CHAPTER 9

Ansible Playbook

An Ansible playbook is a file written in the Ansible automation language, and it’s based on the YAML format. The playbook is Ansible’s means to perform configuration, deployment, and orchestration.

As opposed to the ad-hoc commands we discussed previously, playbooks can declare configurations, but they can also orchestrate the steps to be executed. A playbook contains tasks that can be launched synchronously or asynchronously, depending on the use case.

One can think of a playbook as an entry point for all of the operations that we would like to execute in a given order against one or a set of managed hosts. In that sense, playbooks are meant to be kept in the source control (such as Git) and should be treated as any other application code.

Basic structure

The first thing to know about an Ansible playbook is that it’s written in YAML. There are just a few rules to pay attention to when writing the code:

- The file typically should have the standard yml extension.

- The file must start with (three dashes) ---.

- The file is indented by two spaces (not tabs), as emphasized by the orange highlights in the following code snippet.

- The items of the same level must be aligned.

Code Listing 49: Simple playbook example (webserver.yml)

--- - name: Web Server Playbook hosts: webservers become: yes tasks: - name: Pinging web server ansible.builtin.ping: data: pong |

We have specified the name of the play, the hosts to which this code is going to be applied (group in the inventory file), and the become:yes option (to enable privilege escalation). These settings are global to the playbook.

We can see that there is a tasks section defined and aligned by two spaces. The tasks section is a list of individual tasks identified by the name, the module, and other possible arguments. It’s very similar to what we have seen previously with the ad-hoc commands.

Although we see only one task in the previous example, we can specify more of them, and as we are going to see in the following chapters, combine them with variables, handlers, or roles to obtain a very powerful orchestration.

Figure 30: Typical playbook structure

Executing the playbook

To execute the playbook, we use the ansible-playbook command.

Code Listing 50: Execution of the webserver.yml playbook

$ ansible-playbook webserver.yml |

The result is going to look similar to the following.

Code Listing 51: Playbook output

(avenv) [vagrant@amgr simple_playbook]$ ansible-playbook webserver.yml PLAY [Web Server Playbook] ************************************************************************** TASK [Gathering Facts] ****************************************************************************** ok: [193.168.3.161] ok: [193.168.3.160] TASK [Pinging web server] *************************************************************************** ok: [193.168.3.161] ok: [193.168.3.160] PLAY RECAP ****************************************************************************************** 193.168.3.161 : ok=2 changed=0 unreachable=0 failed=0 skipped=0 rescued=0 ignored=0 193.168.3.160 : ok=2 changed=0 unreachable=0 failed=0 skipped=0 rescued=0 ignored=0 |

We can clearly see that the output contains the output grouped under the names of the sections as defined in the webserver.yml:

- Gathering Facts: This is the phase of retrieving information about all of the hosts listed in the inventory file, and that are in the context of the playbook. We can disable it by specifying the option gather_facts: false in the default section of the playbook.

- TASK [task_name]: For every task defined in the playbook and executed, there will be one section in the result. In our case, we have only one task. Pinging web server is executing the module ping, and it is displaying that the operation has been completed successfully, specifying the name of the host, as well.

- PLAY RECAP: After each run, there is a summary of the playbook execution stating if there were failures during the execution, and it constitutes a very nice report of the playbook execution itself. We can clearly see that there are a few pieces of information available:

- ok=2: There are two operations completed successfully.

- changed=0: Something has changed on that particular host. In our case, ping doesn’t change anything, really.

- unreachable=0: If playbooks are not able to reach some hosts, this will be shown here.

- failed=0: If any operation fails, this will be shown in the recap, as in the task itself with more details.

- skipped=0: Shows if there are tasks that are not being executed due to some conditions set.

- rescued=0: Tasks that failed but recovered execution. There is a fallback solution in case a task fails to execute.

- ignored=0: If there are some errors being ignored, the count will be shown here.

Limit option

There are a few options when using ansible-playbook commands, such as limiting the hosts against which we would like to run the command. This is done by using the --limit argument. This is useful if we would like to target just one server, for instance, without changing the playbook itself.

Code Listing 52: Targeting specific hosts

$ ansible-playbook --limit 192.168.3.160 webserver.yml |

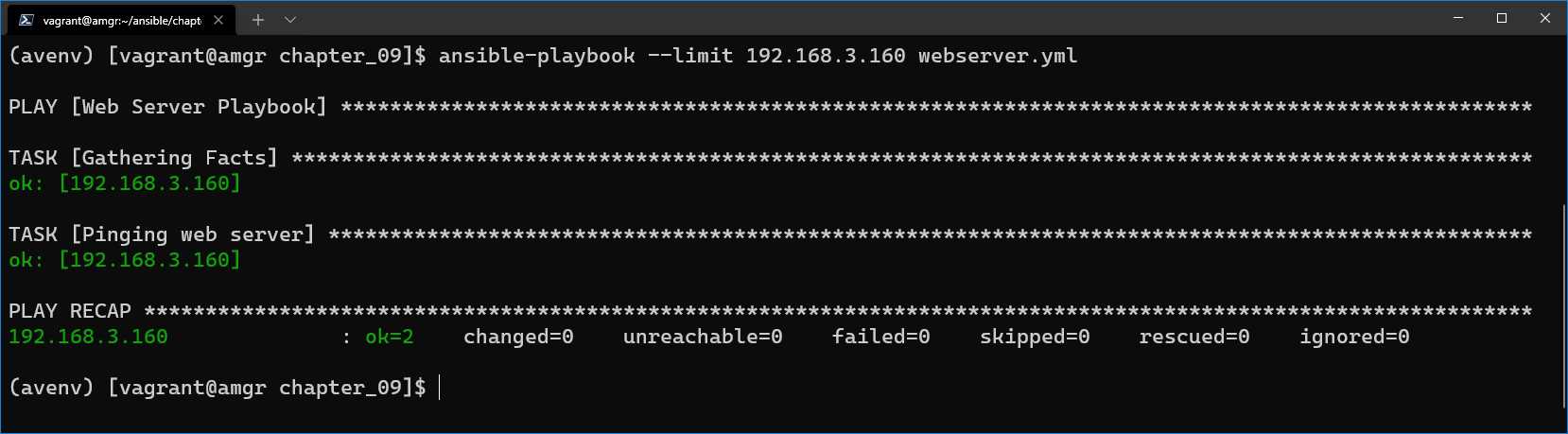

The result will show that the command was executed only on one server, as specified in the command.

Figure 31: Command executed only on one server

Checking the syntax

If we would like to check the syntax of the playbook without executing it, there is the --syntax-check option. This is very handy for figuring out if there are issues with the file.

Code Listing 53: playbook syntax checking

$ ansible-playbook --syntax-check webserver.yml |

If an error is found, the line containing the issue will be displayed.

Dry run

To run the “dry run,” which is like a test mode, there is the -C option. Dry run mode will show the output of the specified change, but without changing the managed hosts. This is extremely useful when testing, as we can see which changes would occur if we execute this command.

Code Listing 54: Dry run option when executing playbooks

$ ansible-playbook -C webserver.yml |

Variables

We have seen the most basic playbook content and how to execute it. Now we have to look into how to parametrize and make the playbooks more useful by specifying variables.

Variables provide a very convenient way to handle dynamic values. Variables could be about anything, such as a list of users, a list of software packages to install or uninstall, and services to start or stop.

It’s obvious that having everything statically defined in the playbook would work, but it would also be a bit more cumbersome to handle, as this would typically result in a larger code base with some repetition, which would potentially increase the possibility of errors in code.

Naming convention

The variables have to start with a letter, and they can include underscores and numbers.

Table 9: Variables: naming convention

Valid variable name | Invalid |

|---|---|

account_name | account name account-name account.name |

account_nr_1 | account-nr1 accountnr#1 account$1 1_account |

Variables scope

The scope of the variable is the context within which it is defined. In other words, this defines in which parts of the program variables will be seen, applied, or used.

Ansible defines three scopes, summarized in the following table.

Table 10: Variables: scope

Scope | Description |

Global | This is set by configuration, environment variables, and the command line. It is set to all hosts. |

Host | Directly associated to a specific host or host groups (as defined in the inventory file). Those are variables defined in the inventory or in the host_vars directory. |

Play | Scope applies to the play in which variables are declared. It applies to all hosts in the context of the current play. The vars directive in the playbook is where the variables are declared. Additionally, they can be defined by the include_vars task. |

If a variable is defined in several scope levels, the value of the level that has the precedence would be taken as the variable value. The narrower in scope we go, the more precedence it has.

Play scope overrides the host variables, which override the global variables, which have more precedence over the variables defined in the inventory file. However, if the variable value is defined in the command line directly while executing the command, it has the highest precedence. By providing the -e option in the ansible-playbook command, we can override any value.

Declaring variables in the playbook

In the playbook, we can define the variables in two possible ways: either by declaring them explicitly using the vars directive, or by using the vars_files directive to include the file(s) where the variables are declared (in our case, in the vars/users.yml and vars/services.yml files).

Code Listing 55: Variables—declaring

--- - name: Example with vars hosts: all vars: user_name: john user_description: "standard user" - name: Example with vars_files hosts: all vars_files: - vars/users.yml - vars/services.yml |

We can then reference those variables in the playbook by placing the variable name between double curly braces: {{ name_of_variable }}.

Code Listing 56: Variables—using

--- - name: Example with vars hosts: all vars: user_name: john user_description: "standard user"

tasks: - name: Show user name debug: msg: "{{ user_name }} - {{ user_description }}" |

In this snippet, you can see that we are using the debug module. This module is useful when we want to display some information to the console, in this case the variables defined. The two variables previously defined are stored in the msg argument of the module. An important thing to notice is that we placed the variables between quotes.

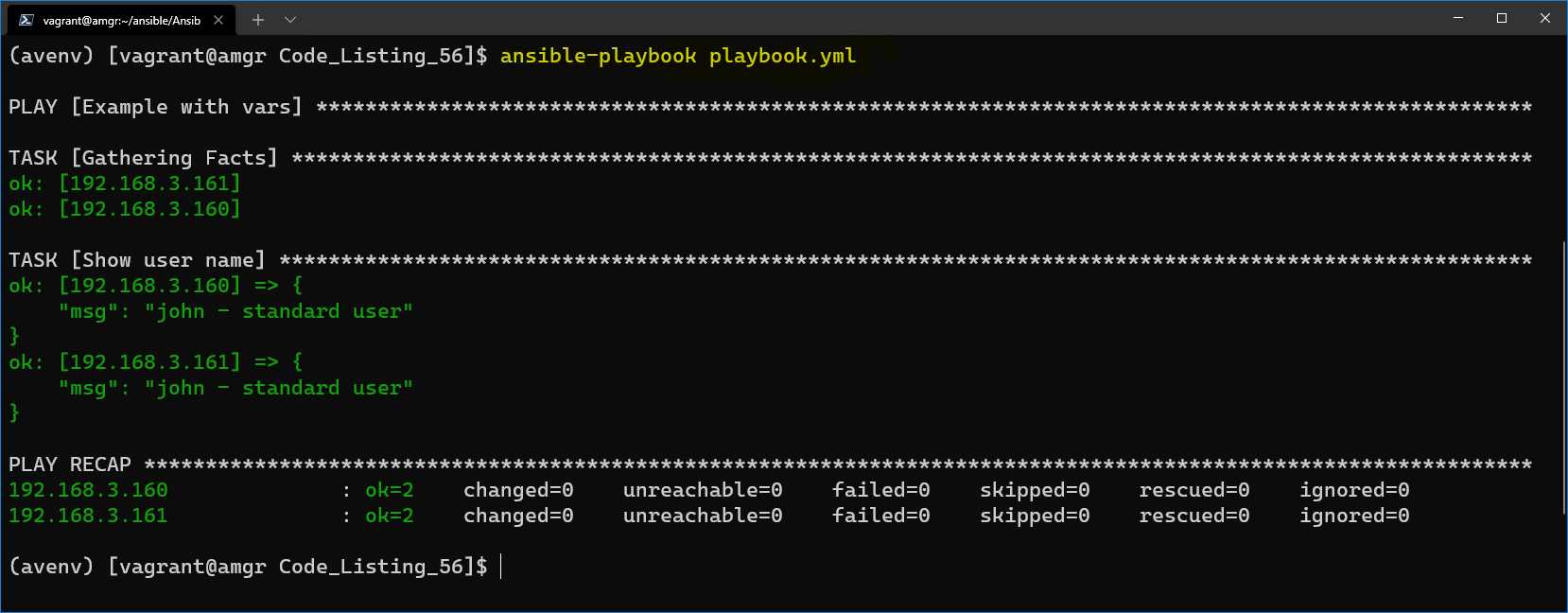

Let’s execute this code and see what the output will be, as shown in the following figure. We can clearly see the “msg”: “john – standard user” is displayed in the output.

Figure 32: Retrieving variable values

This is the same output we would have when using the the var_files directive. In the users.yml file, we would place the same content as in the vars section.

Code Listing 57: Content of the users.yml file

user_name: john user_description: "standard user" |

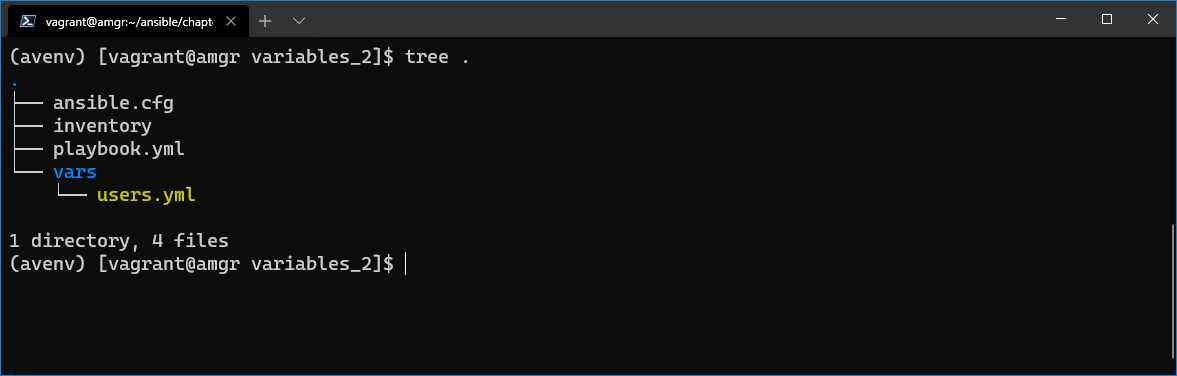

By looking at the folder structure, we can see there is a users.yml file in the vars folder.

Figure 33: Folder structure with vars directory

It’s worth noting that we can also define a list or dictionary of parameters.

Code Listing 58: Playbook with a list

--- - name: Example with list hosts: all vars: users: - john - mark - bob

tasks: - name: Show user name debug: msg: "{{ users }}" |

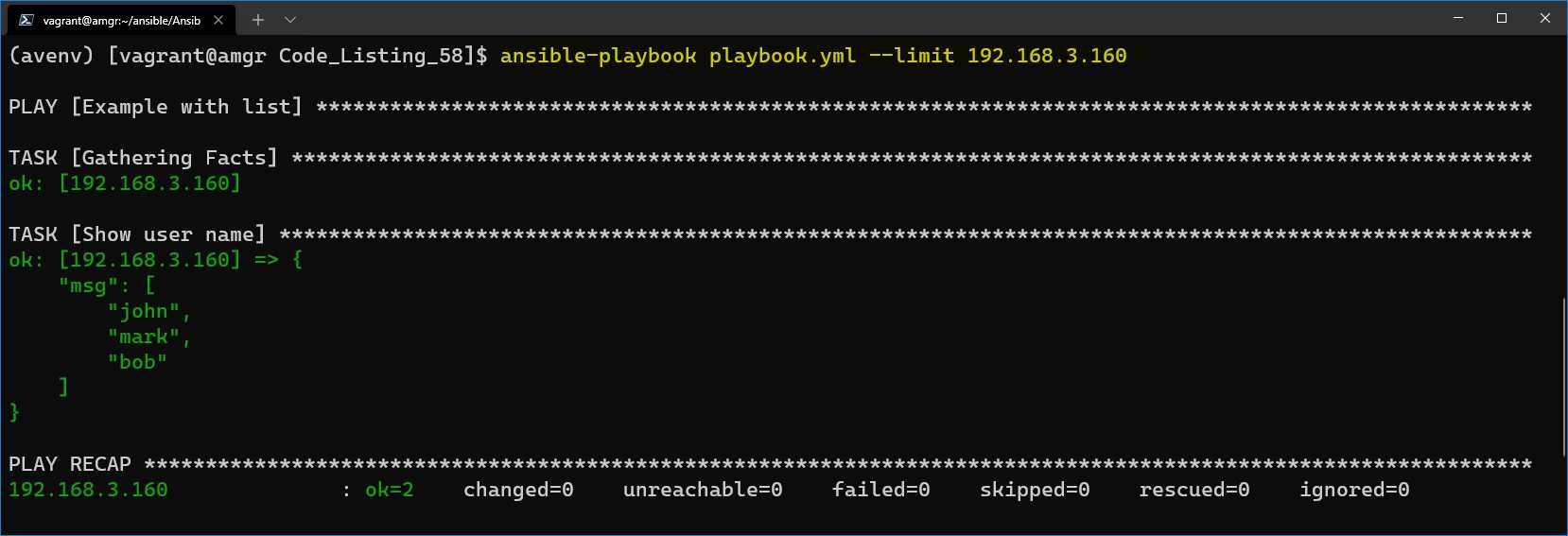

This code returns the following result.

Figure 34: Result by using a list

Or we can define a dictionary of values, like in the following.

Code Listing 59: Playbook with dictionary

--- - name: Example with list hosts: all vars: users: john: name: john default_password: john1234 mark: name: mark default_password: mark1234 bob: name: bob default_password: bob1234 tasks: - name: Show user name debug: msg: "{{ users['john']['name'] }} - {{ users['john']['default_password']}}" |

This code returns the following result.

Figure 35: Running playbook by using dictionary variable

Declaring group or host variables

Group or host variables can be declared either in the inventory file or as specific files in the group_vars or host_vars directories, in the same location as the inventory file.

The naming convention for files is driven by using the same host names or group names as defined in the inventory file.

Say we had an inventory file as follows.

Code Listing 60: Inventory file

[webservers] web160 web161 [load_balancers] lb [databases] db |

The following is the folder structure with files containing group or host files with the same names as defined in the inventory file.

Code Listing 61: Directory structure of group and host vars

\ | |-- web160 | |-- web180 |-- playbook.yml |-- ansible.cfg |-- inventory |

These variables will be loaded by default, depending on what is declared in the playbook hosts section.

Looping through variables

Ansible defines the loop keyword that enables looping through variables within a given task. A special variable called item holds the current item value during the iteration through values.

Code Listing 62: Looping

--- - name: Looping through a list of variables hosts: all vars: packages: - httpd - python - mysql tasks: - name: List packages debug: msg: "{{ item }}}" loop: "{{ packages }}" |

When we execute the playbook, in the output we can see three distinct msgs being returned to us. In fact, this is executing the task as many times as there are items in the list.

Figure 36: Result of looping through variables

Conditional statements

Ansible supports conditional statements. Similar to an if statement in programming languages such as Python or C#, Ansible uses the keyword when to check whether a condition is being satisfied or not.

Code Listing 63: Conditional statement example

--- - name: Conditional check for true hosts: all vars: preinstall_package: false tasks: - name: List packages debug: msg: "executed" when: preinstall_package |

In this case, the debug task will not be executed, as the preinstall_package is set to false. We can clearly see in the output that the task is skipped.

Figure 37: Conditional statement result

Checking for true or false values is just one of the possibilities. There are other predefined keywords, such as is defined, where the variable is checked for its existence. The following table defines other possibilities.

Table 11: Conditional statements

Operation | Example |

|---|---|

Equal “some string” Equal some number | package_name == "httpd" port_number == 80 |

Less than Less than or equal to Greater than Greater than or equal to | port_number < 80 port_number <= 80 port_number > 80 port_number >= 80 |

Not equal to | package_name != "httpd" port_number != 80 |

Variable exists Variable doesn’t exist | port_number is defined port_number is not defined |

Boolean check for true Boolean check for false 1, True, yes: evaluate to true 0, False, no: evaluate to false | user_exists not user_exists |

Value present in a list of values | username in user_list |

Conditions can be multiple, and we can separate them by using the or and and keywords.

Code Listing 64: Using and in condition

when: username == “john” and groupname == “admin” |

The equivalent to the and statement can also be written as a list.

Code Listing 65: Alternative syntax for conditional and

when: - username = "john" - groupname = "admin" |

Combining loops and conditional statements

With the knowledge of how to write loops and conditional statements, we can certainly combine the two, making the playbook execution even more powerful.

Code Listing 66: Combining loop and when statement

--- - name: Conditional check for true hosts: all vars: users: - john - mark tasks: - name: List packages debug: msg: "executed" loop: "{{ users }}" when: item == "john" |

As you may already expect, this task will be executed only if the name of the user is john.

Figure 38: Result—loop and when combined

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.