CHAPTER 8

Searching and Relevance

Do People Love Searching?

When it comes to searching in Solr (and in general), people love searching for things, right? At least, that's the impression we’re always given; unfortunately, it's really very far from the truth. The truth is this: People love finding what they're looking for.

As a developer of a search application, it's our job to return the results most relevant to a user’s query, and let them fine-tune things from there. While you’ll definitely get brownie points if you magically present the user with the results they want the first time, 99 percent of the time, getting very close is good enough.

Relevance

Relevance is the degree to which a query result satisfies the user who is searching for information. It means returning what the user wants or needs. There are basically two important concepts we need to consider when talking about relevance: precision and recall.

Precision

Precision is the percentage of documents in the result set that are relevant to the initial query. That is, how many of the documents contained the results the user was actually looking for. To be clear, we’re not talking about exact matches here either; if you're looking for "red cars," matches containing "cars" may still be valid, but matches containing "red paint" would not.

Recall

Recall is the percentage of relevant results returned out of all the relevant results in the system. That is, whether the user got all the documents that in reality matched his or her query. Initially, it is a little bit difficult to understand with a definition, but it becomes a lot simpler with an example:

- You have an index with 10 documents.

- You have a specific query that would match four documents.

- When you run this query, you only get two documents. This means that your recall is not that good, as it is only returning half of the documents that it should.

In real life the scenarios are much more complex; search engines have from thousands to millions of documents, so returning the relevant documents can be difficult.

Obtaining perfect recall is trivial. You simply return every document in the collection for every query, right? But this is a problem if you return every document in the collection—it might not be very useful for the user.

And here is where relevancy comes in. Relevancy is the number of the documents returned by the search engine that are really relevant to your query. To use a real life example, imagine you run a query in Google, and the first page does not return any useful results. None of the results are “relevant” to your query.

There are four scenarios that you need to consider:

- True Negatives: These results should never appear in a result set, as they have nothing at all to do with satisfaction of the presented query. A true negative is as bad as it gets for search results; returning them means your search application is not doing its job correctly at all.

- False positives: A false positive is when a query matches something in the database, but that match does not relate to the context of the search. Taking our precision example from the previous section, "red paint" would be a false positive—the match occurred due to the use of the term "red," but the context of "paint" does not relate to a context describing cars.

- False Negatives: As the name suggests, it’s the complete opposite of a false positive. A false negative occurs when a document result matches, but is not returned by the search application. In our previous example, "red car paint" might get rejected on the grounds that its context applies only to paint, and not to a car that's painted red, which is incorrect if our search criteria involves "red cars." When designing your search application, you never want to produce results like this.

- True positives: This is the end game—what you’re aiming for every time. These are true, context-relevant search results that either satisfy the query, or make it easy to see how the query can be re-organized in order to be better.

Accuracy

This leads to accuracy, which is a tradeoff. In some cases, if you get high precision, you might get very little recall. That is, you might get documents that are extremely relevant to your query, but you might get very few of them. This ultimately results in missing documents that potentially include relevant, but less precise, information for the end user.

At the other end of the spectrum, we have large recall, but with much lower precision. The trick to getting accuracy right is getting the correct balance between these two ends.

Not All Results Are Created Equal

Finally, it is very important to understand that not all results are created equal. When you are configuring your search engine, you need to consider your user’s needs.

Context

You need to take into account the categories for each one of the contexts. For example, say you are doing a search for a development company, and you have IT pros and developers. The IT pros might like to get results that are more related to servers and network technologies, while developers might want to look into web development—yet they might be using the same keywords.

Second Page?

It is also important to consider the relevance of the documents. Users rarely go beyond the second page of results, meaning the most relevant results need to be on the first page, with the second page containing the not-so relevant results.

Document Age

In some cases, document age is incredibly important. For example, if you were searching for current news in a newspaper, you only want the most up-to-date results.

Security

A lot of search engineers never give this a second thought, but security is hugely important. I worked on a project for Microsoft a number of years ago where, as part of a security initiative, we had to perform an analysis of approximately 300,000 SharePoint sites. The goal here was to find and prevent unintentional access to confidential company information that the search engine may have returned by mistake. Document security must always be a number one priority.

Speed

Finally, we get to the issue of speed, and the bottom line is this: people expect search results pretty much instantly. A few milliseconds, or maybe even one second, is tolerable for most people. Beyond that, you’re going to see complaints—lots of them.

I’ve seen exceptions where queries could take minutes, but this specific process used to take hours to find the relevant information. This is generally a specialist scenario, where minutes are a massive savings of time, in the bigger scheme of things.

Queries, Data, and Metadata

There are billions of search users worldwide, thanks mainly to Google. However, when you search using Google, you are limited to a small subset of keywords, which includes site, link, related, OR, info, cache, +, -, and other similar operators. If you think about it objectively, this is fine; Google crawls the web, which is kind of a “wild west” humongous set of mainly unstructured data, and not a nice, neatly ordered collection that we might be searching if it was our own data.

Data and Metadata Searching

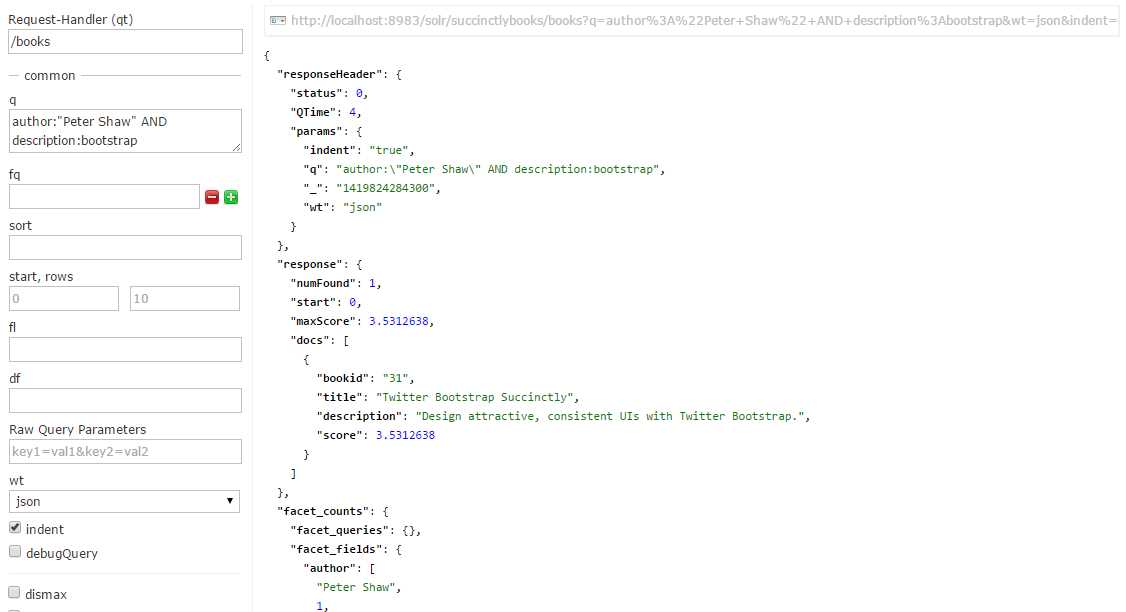

Within Solr we have more control over our data and the metadata that we have in our index. This allows us to be very accurate and define queries that answer very specific questions. Using our Succinctly series data set as an example, we can look for all books by Peter Shaw that talk about Bootstrap.

You would achieve this with the following query:

http://localhost:8983/solr/succinctlybooks/books?q=author%3A%22Peter+Shaw%22+AND+description%3Abootstrap&wt=json&indent=true |

As you can see in the following figure, we get a very precise and exact match to our query, with only one result.

- Precise query by author and description

Going Deeper into Solr Search Relevancy

To really understand search and be skilled in tuning search relevancy, it is important to understand the Lucene scoring algorithm, known as the tf.idf model. tf.idf is an acronym that stands for term frequency, inverse document frequency. The terms are described in the following paragraphs.

tf (Term Frequency)

Term frequency is the frequency in which a term appears in the document or fields. The higher the term frequency, the higher the document score.

idf (Inverse Document Frequency)

The less term appears in other documents in the index, the higher its contribution to the score.

There are two other terms that are not mentioned as part of the name of the scoring algorithm tf idf, but are equally important. The terms are as follows:

coord (Coordination Factor)

The more query terms found in the document, the higher the score.

Fieldnorm (Field Length)

The more words a field contains, the lower its score. It penalizes documents with longer field values.

There are multiple pages in the documentation that talk about Lucene scoring. It's highly recommended that you spend some time reading and understanding them in order to make your search applications return better results.

Query Syntax

The DisMax query parser is the default parser used by Solr. It’s designed to process simple phrases entered by users, and to search for terms across several fields using different weights or boosts. DisMax is designed to be more Google-like, but with the advantage of working with the highly structured data that resides within Solr.

DisMax stands for Maximum Disjunction, and a DisMax query is defined as follows:

A query that generates the union of documents produced by its sub-queries, and that scores each document with the maximum score for that document as produced by any sub-query, plus a tie-breaking increment for any additional matching sub-queries.

That is a bit of a mouthful—just know that the DisMax query parser was designed to be easy to use and to accept input with less chance of an error.

Let’s review some of the possibilities regarding search.

Search for a Word in a Field

Up until now, we’ve been mostly looking for *:* which meant all searchable fields, all values. You can specify what word or phrases you want to look for, and in which field.

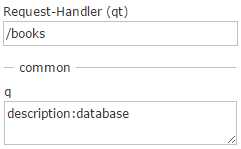

For example, say I want to look for all books that have “database” as part of the description. I would run a query from the Admin UI for description:database using the /books request handler as follows:

- Our example query as it might be viewed using the Admin UI in Solr

The query should give you four results, which you can retrieve to a page of their own using the following URL:

http://localhost:8983/solr/succinctlybooks/books?q=description%3Adatabase&wt=json&indent=true |

There is something you might notice, however: take a close look at the results returned by the URL, specifically at the score that's returned for each.

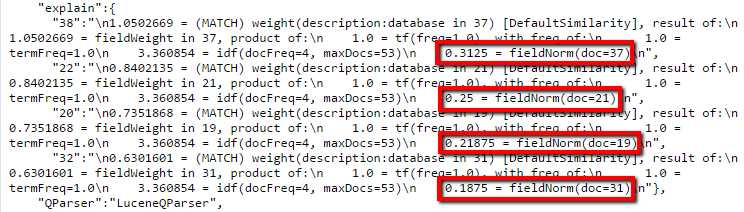

The scores returned range from 1.05 to 0.63, which is fine for a general search using wildcards over several fields, but in our case, we’re searching for a specific word, in a specific field that we know occurs exactly once in each result. Shouldn't the score in this case be equal for each result?

- Different scores for description

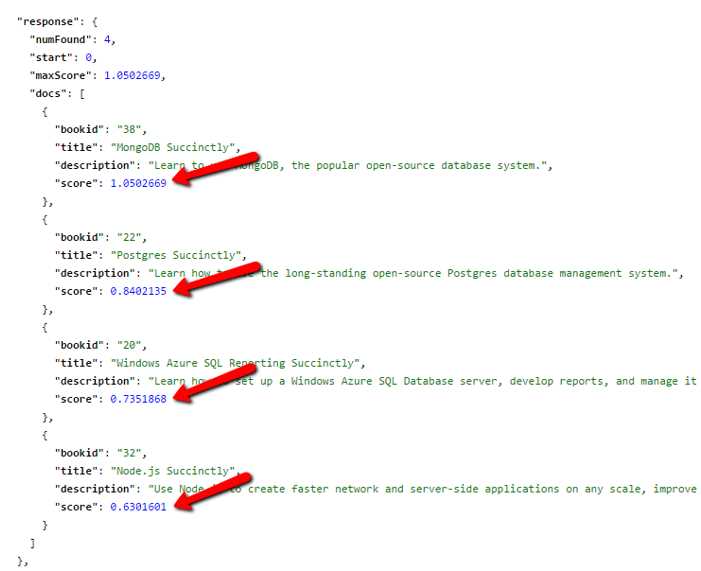

Let's test this on a different field and see what happens. This time, we'll search the authors’ names for occurrences of my name, using author:"Xavier Morera". Enter the following URL into your browser, making sure to adjust where needed for domain name and port number:

This time, we can see that the score for each result is now the same.

- Same score for author field

In order to show you what's happening here, we need to repeat the "database" query, but this time, we'll use the debugQuery option to help us. If you’re running from the Admin UI, make sure you check the box by debugQuery before clicking Execute.

![]()

- debugQuery Checked

If you’re entering the URL directly, make sure you add debugQuery=true to the end of the URL before submitting it to your browser:

http://localhost:8983/solr/succinctlybooks/books?q=description%3Adatabase&wt=json&indent=true&debugQuery=true |

If you scroll down through the results to the debug section, you should see the answer in the "explain" section; the "fieldnorm" process in Solr is the element that makes all the difference.

- Fieldnorm makes a difference

Part of the analysis includes fieldnorm, which penalizes longer fields. If you look at the following figure, you can see I've drawn a red line across the ends of the descriptions, and you can see that the results at the top (With the more specific score) have shorter descriptions.

- Description gets longer as ranking increases

This is just one specific case, where the keyword appeared only once in four documents, and the only difference was the field length. Real-world queries are usually much more complex.

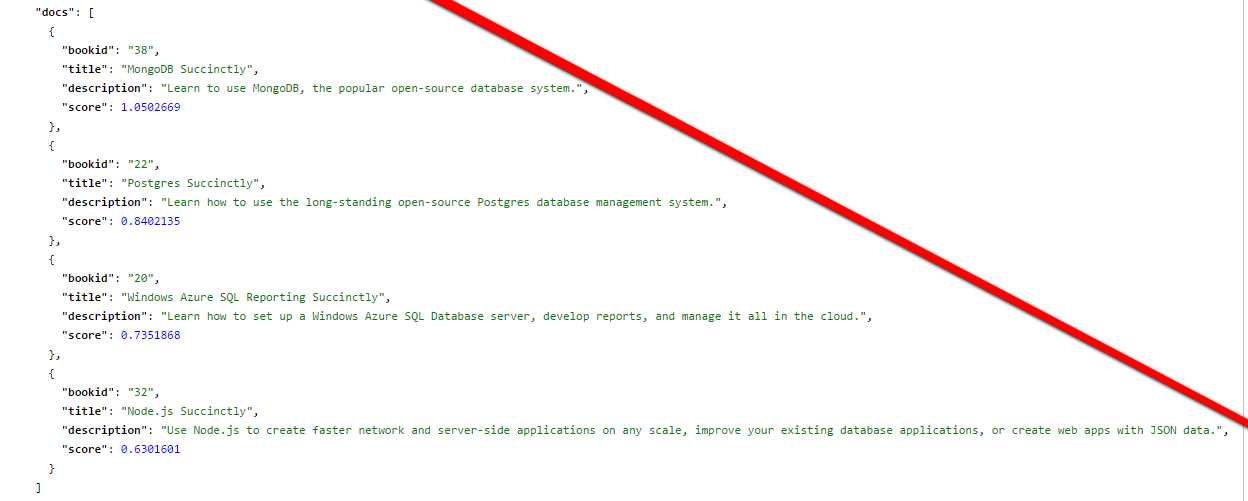

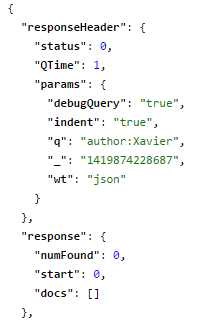

Let's try searching for my name only in authors. This should be something like "q=Xavier"; we'll use the following URL and see what happens:

Oddly enough, our query comes back with no results.

- No results for query Xavier

Initially this might seem like an odd response—after all, we know for sure that my name appears in the author field more than once, so how could our query not find anything?

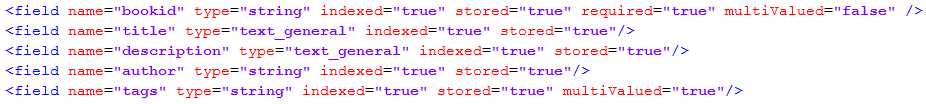

Re-open the Schema.xml file and refresh your memory on the definitions we previously created. You'll see author is a string, but the description type is text_general.

- Author is string and description is text_general

It’s the field type that makes the difference; string is a simple type, storing just a simple text string. To find it, you need to run a query for an exact match. This is great for faceting, but not so good for general searching.

However, text_general is a complex type, as it has analyzers, tokenizers, and filters. Additionally, within analyzers, it has both query and index time. Its main use is for general purpose text searching.

Once you understand the different field types, things get much easier.

Search for a Phrase in a Field

As we did previously with the author field, we can search for phrases. Let’s try to use our description:database query and refine it further by querying for description:"database system".

We can easily do this using the following query:

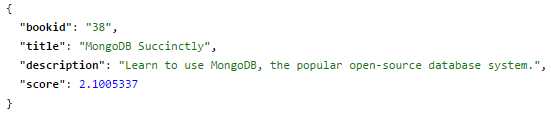

http://localhost:8983/solr/succinctlybooks/books?q=description%3A%22database+system%22&wt=json&indent=true&debugQuery=true |

We only got one exact match. Fantastic, our search works and gives us exact results, right? Not quite, as we don't really want to be absolutely specific when doing general searches.

- Exact match search

Proximity

What if we wanted to find not an exact match, but a match in close proximity? For example, MongoDB Succinctly had “database system”, but that left out Postgres Succinctly, which had “database management system”, which is a very close match that could be useful for our users.

To address this, we have something called proximity matching, otherwise known as the process of finding words that are within a specific distance of our match word.

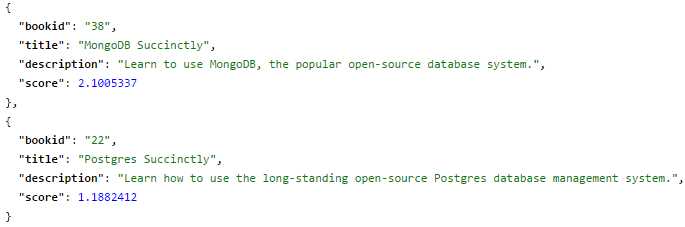

Change the query we just issued (the one that only returned one result) so that our q parameter now reads 'q = description:"database system"~4'. If you are entering this via a URL in your browser, the new query should look as follows:

http://localhost:8983/solr/succinctlybooks/books?q=description%3A%22database+system%22~4&wt=json&indent=true&debugQuery=true |

As you can see in the following figure, we now have two results, and more importantly, our score gives us an idea of the order of importance or relevance.

- Proximity search

Operators and Fields

It's possible to use operators for querying. For example, if I want to search for all books that have a description of databases AND use Azure as a technology, I would form my query term as 'description:database AND description:Azure'. Converting this to a URL, we end up with the following:

As you might expect, you can also do an OR search. For example, the following query term 'description:database OR description:Azure', turned into the following URL:

This yields four results. You can also match between fields, for example, searching for all books with tags 'aspnet' or with 'Net' in the title. The query term would be 'tags:aspnet OR title:net', and the following URL demonstrates this:

http://localhost:8983/solr/succinctlybooks/select?q=tags%3Aaspnet+OR+title%3Anet&wt=json&indent=true |

You can nest operators as much as you need to, but you must remember capitalization. It’s different to use AND vs and; this is an important point. If you get the capitalization wrong, your search won't work as expected.

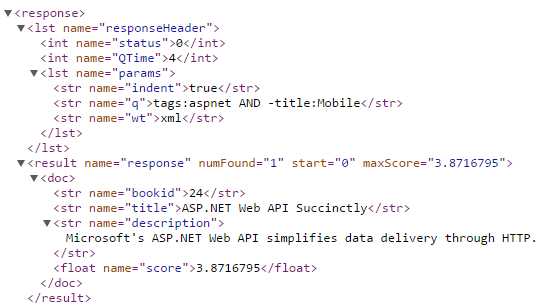

Not (Negative Queries)

It's also possible to perform a negative search, that is, a search where you specifically request NOT to include results for a given term. For example, you could search for tags:aspnet, and you will get two results: ASP.NET MVC 4 Mobile Websites and ASP.NET Web API. If we don't want any results that relate to mobile, we can use the following query term (notice the - symbol):

tags:aspnet AND -title:Mobile |

In URL format, it will look like this:

http://localhost:8983/solr/succinctlybooks/books?q=tags%3Aaspnet+AND+-title%3AMobile&wt=json&indent=true |

Try altering the URL to include only 'tags:aspnet' then include the 'AND -title:Mobile'. Note that the first form gives two results, and the second only gives one result, just as we might expect.

- Negative query result showing only one match

Wildcard Matching

As you've already seen in many places in this book (*:*), we've used wildcards quite a lot so far. There's more to wildcards than you might realize, however. Solr supports using wildcards at the end and in the middle of a word. A ? means a variation of a single character, while * means many characters.

In case you’re wondering, a '*' at the beginning of a phrase (called a leading wildcard or suffix query) was originally NOT supported in Solr. This has recently been changed, but please know that it's an incredibly inefficient search method, and not recommended for production use.

Let’s try some example wildcard searches. Create some searches (either in the Admin UI or with a browser URL) using the following query terms:

Try creating some URLs of your own to satisfy these queries, or simply just use the Admin UI. Once you understand how the position affects the operator, scroll down to see if your results match those in the following table.

Query | Result | Notes |

|---|---|---|

author:”Xavier*” |

| This query has zero results as you are doing a phrase search. |

author:Xavier* |

| Remove the quotes and we get the expected results. |

author:X*a |

| Works fine, as expected. Solr returns any author that starts with X and ends with a. |

author:*Morera |

| This gives us the results we expected, but remember placing the '*' in front of the term is inefficient. |

Due to the small sizes of our index and search data in these examples, we don’t see a great deal of difference in the query times. However, if we had a larger data set and index, you would easily be able to see which methods are the most efficient.

Range Searches

Range queries allow matching of documents with values within a specified range of values. In our example, we haven’t included any dates (or for that matter, any range-based data); if we had done so, in a field called createddate for example, we could have performed a query that looked something like:

createddate:[20120101 TO 20130101] |

This would have allowed us to search the field createddate for results that were contained in the lower and upper bounds enclosed by the square brackets. Here are a few more range examples.

- field:[* TO 100] retrieves all field values less than or equal to 100

- field:[100 TO *] retrieves all field values greater than or equal to 100

- field:[* TO *] matches all documents with the field

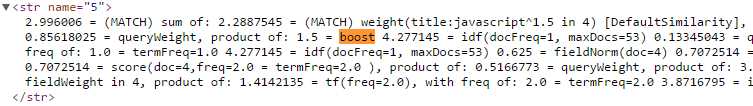

Boosts

Query time boosts allow us to define the importance of each field. For example, if you run a query for a specific term, and you are more interested in that term appearing in the title than in the description of the document, you might form a query term that looks like this:

In this case, you are applying a boost of "1.5" to whenever your term appears in the title, while still remaining interested if it is also present in the description.

I recommend that you use explain so that you can see how your boosting affects scoring. In our initial tour of the Admin UI in the query section, we mentioned that there is a checkbox called debug query that is used to display debug information. Enable it, and the response will come with a text that explains why a particular document is a match, or relevant, to your query. In this particular case, you can see boost being used to affect the score of your document.

- Boosting affects scoring

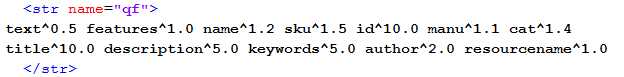

Boosting does not need to be performed on every query; likewise, every query is not performed only on the default field(df). You can specify the query fields (qf) in your Solrconfig.Xml, so that on every query, the desired boosts are applied automatically.

The following figure shows an example of a handler for the built-in sample collection (the collection we used before we defined our Succinctly books collection). As you can see, the handler has pre-specified which boosts should be applied when searching, and to which fields it should be applied automatically.

- Boost specified in handler

This is the essence of how you tweak your Solr application. You make small changes over time and analyze the results, log the searches your users are performing, then try the tweaks yourself against those searches. This process of trial and error can be tedious, but in the search industry in particular, it's often the best way to fine-tune things to provide the expected results.

It is important to take into consideration that df is only used when qf is not specified.

Keyword Search and CopyFields

Up until now, we’ve been doing mostly queries within fields, for example, author:Xavier Morera.

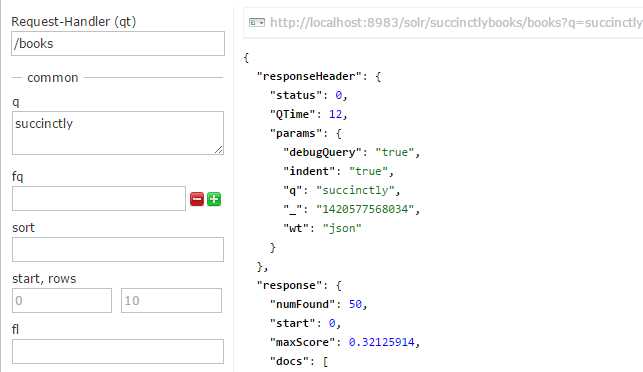

Imagine, however, that we wanted to search just for a keyword, such as “Succinctly.” This one should match all of the books in our collection, right? After all, every book in the series has this word in its title.

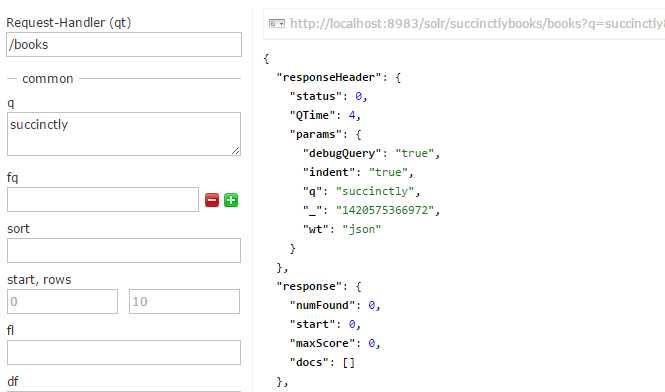

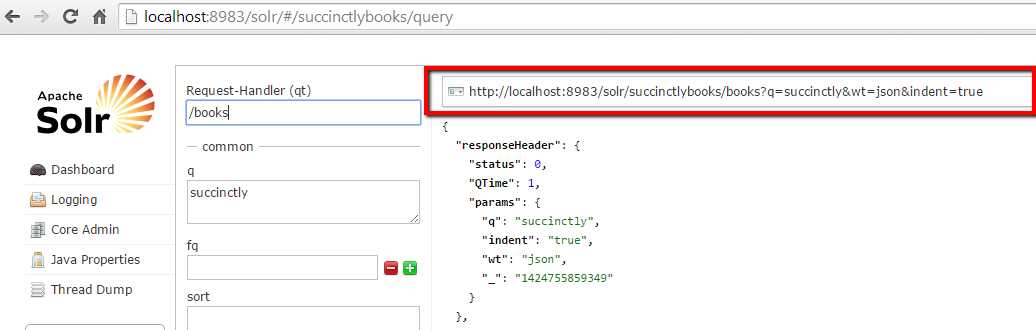

Not quite. Run a query from the Admin UI for the term 'Succinctly' and observe the results.

- No results for query “Succinctly”

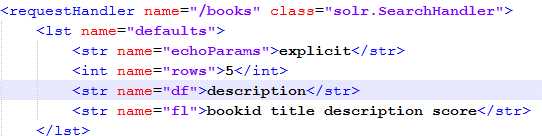

Why are no results returned? It’s very simple—let’s take a look at our Solrconfig.xml file right now to find an answer. Please find the /books request handler. As we can see in the following figure, we have a df of text. df stands for default field; therefore, we are telling Solr that our default search field is called text.

- Text is our default field

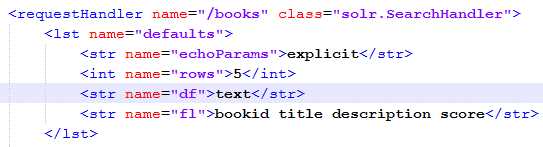

But if you look within Schema.xml for the copy field declaration for text, you will notice that it is commented out. Therefore, it is empty now, as no information is copied over to text during indexing.

- All copy fields commented out

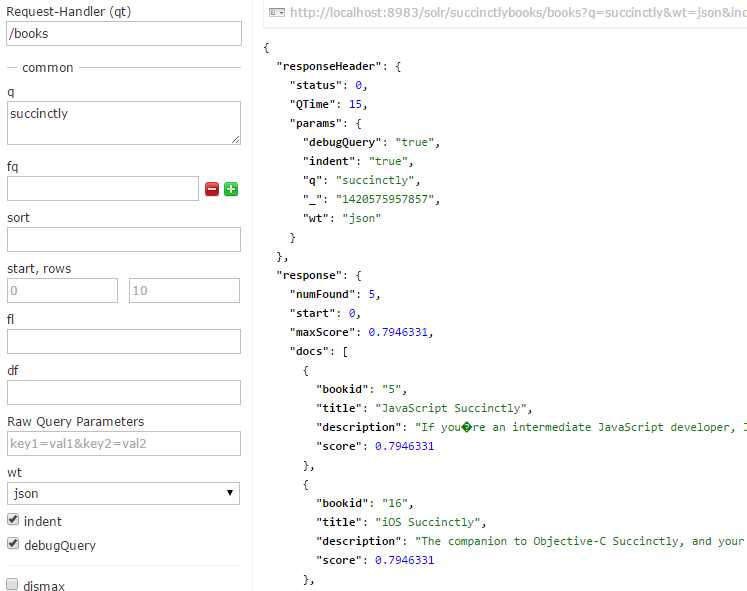

Let’s give it a try and modify the df so that it points to the description, which can be done in Solrconfig.xml. As you can see in the following figure, df has a value of description instead of text. Don’t forget to reload the core or restart Solr.

- Change default field to description

If we now re-run our previous query following the changes we made to our configuration, we should now see that we get much better results.

- Run query again

If you wish to use the direct URL, just enter the following into your browser:

http://localhost:8983/solr/succinctlybooks/books?q=succinctly&wt=json&indent=true&debugQuery=true |

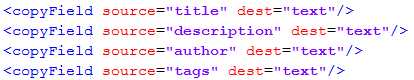

In this case, we are searching in a single field, so let’s revert back to text and create a copyField for each one we would like to have copied. This is done in the Schema.xml file.

- Copy fields

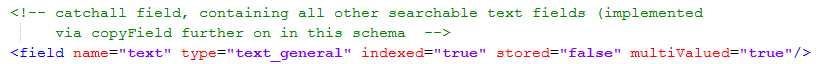

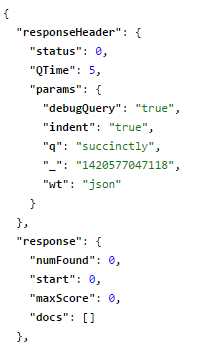

Reload and query again. You’ll notice it did not work—but why?

- Query did not work

This is the query:

http://localhost:8983/solr/succinctlybooks/books?q=succinctly&wt=json&indent=true&debugQuery=true |

The copyField is done when a document is indexed, so it is before the index analyzer. It is the same process as if you provided the same input text in two different fields. In a nutshell, you need reindexing.

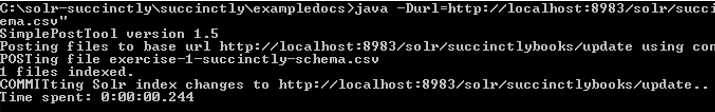

Reindex the way that you did using exercise-1-succinctly-schema-index.bat from exampledocs, from the command line.

- Reindex sample data

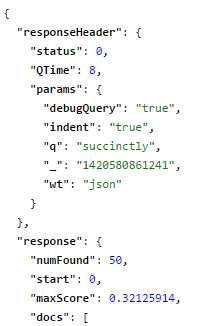

Run the query again. How many results should you get?

- Query again with 50 results

The answer is 50. Why? We have 53 documents, but the reindexing only considers our initial result set. We manually added the other three.

Synonyms

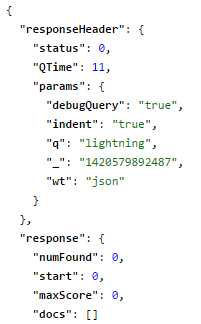

Synonyms are used in Solr to match words or phrases that have the same meaning. It allows you to match strings of tokens and replace them with other strings of tokens, in order to help increase recall. Synonym mappings can also be used to correct misspellings. Let’s try a simple test to illustrate what I mean.

Tip: To make sure that we have all of our sample data in our index, please open a command prompt, navigate to solr-succinctly\succinctly\exampledocs, and run the following batch file: exercise-1-succinctly-schema-index-fixseparator.bat. By doing so, you will reload the sample books into your index.

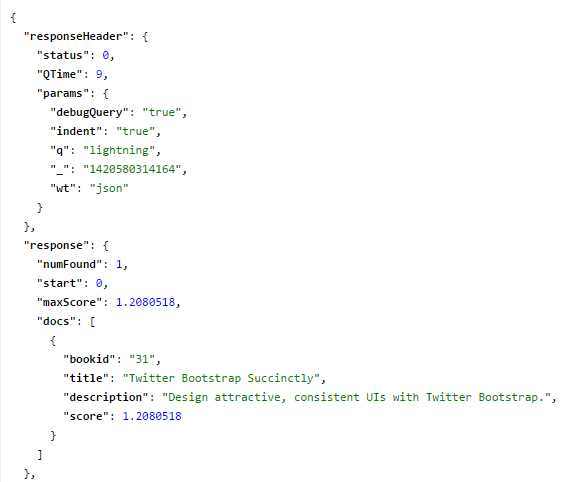

Run a query for q=lightning on our books collection; you should see no results found.

- Query for lightning has no results

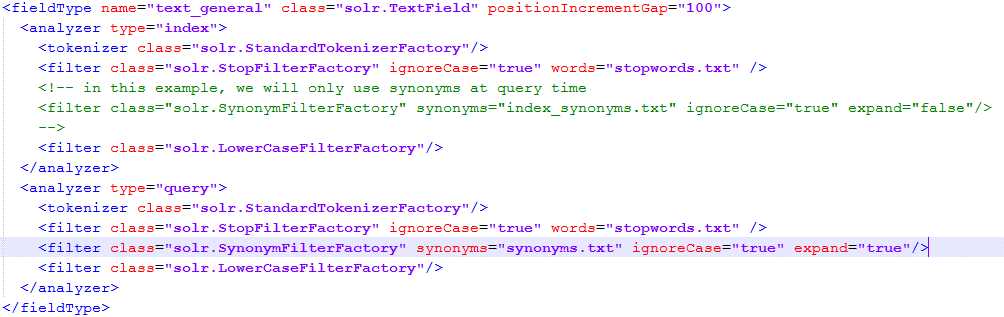

Now open Schema.Xml for the succinctlybooks collection, and go to our default field type, text_general. You can find it within the fieldtype name=text_general node, as you can see in the following figure. Within the analyzer node of type=query, you can see a filter of class=solr.SynonymFilterFactory. This indicates that your Solr has synonyms configured for any fields of type text_general that are calculated at query time.

Great! That means no re-indexing is needed, although it might potentially affect performance at a certain scale.

- Review text_general

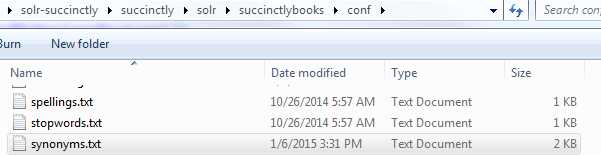

If you look closely at the filter for the synonyms, it has an attribute synonyms=“synonyms.txt”. This means that our synonyms dictionary is this text file, which is located in our conf directory for the succinctlybooks core.

- Figure 125: Location of synonyms.txt

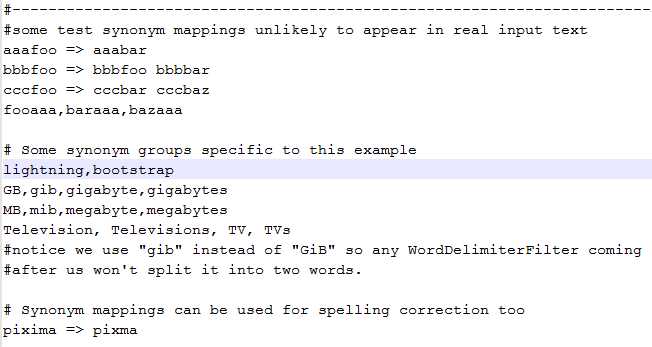

Open the file and add an entry (like for lightning) so that it is used as a synonym for bootstrap. We have comma-separated values.

You should have something similar to the following:

- Synonyms.txt file contents

Now try running the query for lightning again, using the /books request handler in the succinctlybooks core. You should get no results. As with most configuration changes, you'll need to reload the core for things to take effect.

- Reload and query for lightning

Now, my friend Peter Shaw’s Bootstrap book is there. (Which I personally recommend to every single developer who, like me, is UI challenged! It really makes a difference.)

Stopwords

Stopwords are how Solr deals with removing common words from a query. Common words are defined as standard English common words such as 'a', 'an', 'and', 'are', and 'as', along with many others. Any word that is likely to be commonly found in every sentence could be classed as a stopword.

In some cases, a word does not have any special meaning within a specific index. In our case, all documents have the word “succinctly,” so it provides no additional value when used. In a previous project that I worked on, I had to index all patents and applications worldwide; this lead to the word “patent” not having any special meaning.

Let’s try a query with q=succinctly. You should get the following results:

- Query for succinctly

Please remember that you can construct the URL for this query from the Admin UI, by running a query and clicking on the gray box at the top right.

- Where to click to construct query URL

All results are found, as the word occurs in every single document. The way to indicate which words should not be used in a query is via stopwords. This is done via the Solr.stopfilterfactory.

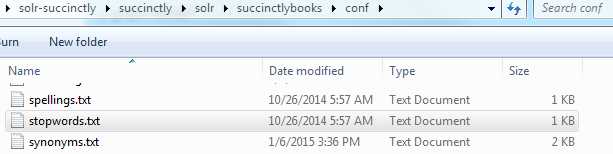

To add a stopword, you need to go to the conf directory, in the same location where we modified our synonyms.

- Location of stopwords.txt

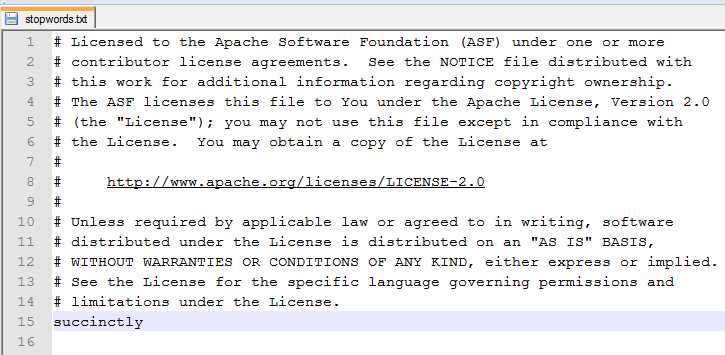

Open stopwords.txt and add the desired word.

- Contents of stopwords.txt

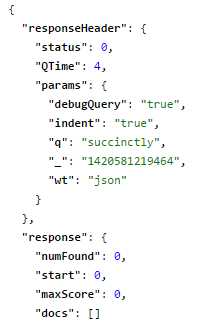

If you run the query now, all documents should still be returned, which means that the stopwords are not working. This is expected, because we just made a configuration change, but have not yet reloaded the core as required.

- No results yet

Reload the core and query again. No results were found, which is the outcome we expected.

Stopwords can be added both at query and at index time. It’s very useful at index time because if these words are removed from your index and they are very common, it helps with the index size. At query time, it is also useful, as no reindexing is required.

Summary

In this section, we have learned some of the basics of searching using Solr. This is an extremely large subject that could spawn hundreds or even thousands of pages, but this kick-start puts you in a nice position to move forward on your own.

In the next section, we will discuss user interfaces with Solr.

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.