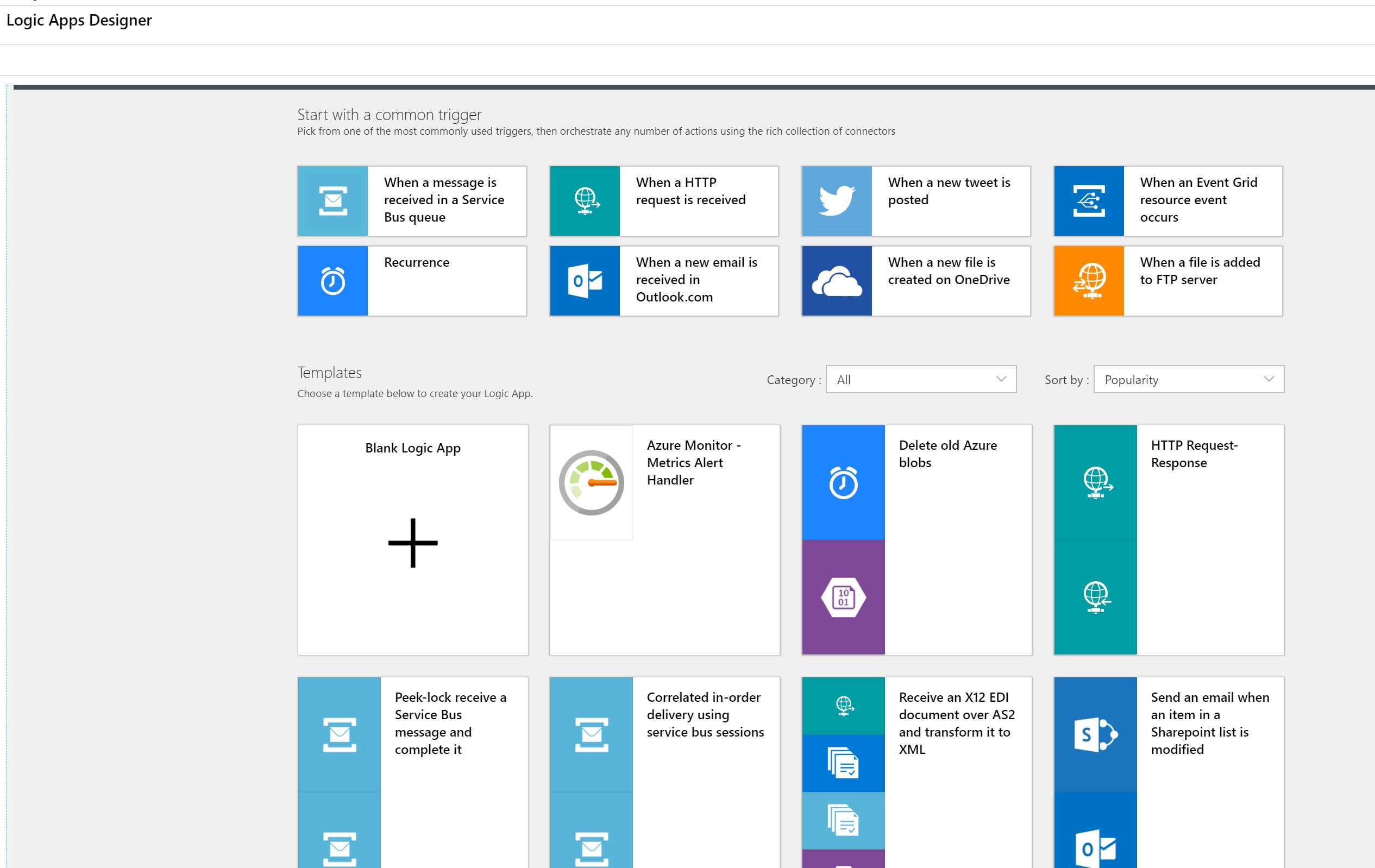

Logic Apps

Azure Logic Apps is a service used to create tasks, business processes, and workflows that integrate data, systems, or services inside an organization or across organizations. Logic apps can run based on an event that can be a timer, an HTTP call, a change in a database, blob storage, or an event in a third-party system like Office 365, Salesforce, Teams, Slack, OneDrive, Outlook.com, Oracle, Dynamics, or SAP.

Note: Logic Apps can be used to modernize BizTalk Server Apps with the use of Enterprise Integration Pack. You can also have mixed scenarios.

Figure 55: Logic Apps creation wizard

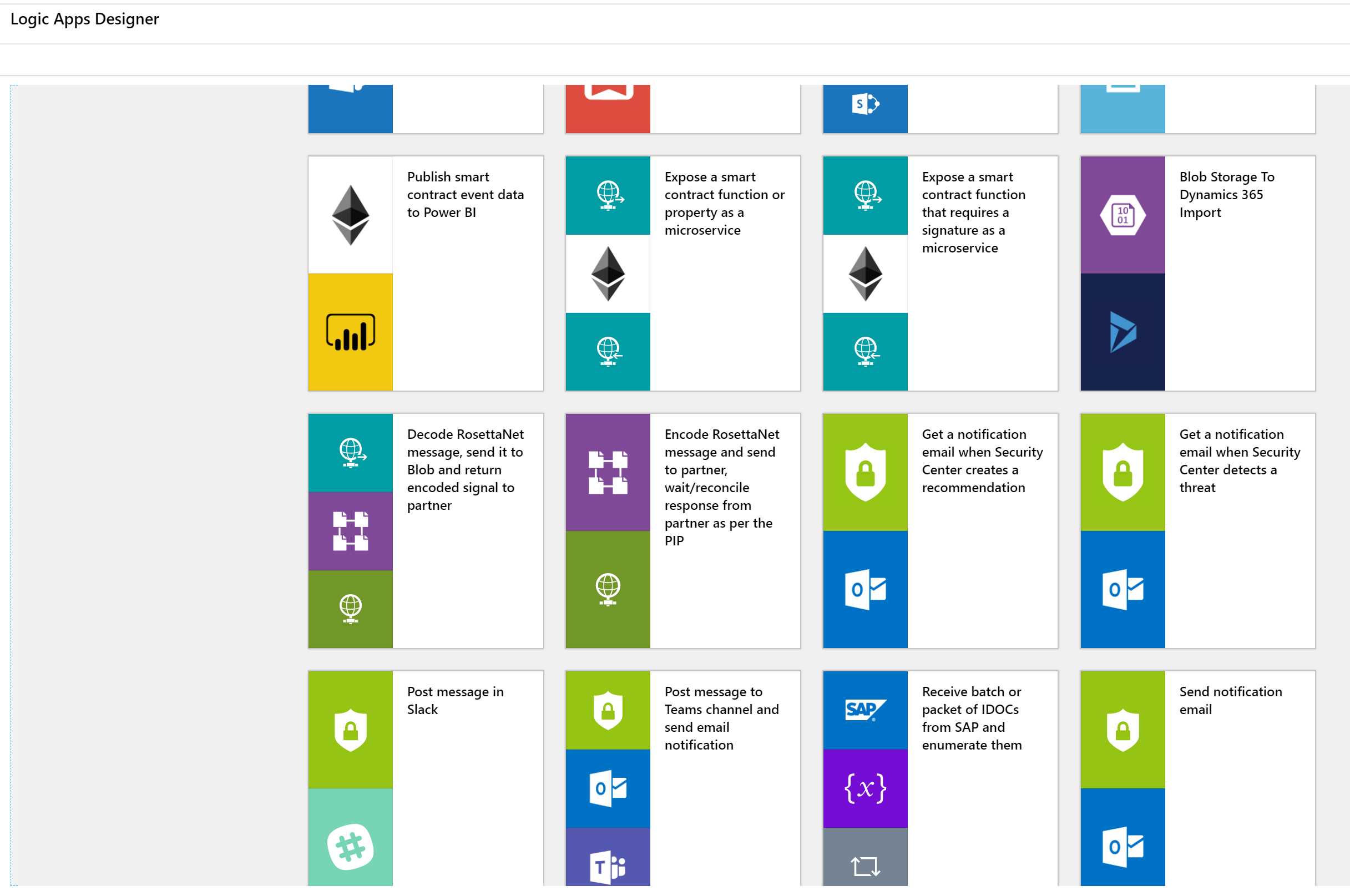

There are hundreds of connectors and integrations already built and you can create your own connectors.

Figure 56: Other default Logic Apps templates

Once you have chosen a template, you can set up authentication to the various services, and then you can customize every step or introduce new steps, conditions, parallel paths, and so on.

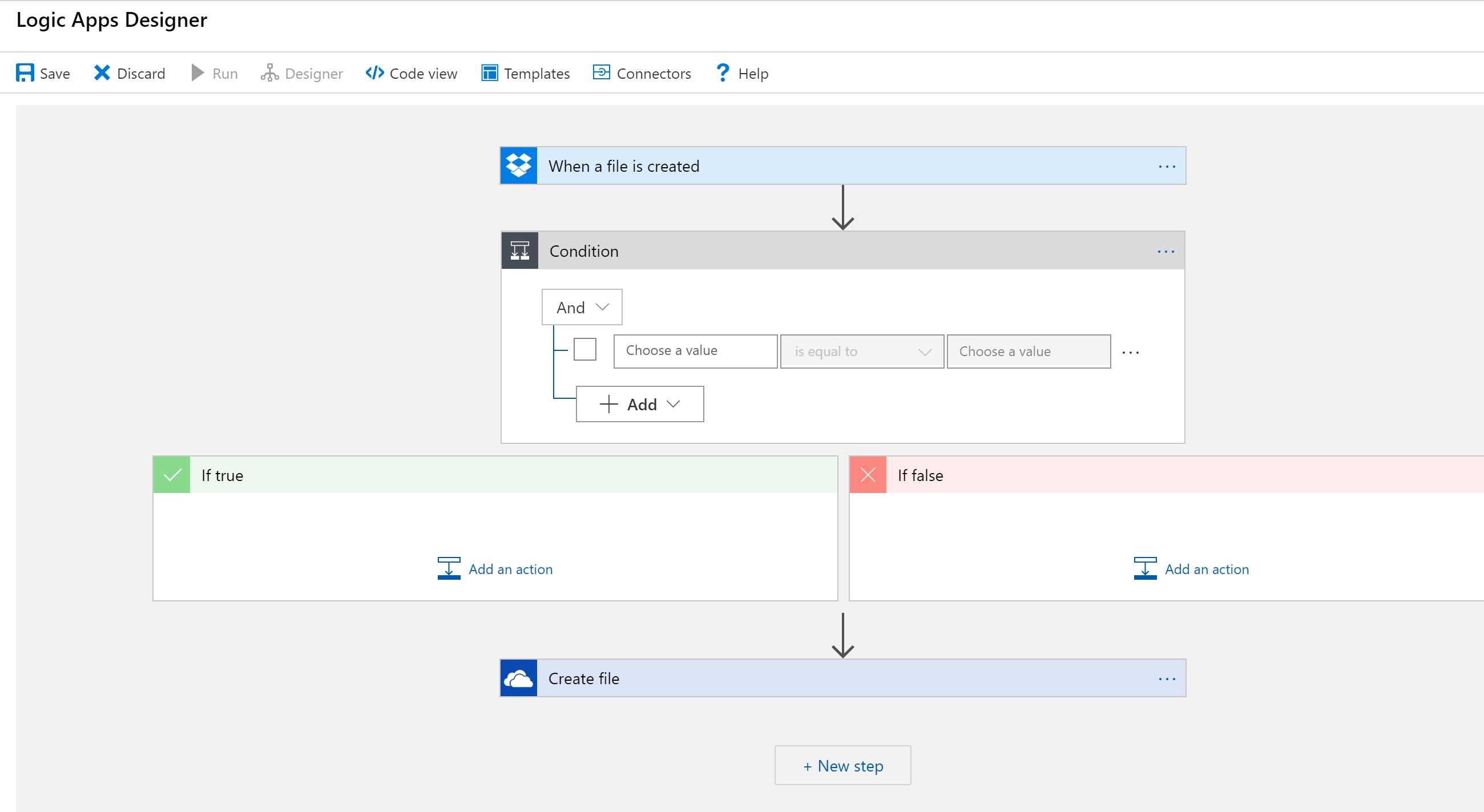

Figure 57: Logic Apps Designer workflow

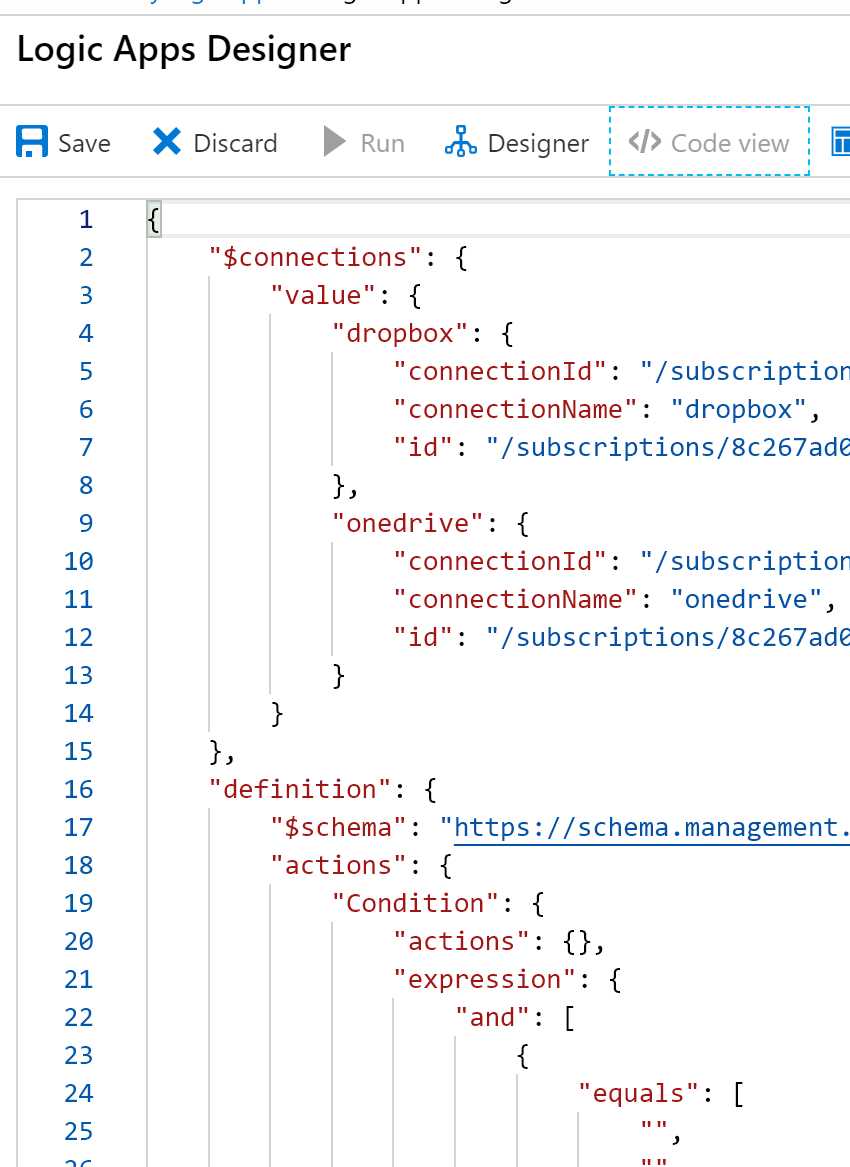

Of course, you’re not limited to the visual designer. You can view (and even create) the workflow using the underlying ARM template, and you can automate it with Azure DevOps or other tools.

Figure 58: Logics Apps Designer code view

The Logic Apps pricing model is based on the number of actions (triggers, connectors, conditions, etc.) that are executed over time.

Note: If you need to access secure resources inside a VNET, or you need more isolation, increased duration, throughput, message size, etc., you can use Integration Service Environments (ISE), which are Logic Apps running in an isolated instance. Prices and limits are different than normal Logic Apps. ISE is not priced with a consumption plan.

When to use Durable Functions vs. Logic Apps (vs. Power Automate)

Durable Functions and Logic Apps can be used to obtain the same results and run orchestration processes. The main difference is that Durable Functions are code-first, and Logic Apps are designer-first. With Durable Functions, you have a limited set of triggers and bindings; you need to use products’ SDK to integrate different services, while Logic Apps have a vast collection of connectors. You can find more information here.

Power Automate (previously known as Microsoft Flow) is an integration service that Microsoft has created for Office workers, business users, and SharePoint administrators. Power Automate is built on top of Azure Logic Apps, and they use the same connectors. The main difference is the pricing model and the intended audiences. You can find information here.

Note: It’s also possible to export flows from Power Automate to Logic Apps.

Microservices and serverless

There are many ways to implement microservices; we have seen in the previous chapter that containers and orchestrators (Kubernetes) are one of the most popular, but certainly not the only option.

For some kinds of microservices, using a serverless approach can be easier and faster to implement. Typical problems with microservices implemented with containers are:

- Scaling of compute resources (KEDA can be an option to mitigate the problem).

- Operations management.

- Pay-per-hosting nodes.

- Services discovery and managing services integration.

With serverless, most of the problems are easy to solve:

- Automatic scaling based on workload.

- No infrastructure management.

- Pay per execution.

- Event-based programming model (triggers and bindings).

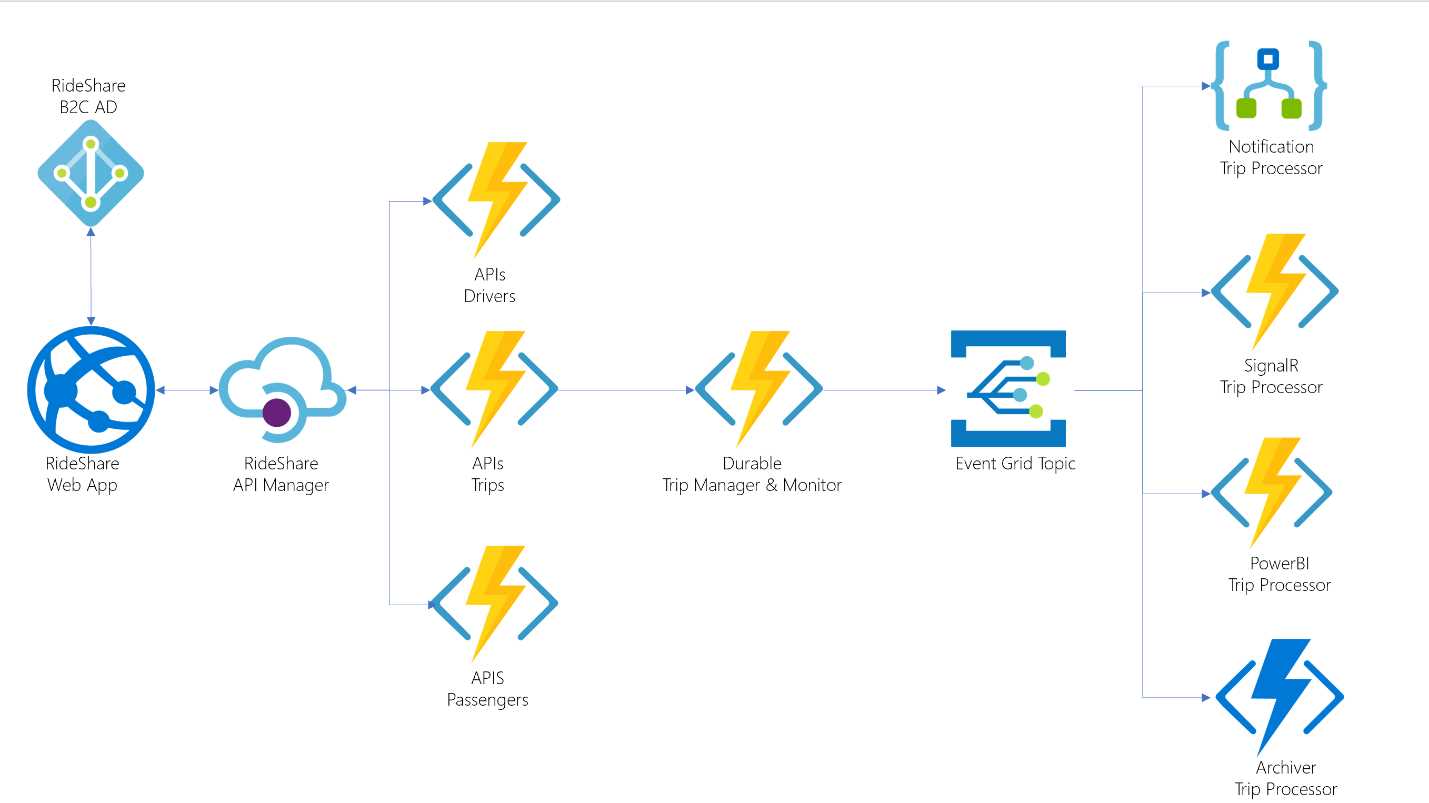

You can find a reference implementation of a microservices architecture (to implement a simple, Uber-like service) using Azure Functions (including Durable Functions), Logic Apps, Event Grid, and API Management here.

Figure 59: Relecloud reference architecture (from GitHub)

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.