CHAPTER 1

Introduction

Millions of people are accessing all kinds of Internet services. We are living in an era where there is a need for highly responsive and robust applications to serve exact user needs. The typical user is affected by a large amount of information, and because of a proliferation of services of all kinds all across the Internet, the user’s attention span is very short, and a few seconds of unresponsive systems might mean that an item won’t be sold, or a blog article won’t be read.

At the same time, the current technology allows us to have interconnected systems, grids of servers, data centers, cloud infrastructure, and multi-core machines. The computing power of a CPU, GPU, RAM, and HDD space costs have dropped substantially. This practically enables the processing of the Internet of Things (IoT), online streams of data, big data, machine learning, and artificial intelligence, among others.

When building applications, we can now effectively concentrate on making systems in a different way compared to the past. Today we can effectively utilize resources to work together and constitute a single application platform. This obviously brings a lot of new opportunities, and with them some challenges—as usually nothing comes for “free.”

We are living in a new world full of opportunities given by the technological advance. Let’s take a look at a very high level of technology evolution to understand better what is going on:

Table 1: Technology evolution

Past | Present |

One server | Multiple servers, cloud systems |

Few users | Sometimes millions of (concurrent) users |

One CPU core | Multiple CPU cores |

Very limited RAM | Potentially nearly unlimited and cheap RAM |

Very limited HDD space | Potentially unlimited and cheap HDD space |

Slow and expensive network | Fast and cheap expandable network |

Few megabytes of data | Large data sets, big data management |

Everything got bigger, distributed, and parallelized!

While there are several approaches to implementing a multithreaded, concurrent, scalable, and distributed system, the actor model paradigm is recently (re)emerging. As we are going to see, this is not a new approach, but certainly a good one that is worth exploring. This book is fully dedicated to Akka.NET, an actor model framework written exclusively for Microsoft.NET.

Short history of actor model and Akka implementation

Let’s start from the very beginning. If you are very new to the actor model, you might be surprised that it is not a new concept—it originated in 1973 with the computer scientists Carl Hewitt, Peter Bishop, and Richard Steiger. The concept has been captured in a publication called “A Universal Modular Actor Formalism for Artificial Intelligence IJCAI'73.”

This paper proposes a modular actor architecture and definitional method for artificial intelligence that is conceptually based on a single kind of object: actors (or, if you will, virtual processors, activation frames, or streams). The actor model on its own is based upon a mathematical model of a concurrent computation.

Fast forward to the current days: The Akka.NET framework is an implementation of an actor model. It was introduced in 2014 by Aaron Stannard and Roger Alsing. Akka.NET itself is a port of the Java/Scala Akka framework, which was introduced earlier on in 2009.

Figure 1: Actor model short history

Akka.NET is a community-driven port, and is not affiliated with the Lightbend company, which made the original Java/Scala version. The first version of Akka.NET was released in 2015. The latest version (1.3) is .NET Core-compatible.

Actor model deconstructed

Programming with the actor model is not only about Akka.NET, which is just one implementation of it.

There are other programming languages, such as Erlang, Elixir, Pony, and Scala, that have been written around the idea of the actor model and, in addition to these, quite a few frameworks are available.

Microsoft alone has recently made quite a contribution, with two implementations of frameworks, Microsoft Orleans and Service Fabric, and it supports actors on Microsoft Azure. On the other hand, an alternative implementation of the actor model from one of the creators of Akka.NET is Proto.Actor, which supports multiple platforms (.NET, Go, JavaScript, and Kotlin).

We can say that the actor model is more like a programming paradigm than a set of tools.

To implement the actor model, there are some fundamental rules to follow:

- Actor contains all the computations.

- Actors can communicate only through messages.

- Actors can change their state or behavior.

- Actors can send messages to other actors.

- Actors can create a finite number of child actors.

Akka.NET fully adheres to these rules.

Why use Akka.NET?

Akka.NET simplifies the building of scalable, concurrent, high-throughput, and low-latency systems. Let’s look at some of the ways Akka.NET makes the life of software developers a bit easier.

No manual thread management

Anyone who’s been involved in writing a multithreading system knows how difficult it can be to write, debug, and test an application. With Akka.NET, we can now safely rely upon the framework to handle the multithreading capabilities and make sure the code is thread safe.

High(er) level of abstraction

Akka.NET offers a higher level of abstraction, which makes everything in the system be considered an actor. The framework itself is built upon enabling communication between the actors through message passing.

On the surface, actors look a lot like the objects in object-oriented programming (OOP). If we think about it, OOP is first and foremost about message passing and abstraction. The actor model is all about independent actors maintaining state and passing messages to each other. This sounds very similar, right?

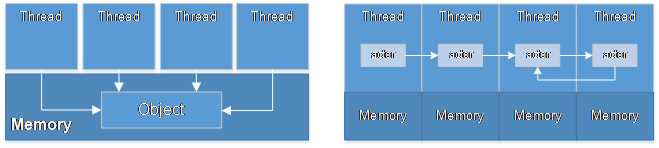

The traditional OOP languages (C#, Java, etc.) weren't designed with concurrency as a first-class use case. While they do support the ability to spawn multiple threads, anyone who's done multithreaded programming with these languages knows how easy it is to introduce race conditions (for example, data desynchronization or corruption). From that perspective, it would be really useful to compare the two paradigms when it comes to thread management and memory access:

Actors are following the share-nothing philosophy, while typically the OOP languages are not truly built around parallelism.

In the actor model, there are no race conditions, which results in simpler code. The share-nothing philosophy of actors also means that the actors don’t have to live on the same machine—we can spawn actors on different nodes and make them collaborate “natively.”

Figure 2: Comparison between the OOP vs actor-model approaches to multithreading

Scaling up

Because the Akka.NET framework is managing concurrency for us, we are able to scale up the servers on which the application is running. By adding additional CPUs, the system can have an effective usage of those shared resources without us writing any additional code.

Scaling out

The Akka.NET framework is effectively helping to scale out as well, due to its share-nothing philosophy, as mentioned earlier. By adding additional nodes, once again without us writing any particular implementation, and just through some configuration, the application can effectively use those resources. This is a big win, as we can concentrate on delivering value to our customers rather than writing infrastructure code that enables distributed collaboration.

Fault tolerance and fault handling

Akka.NET offers a way to deal with failures. Unlike the classic synchronous model where each consumer of a component needs to deal with component failures, Akka.NET and the asynchronous model direct failures to dedicated fault handlers. This brings a very controlled way of propagating errors.

Common framework

All of the above-mentioned features make Akka.NET a framework that has a lot of capabilities. Having it all available in one place makes it easier for teams to handle the various complex aspects in a single framework, and makes the learning easier than having to master several technologies to achieve the same result.

Where to use Akka.NET?

Akka.NET and its actor-model framework are practical for use in all kind of scenarios:

- Transactional application: Financial, statistical, social media, telecoms, etc.

- Batch processing: Actors would allow dividing the workload between them.

- Services: REST, SOAP, and general communication services like chats or real-time notifications.

When it comes to the Microsoft.NET framework, we can practically use the framework in every imaginable way:

- As an application back-end in a service application (WCF, ASP.NET Web API, etc.).

- As an application front-end in WPF or Windows Forms, used for routing messages to the underlying Akka.NET back-end (or similar).

- In web applications on ASP.NET MVC and Web Forms, used in a similar way as mentioned previously.

- In Windows Services to handle all sorts of messaging.

- In console applications.

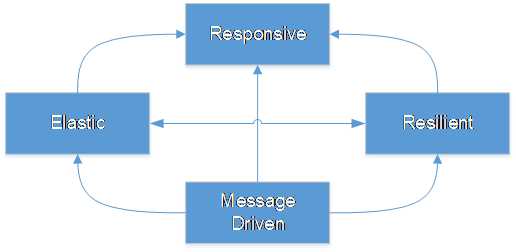

The Reactive Manifesto

Akka.NET adheres to the principles defined by the Reactive Manifesto. The Reactive Manifesto proposes a coherent approach to systems architecture in order to build systems that are more robust, more resilient, more flexible, and better positioned to meet modern demands.

Figure 3: Reactive Manifesto

As you can see in Figure 3, the Reactive Manifesto urges systems to have the following characteristics.

Responsive

The system responds in a timely manner, and it focuses on providing rapid and consistent response times so that the quality of service is constant. As a benefit of such a system, the error-handling is simplified, meets the user expectations, and encourages further interaction.

Resilient

In general, “resilience is the ability to provide required capability in the face of adversity,” as defined by the International Council on Systems Engineering, and in software-engineering terms, this would mean that the system stays responsive in the face of failure. There are several solutions that would help the system to stay resilient—such as replication, containment, isolation, and delegation. These are all in the context of how to handle the failures by not affecting the system as a whole, and how to recover from them successfully.

Elastic

An elastic system is able to adapt to workload changes by provisioning and deprovisioning resources in an autonomic manner, such that at each point in time, the available resources match the current demand as closely as possible. This implies designs that have no contention points or central bottlenecks, resulting in the ability to shard or replicate components and distribute inputs among them.

Message-driven

Reactive systems rely on asynchronous message-passing in order to ensure loose coupling among components, isolation, and location transparency. In turn, the system can be adapted easier (in order to become elastic). Another important aspect is the location transparency of components, which assumes the caller should not worry about the physical location of the target.

Conclusion

This chapter was about the theoretical aspects of the actor model, its history, and various aspects of a reactive system. While entire books can be written on some of these topics, the idea was to give some basic information and context to what this book is about.

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.