CHAPTER 2

Architecture of an Enterprise Search Application

Where and How

From an architectural point of view, there are two different areas that need to be discussed. The first one is where the search engine fits within your solution, the second one is the how to of Solr’s architecture.

Placing the Search Engine

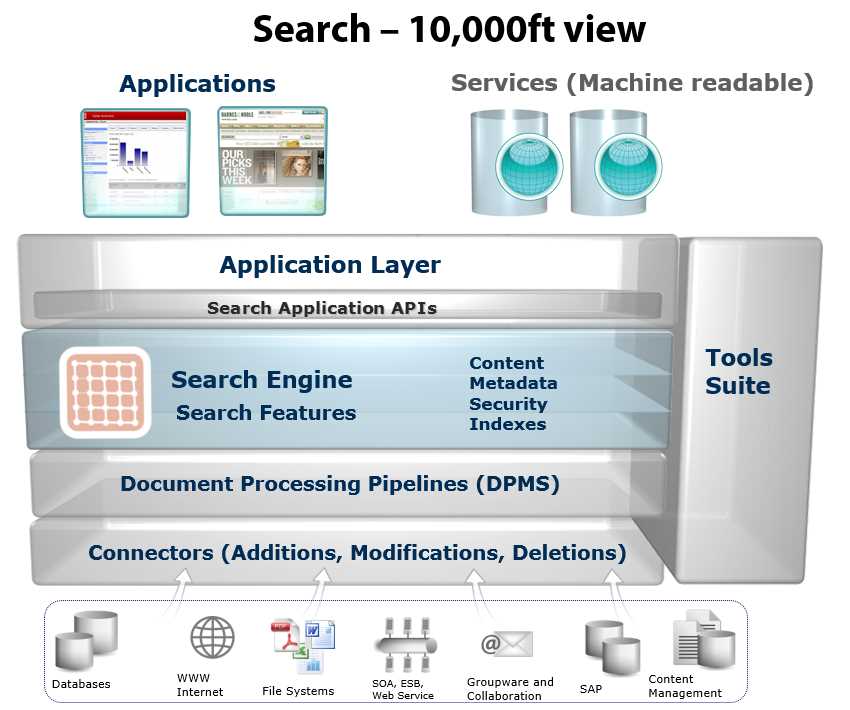

Let’s take a look at the following figure, something I like to call the search application 10,000-foot view.

- Application architecture

It is absolutely clear that application architectures can be wildly different, but let’s make a few assumptions here and generalize to some degree on some of the most general use cases, starting from the top of the diagram.

We can assume that our application will have a UI, which can be built in ASP.NET Web Forms, MVC, AngularJS, PHP, or many other UI frameworks. Our application also has an API that might be used for other applications to connect to, such as an iOS or Android mobile application.

Eventually we get to the application, which may be your key source of income, and you are very proud of it. If you’re like I was before I discovered Solr, you probably have something really nice, but that has technical elements that just do not feel right. You may even have provided a not-so-nice user experience that frustrated a few—or even a few thousand—users.

This is where search comes in. You connect to the search engine via the search API. Solr provides an innovative RESTful interface for your needs, or you can choose a client like SolrNet or SolrJ. This all means that your application can run a query or two, refine and provide the user with Indexes to the exact resulting Content, and through the use of MetaData retrieve the required results with the appropriate levels of Security.

Let’s go to the bottom of the diagram for a moment to understand the multiple data sources that can provide data to your search engine. Most applications get their data from a database, like SQL Server or MySQL. However, in many cases they could also be getting it from a NoSQL database, content source, other applications like a Content Management System, or the file system.

There are multiple ways to retrieve the data that we will be adding to the search engines. One of them is what’s called a connector, which retrieves data from the store and provides it to a document-processing pipeline.

The document-processing pipeline, also known as DPMS, takes the content from a data source, performs any necessary transformations, and prepares to feed the data to the search engine.

Inside the Search Engine

Solr is hosted in an application container, which can be either Jetty or Tomcat. For those of you with little to no experience with Jetty or Tomcat, they are web servers just like Internet Information Services (IIS) or nginx.

For development purposes, Solr comes with Jetty out of the box in an extremely easy-to-use, one-line startup command. However, if you wanted to host within Tomcat, you need Solr.war. For those of you that don't know Java, .war stands for Web Application aRchive.

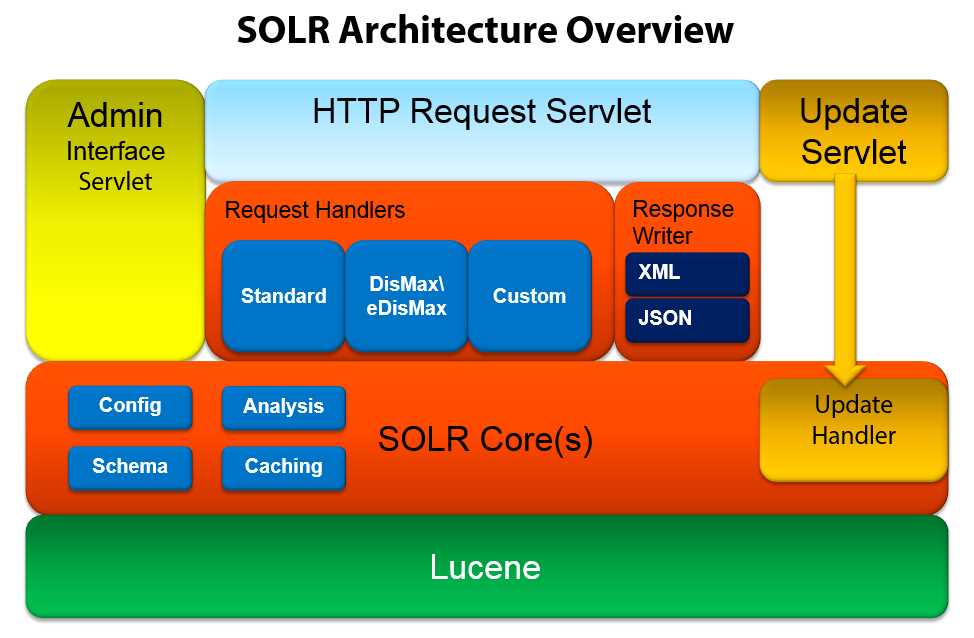

Let’s now take a look at the architecture, starting from the bottom.

- Solr architecture

The first and most important point is that Lucene, a free, open-source information retrieval software library, is the actual search engine that powers Solr. This is such an important point; Solr has actually been made part of the much larger Apache Lucene project.

It really caught my attention when I first discovered Solr within Lucene, so much so that I simply had to investigate it further, and I'm very glad I chose to do so. Lucene is written in Java, was originally created in 1999 by Doug Cutting, and has since been ported to multiple other languages. Solr, however, continues to use the Java version.

There are many other projects that extend and build on Lucene’s capabilities. One of these is ElasticSearch, which even makes for a good Solr contender (though arguments are accepted).

On top of Lucene, we have the Solr core, which is running an instance of a Lucene index and logs along with all the Solr configuration files. Queries are formatted and expanded in the way in which Lucene is expecting them, meaning you do not need to do this manually (which can be tedious and complex). These queries are configured and managed (along with how to expand them, and configure the schema details) in the files schema.xml and solrconfig.xml. In simpler deployments, you can often get away with modifying only these two files. What follows is the very short explanation of the purpose of each one:

- Schema.xml contains all of the details about which fields your documents can contain and how those fields should be accessed with when adding documents to the index or querying those fields.

- Solrconfig.xml is the file that contains most of the parameters for configuring Solr itself.

If you look within Solr Core(s) in the Solr Architecture diagram in Figure 4, you can see where analysis and caching reside. Analysis is in charge of processing fields during either query or indexing time. Caching allows performance improvement.

Initially Solr only supported a single core, but more recent versions can support multiple cores, each one of which will have all the components shown in orange on the architecture diagram. Solr also uses the word “collection” very often; in Solr-speak, a collection is a single index that can be distributed among multiple servers. When you download and start Solr, it comes with a sample index called collection1, which you can also call a core.

To be very clear, let’s define some common Solr nomenclature:

- Core: A physical search index.

- Collection: A logical search index that can be made up of multiple cores.

Things get a bit more complex when you introduce SolrCloud Replication and start talking about Shards, Leaders, Replicas, Nodes, Clusters, and ZooKeeper; these, however, are advanced concepts that would belong in a second book about the subject.

Request handlers are responsible for defining the logic executed for any request received by Solr. This includes queries and index updates.

Once a query is received, it is processed by the query parser. There are many parsers available, such as the Standard query parser, DisMax, and eDisMax, which are the most commonly used. You can, however, create your own custom parser if you wish.

In Solr 1.3 and earlier, creating a custom parser was the only way forward. Since version 1.3, DisMax became the default query parser while still maintaining the ability to customize things when needed.

Response writers are in charge of preparing the data in multiple formats to be sent back to the client, for example, in JSON or XML-based data.

The HTTP request servlet is where you connect to Solr, and the update servlet is used to modify your data via the update handler.

Note: If the term "servlet" is a strange one, don't worry. Think of a servlet as an endpoint on a web server. Servlets are specific to the Java world, and are similar to controllers in other web technologies.

Eventually we reach the admin interface servlet, which provides Solr’s default administration UI, something you'll come to rely on once you have deployed your search engine.

We could easily keep peeling away layer after layer and getting into more and more complex and advanced functionality. However, that's not the purpose of this book, so we'll keep the details at a reasonably simple level.

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.