CHAPTER 2

Using Regular Expressions in .NET

The concept of regular expressions first arose in the 1950s when an American mathematician, Stephen Kleene, designed a simple algebraic system to understand how the brain can produce complex patterns. In 1968, this pattern algebra was described in the Communications of the ACM and implemented in several UNIX tools, particularly GREP, a UNIX tool for searching for files. When the Perl programming language from the late 1980s integrated regular expressions into the language, adding features to the original algebra, it brought regex parsing into the mainstream programming community.

Regex processing exists in many languages, so the patterns and rules should work fairly consistently no matter what tool you are using. There are some subtle differences we will point out as we explore examples, but most implementations support the language elements the same way.

Microsoft Regex

For purposes of this book, we are going to use the regex processing engine provided by Microsoft in the .NET framework. We will use C# as our base language, however, with minor differences; the code examples will work in VB.NET. The patterns should work in .NET, PHP, Python, etc.

The Microsoft .NET Framework since version 1.1 has supported regular expressions in the System.Text.RegularExpressions assembly. This assembly needs to be included in any application you write that wants to take advantage of regular expressions.

Regex Class

The regex class can be used to create an object that will allow you set a pattern and some options, and then apply this pattern to strings. You can search for strings, split a string to an array, or even replace strings within a text.

You can use the regex class in two ways. The first is by creating a regex object. You do this by passing a regex pattern and optionally some regex settings. However, one drawback to using this approach is that the regex pattern cannot be changed once the object has been instantiated.

You can also use the regex class as a static class (or shared in Visual Basic). When using this approach, you will need to pass both the pattern and the search string to the regex call.

Which approach to use depends on how you are using the regex. If you are reading a text file line by line, and using the same regex to split each line into words or columns, then it would be beneficial to create a regex object and let the framework compile and cache the expression. You’ll get better performance from the regex engine using this approach.

If you take a text string and apply several different regex patterns to it (such as our examples where we are searching through help messages), then using the static regex would make more sense, since each regex is used once and you don’t gain much from keeping a compiled version around.

Note: The Microsoft engine will compile regex expressions and keep them in the cache (which defaults to 15 items). If you reuse a pattern, it could already be in the cache, which helps performance. However, every time you create a regex object (rather than the static class), that regex will be recompiled and added to the cache.

Constructor

To create a regex object, you need to pass the pattern to the regex at a minimum. The basic syntax is:

string pattern = @"[0-9A-Z]"; // Pattern for hex digit Regex theRegex = new Regex(pattern); |

Tip: Regex strings often contain characters that might normally be escaped in a string literal, particularly the \ character. By preceding your regular expressions string with the symbol @, you can avoid the need to escape any characters.

You can also pass an enumerated list of regex options (separate each option with the | character). To take the above constructor code and add options to make it case insensitive, as well as process the string from right to left, we could combine the following options (we will discuss the options themselves in more detail in a later chapter):

string pattern = @"[0-9A-Z]"; // Pattern for hex digit Regex theRegex = new Regex(pattern,RegexOptions.IgnoreCase | RegexOptions.RightToLeft); |

Note: .NET 4.5 has added a third optional parameter, a TimeSpan option. By default, a regex will not time out, but rather keep searching. If you need the regex to only run for a defined period of time, you can add the timespan to the regex when the object is constructed.

Regex Options

RegexOptions is an enumerated type of the various options you can specify to control how the regex is processed. Some common options are described in Table 2:

Table 2: Common Regex Options

Option | Description |

None | No options specified, default regex processing. |

IgnoreCase | Regex patterns are normally case sensitive; this option makes the regex case insensitive. |

Multiline | Certain metacharacters ($ and ^) mean the beginning and end of a string; setting this option changes their meanings to the beginning and end of a line. |

Singleline | The dot metacharacter does not match the linefeed; using this option causes the linefeed to be matched by the dot as well. |

There are additional options which we will cover in later chapters of the book.

Regex Methods

There are both regular class methods and static methods, depending on whether you are using a created object or a static object reference. The methods are similar, the main difference being that when using the static method, you need to pass the regex pattern as a parameter.

IsMatch()

The IsMatch() method returns a Boolean value indicating whether or not the text matches the regular expression. Most often, it is used to validate that a particular string looks like the pattern, such as a credit card number, phone number, etc.

1.1.1.1.1IsMatch( string Searchtext [, int position] )

When used against a regular object, there are two parameters. The first is the string to search and the second optional parameter, which is a position within the string at which to start searching.

1.1.1.1.2IsMatch( string Searchtext, string pattern [, RegexOptions] [, TimeSpan] )

When the static method is called, the search text and regex pattern are required. The regex options (enumerated list separated by the | pipe) and a TimeSpan object are optional (.NET 4.5 onward).

string pattern = @"[0-9A-Z][0-9A-Z]"; // Pattern for hex digits Regex theRegex = new Regex(pattern); if (theRegex.IsMatch("B4") ) { // Found a hex number }; |

Typically IsMatch() is used when you need no further manipulation of the string or simply want to validate that the string looks like the type of data you are expecting.

Match()

The Match() method works very similarly to IsMatch(), except that it returns a match object rather than a Boolean value. A match object is defined by a class within the regex assembly that provides details about the match found in the string.

1.1.1.1.3Match( string Searchtext [, int position],[int NumberOfChars] )

When used against a regular object, there are three parameters. The first is the string to search. The second is an optional parameter for the position within the string at which to start searching. The third optional parameter is the number of characters to search within the string.

1.1.1.1.4Match( string Searchtext, string pattern [, RegexOptions] [, TimeSpan] )

When the static method is called, the search text and regex pattern are required. The regex options (enumerated list separated by the | pipe) and (.NET 4.5 onward), a TimeSpan object are optional.

The returned Match object contains information about the match. The key properties are:

- Success: Boolean value indicating whether the search was successful or not.

- Index: Where in the search text the match was found.

- Length: Size of the match text.

- Value: The content of the matched text.

string pattern = @"(\([2-9]|[2-9])(\d{2}|\d{2}\))(-|.|\s)?\d{3}(-|.|\s)?\d{4}"; string source = "Please call me at 610-555-1212 ASAP !"; string cPhone = "";

Match theMatch = Regex.Match(source, pattern); if (theMatch.Success) { int endindex = theMatch.Length; cPhone = source.Substring(theMatch.Index, endindex); } |

In this example, we are searching for a phone number pattern, then using the match object’s properties (i.e. Index and Length) to extract the phone number string from the larger source string. There are additional properties and methods to the Match object which we will cover in later chapters.

Matches()

The Matches() method is very similar to the Match() method, except it returns a collection of match objects (or an empty collection is no matches found).

1.1.1.1.5Matches( string Searchtext [, int position] )

When used against a regular object, there are two parameters. The first is the string to search and the second optional parameter is a position within the string to start searching at.

1.1.1.1.6Matches( string Searchtext, string pattern [, RegexOptions] [, TimeSpan] )

When the static method is called, the search text and regex pattern are required. The regex options (enumerated list separated by the | pipe) and a TimeSpan object (.NET 4.5 onward) are optional.

string pattern = @"(\([2-9]|[2-9])(\d{2}|\d{2}\))(-|.|\s)?\d{3}(-|.|\s)?\d{4}"; string source = "Please call me at home 610-555-1212 or my cell 610-867-5309 ASAP !"; string cPhone = ""; var phones = new List<string>(); foreach (Match match in Regex.Matches(source, pattern)) { int endindex = match.Length; cPhone = source.Substring(match.Index, endindex); phones.Add(phones); } |

Split()

The Split() method in the regex assembly is very similar to the Split() method in the System.string class, except that a regex pattern is used to split the string into an array of strings.

1.1.1.1.7Split( string Searchtext [, int position],[int NumberOfChars] )

When used against a regular object, there are three parameters. The first is the string to split into an array of strings, the second optional parameter is the position within the string at which to start searching. The third optional parameter is the number of characters to search within the string.

1.1.1.1.8Split( string Searchtext, string pattern [, RegexOptions] [, TimeSpan] )

When the static method is called, the search text and regex pattern are required. The regex options (enumerated list separated by the | pipe) and a TimeSpan object (.NET 4.5 onwards) are optional.

For example, you might use code similar to below to split a large text into individual sentences, and then each sentence into words.

string source = "When I try this website, the browser locks up"; Regex WordSplit = new Regex(@"[^\p{L}]*\p{Z}[^\p{L}]*";); string thePattern = @"(?<=[\.!\?])\s+"; string[] sentences = Regex.Split(source,thePattern); foreach (string sentence in sentences) { string[] Words = WordSplit.Split(sentence); } |

There are a few additional methods and properties in the regex assembly which will be introduced in later chapters.

Regex Tester Program

In order to test out some of the regex patterns in this book, we are going to create a simple Windows Forms application for testing expressions. There are also websites that provide similar functionality, such as www.regex101.com, which provides a regex tester for JavaScript, PHP, or Python. While the patterns described within this book will work with each of the various regex engines, you should use this regex application if you want to test with the .NET Regular Expression framework, or try the website if you work with a different programming environment.

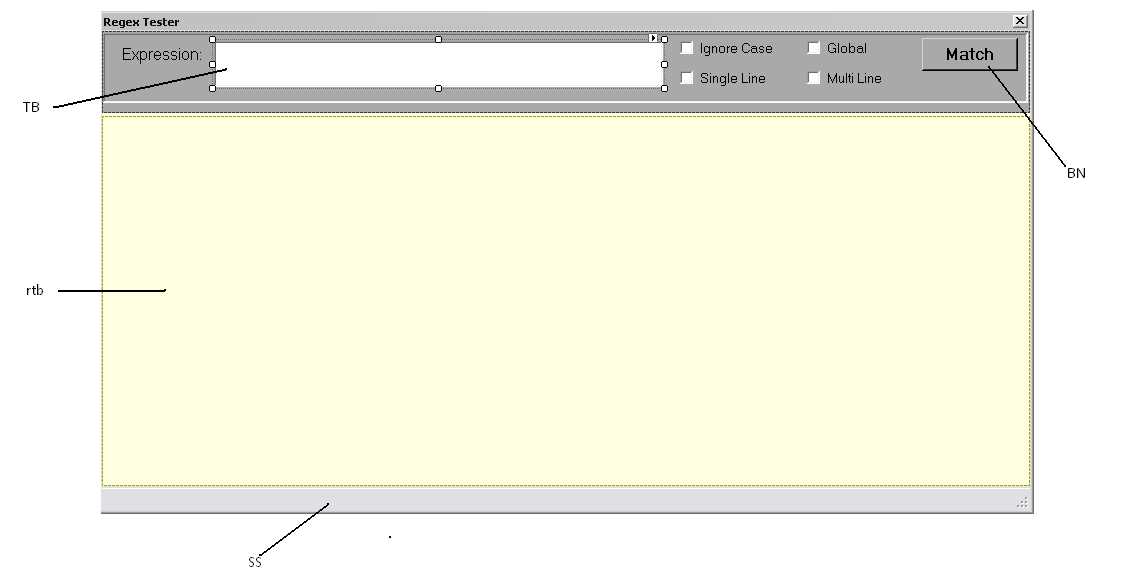

Figure 2: Regex Tester

Layout

The solution is available as part of this book; you can also create it yourself.

- Create a Windows Forms application.

- Add a Split Container.

- Set the Orientation to Horizontal.

- In the top box, add a Panel, and in the bottom box, add a Rich Text Edit box.

Figure 3: Layout

Panel

The panel at the top of the form holds the regular expression text and option boxes. You can name the controls anything, but the following references the control names in Table 3.

Table 3: Panel Control Elements

Element | Property | Value |

|---|---|---|

Textbox | Name | TB |

Font | Courier New, 9.75pt | |

Checkbox | Name | ICCB |

Text | Ignore Case | |

Checkbox | Name | GBCB |

Text | Global | |

Checkbox | Name | SLCB |

Text | Single Line | |

Checkbox | Name | MLCB |

Text | Multiline | |

Status bar | Name | SS |

Items | Add a Status label called SLAB |

Rich Edit Text Box

The Rich Edit Text Box will be used to display the input string and the search text result. The code finds all matching patterns and highlights them within the RTF edit box. Set the property name to rtb. Also set the anchors properties to top, bottom, left, and right to have the text box fill the entire lower panel.

Code

Once the form is created, add the following code (feel free to change the colors if you’d like).

public partial class MainForm : Form {

Color BGColor = SystemColors.Info; Color FGColor = Color.Navy; Color BGHighlight = Color.Turquoise; Color FGHighlight = Color.Black; public MainForm() { InitializeComponent(); rtb.BackColor = BGColor; rtb.ForeColor = FGColor; } |

Double-click the button to generate the OnClick event, and add the following code to the form to handle the event:

private void BN_Click(object sender, EventArgs e) { SLAB.Text = ""; // Reset all colors. ResetRichTextBox(); string pattern = TB.Text.Trim(); string source = rtb.Text; RegexOptions theOpts = RegexOptions.None; if (MLCB.Checked) { theOpts = theOpts | RegexOptions.Multiline; } if (SLCB.Checked) { theOpts = theOpts | RegexOptions.Singleline; } if (ICCB.Checked) { theOpts = theOpts | RegexOptions.IgnoreCase; } // If global, then iterate the Matches collection. if (GBCB.Checked) { try { foreach (Match match in Regex.Matches(source, pattern, theOpts)) { HighLightResult(match); } } catch (Exception ex) { SLAB.Text = ex.Message; } } else { try { Match theMatch = Regex.Match(source, pattern, theOpts); if (theMatch.Success) { HighLightResult(theMatch); } else { SLAB.Text = "Not found..."; } } catch (Exception ex) { SLAB.Text = ex.Message; } } } |

Then add a couple of internal functions:

private void HighLightResult(Match OneMatch) { int endindex = OneMatch.Length; rtb.Select(OneMatch.Index, endindex); rtb.SelectionBackColor = BGHighlight; rtb.SelectionColor = FGHighlight; } private void ResetRichTextBox() { rtb.SelectAll(); rtb.SelectionBackColor = BGColor; rtb.SelectionColor = FGColor; } private void TB_TextChanged(object sender, EventArgs e) { ResetRichTextBox(); } |

Feel free to customize the code elements and such, but be sure to either create the application or download it; it will be very handy as you explore the regular expressions described throughout the book.

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.